2025:412 - BUTCHERSARMS, Ballyfermot Lower, Dublin

County: Dublin

Site name: BUTCHERSARMS, Ballyfermot Lower

Sites and Monuments Record No.: N/A

Licence number: 23E0269

Author: Antoine Giacometti, Archaeology Plan

Author/Organisation Address: 129 North Strand D03 W8C1

Site type: Settlement cluster

Period/Dating: Early Medieval (AD 400-AD 1099)

ITM: E 710491m, N 733870m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.343507, -6.340690

This entry describes the results of the 2025 season of archaeological excavation at Butchersarms, Ballyfermot. In 2023 and 2024 excavation of the eastern part of the site identified the remains of a Viking camp and an early medieval non-ecclesiastical cemetery (refer entry 2024:319). The 2025 season focused on the centre-north of the site (Area G) and identified numerous features associated with the Viking camp.

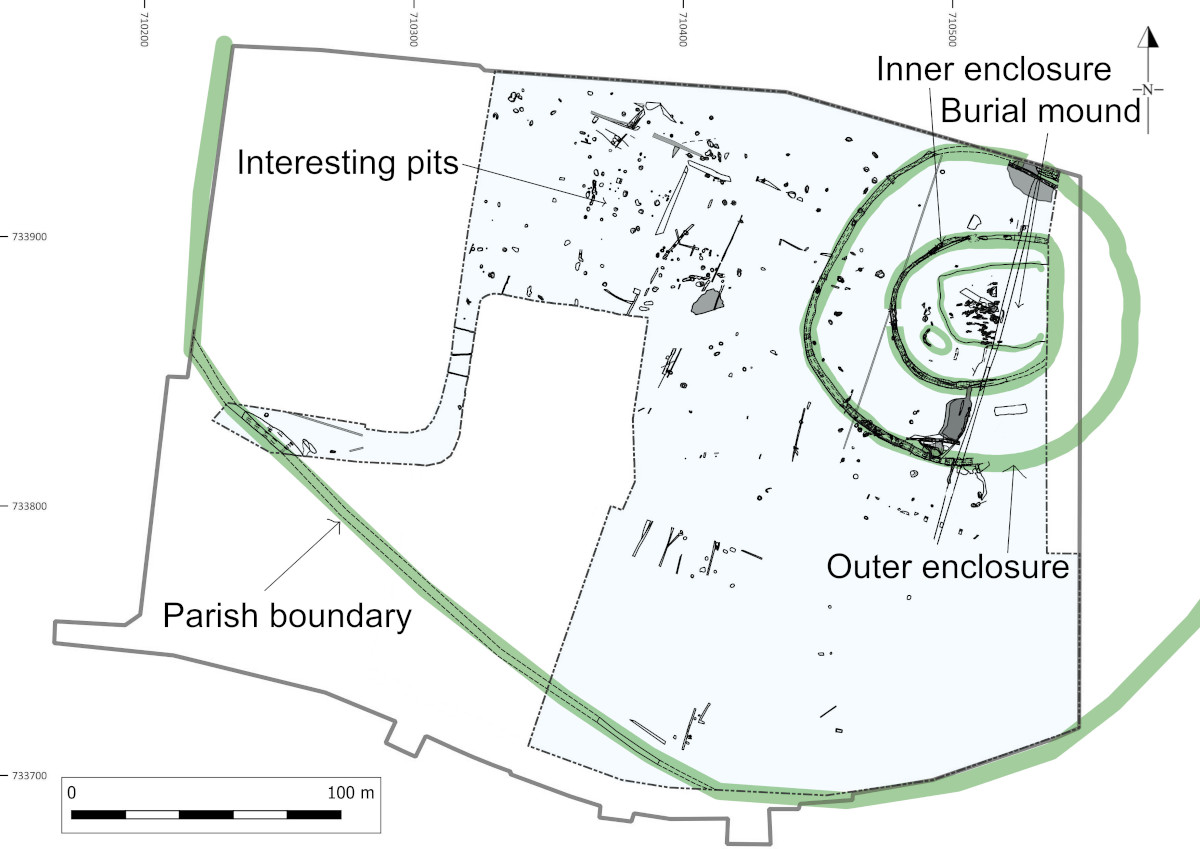

The 2025 excavation at Butchersarms reaffirmed the results of the 2023-2024 excavation (Giacometti 2025, 23E0269). The archaeological evidence from this site dates broadly to the early medieval period/first millennium AD, though Middle Bronze Age activity is also present. Two concentric enclosures 50m and 115m diameter in the eastern portion of the site contain a burial mound with c. 300 inhumations and a possible rectangular structure with rounded corners. This is in turn enclosed by a sub-circular enclosure c. 450m forming the parish boundary of Kilmainham dating to at least the late medieval period century, which encompasses many ‘interesting pits’ filled with animal bone.

The report on the 2024 findings concluded that the three concentric enclosures may represent a non-ecclesiastical cemetery/assembly site dating approximately to the fourth to ninth centuries AD, possibly pre-dating the nearby ecclesiastical site of Cell Maighnean. The 2025 excavation, however, found no evidence that the parish boundary is contemporary with the inner and outer enclosures, and it may be later (possibly Viking-era or medieval). The site was occupied by a Viking camp in the mid-ninth century and there are numerous artefacts from this phase, including the only three Northumbrian styca (coins) found on the island of Ireland, three lead weights, three complete Viking-type spearheads, keys, and decorated copper alloy objects. Of particular interest is the evidence that the pre-existing burial ground was reused by the Vikings in the ninth century for burial.

The 2025 season involved the excavation of numerous features termed ‘Interesting Pits’, which were characterised by containing very large volumes of animal bone, being spatially organised between the parish boundary and the outer enclosure, and having standardised forms. Three types (A, B and C) were noted, with type A probably intended as latrines or cesspits, and type B as wastepits. Type C, the broader shallower pits of which there were only three, may be related to crafting or washing. Given this standardisation in fills, location, form and size, all of the ‘interesting pits’ are almost certainly broadly contemporary and relate to a distinct activity.

In terms of artefacts, 1,298 objects were excavated in 2025, the vast majority from the ‘interesting pits’, with a smaller amount of artefacts deriving from the parish boundary and other pits. Finds in the interesting pits included a styca (a coin minted in York dating to the mid-late ninth century), a fragment of a silver Gratia Dei Rex coinage of Charles the Bald, struck at Le Mans (dating from 864, and common on Viking sites across Northern France and Britain), a bone comb, antler finger ring, iron fish hooks, loom weights, unidentified metal objects, decorated copper alloy ring pins, worked burnt shell, fragments of lead and horn waste, a buckle, a spearhead, and a fragment from a glass vessel of possible ninth-century date, which is certainly not of European origin and may have been manufactured in an Islamic or Eastern Mediterranean country (Ed Bourke, pers. comm. 2025). Alongside this, a very large volume of animal bone was identified from the interesting pits, including butchered large mammal bone, fish bone, shell, and complete animal skulls (often horse).

Of particular importance are the 256 fragments of ceramic crucible, and 243 ceramic moulds or lime/bone silver-ingot moulds, from two Type A ‘interesting pits’. These indicate extensive silver smithing and iron working on the site. The silver smithing evidence is very interesting as silver ingot moulds made of crushed oxidised bone and lime were identified in one of the interesting pits. These are likely to have been manufactured on site in a small hearth located within the inner enclosure, next to the burial mound. This hearth contained crushed oxidised bone. A similar feature was excavated by the author in 2021 at a cemetery settlement at Donacarney Great 2. There, a small kiln associated with a Hiberno-Norse re-occupation contained white material which looked like oxidised bone but which was (probably wrongly) identified at the time as lime. The two features are very similar and both are located in the mounds of much older cemeteries. It is therefore conceivable that in both cases the silver smith was deliberately selecting human remains for the purposes of silver craftwork.

No internal pattern was evident within and between the ‘interesting pits’. In terms of numbers, about a hundred interesting pits have been excavated across ten acres of excavation between the parish boundary and outer enclosure. Considering that the total space between the two enclosures was c. 23.5 acres, this suggests up to 235 interesting pits may originally have been located here if their distribution remains constant. Interestingly, this figure (of 10 per acre) is also the figure giving in camping guidelines as typical of a modern campsite. The absence of houses and unusually high quantity of animal bone, the interpretation of the pits as latrines and waste pits, and their standardised form and location, support the interpretation that these are the physical remains of an organised – possibly military – campsite.

Only one comparable example has been identified by the author for these ‘interesting pits’. These are from two pits excavated at the Central Hotel (C264 & C268, 22E0015, P. Duffy pers. comm. 2025). Both were assigned to the earliest phase of activity on that site and returned radiocarbon dates of 773-978 AD (2-sigma). They were sub-rectangular in form and similar in shape and size, with steep sides and flat bases, measuring c. 1.5m across, and contained a large assemblage of animal bone including fish bone. These were found near the location of the possible Viking camp at the Poddle and Black Pool (Simpson 2005, 34-48).

The parish boundary excavation attempted to identify the earliest phase of this boundary. This boundary forms a c. 400m diameter D-shaped enclosure. The boundary was marked as a Parish Boundary (of St James) on the First Edition OS map of c. 1847, and as the Parish Boundary of Kilmainham on the seventeenth-century Down Survey. The boundary also closely matches the liberty of the manor of Kilmainham, lands granted to the Hospitallers by Strongbow in c. 1174 (Frank Cullen research for Royal Irish Academy 2024, unpublished). In the event three phases of activity were identified. The latest was nineteenth-century, the middle phase was seventeenth-century, and the earliest was not dated and contained shell, charcoal, animal bone, and a broken iron knife. The earliest phase thus probably dates to between c. 400 and 1500 AD.