2020:146 - KNOCKNASHEE, Sligo

County: Sligo

Site name: KNOCKNASHEE

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SL032-013001

Licence number: 20E0415

Author: Dirk Brandherm

Author/Organisation Address: School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen's University, Belfast, BT7 1NN

Site type: Earthworks and Structure

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 555638m, N 818902m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 54.117257, -8.678535

For two weeks in August 2020 an excavation was carried out on the eastern edge of the summit plateau of Knocknashee hill, on the perimeter of the Knocknashee Archaeological Complex (SL032-013—), by a team comprising mostly local volunteers, organized by the Archonry Mullinabreena Community Enhancement Group and led by archaeologists from Queen’s University Belfast. Funding for the excavation was generously provided by Sligo County Council through its Community and Voluntary Grant Scheme.

The principal aim of the excavation was to determine the nature and the date of the main perimeter bank enclosing the plateau, and of the bank running along the edge of the terrace situated below the eastern edge of the plateau. In the specialist literature, this system of banks has generally been interpreted as part of the defences of a Bronze Age hillfort (Condit et al. 1991; Egan et al. 2005), coeval with the Late Bronze Age roundhouse occupation of the summit plateau (Brandherm et al. 2020). However, the limited surviving height of the banks (<0.7m) has always sustained doubt regarding the presumed defensive nature of these features.

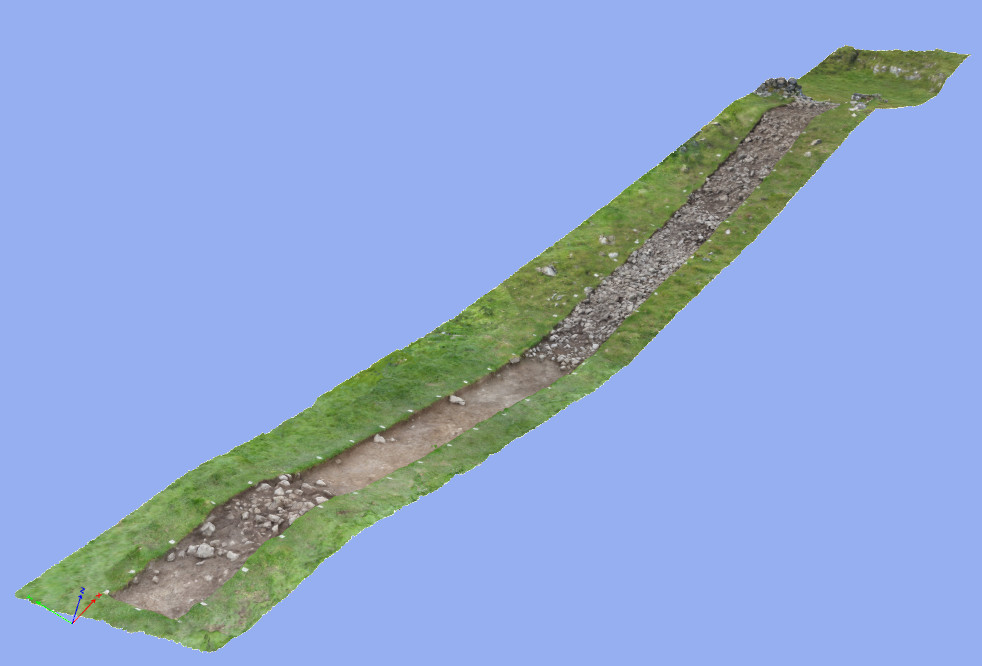

The exavation consisted in opening a 1.5m wide and 30m long trench across both banks, exposing a section through the entirety of the upper embankment and the lower terrace. A modern dry stone wall defining the townland boundary of Knocknashee Common that sat on top of the main perimeter bank had to be dismantled before a cut could be executed through that bank. In the dismantling of the wall and subsequent cutting of the bank it emerged that, surprisingly, the dry stone wall protrudes through the ‘bank’ and sits directly on decayed limestone bedrock, and that what had hitherto been perceived as an earthen bank appears to be tumble from that wall on which turf has developed.

The thin stratigraphic layer separating the topsoil from the bedrock contained both a small number of prehistoric chert implements, apparently not in their original context, and a much larger quantity of modern material, including broken glass, glazed pottery and iron fence fittings. Broken glass and a piece of aluminium foil were also found between the two lowermost tiers of the dry stone wall, for which a prehistoric date can thus be ruled out with confidence. However, it needs to be stressed that so far this stratigraphic sequence has only been established for a 1.5m wide cutting through a mile-long bank, and that further cuttings through other sections of this bank would need to be undertaken before the entire system of banks could definitely be discounted as a prehistoric feature.

On the slope separating the line of the main perimeter ‘bank’ and dry stone wall from the lower terrace, what appears to be a natural scree was uncovered. In contrast, the soil of the terrace itself contained very few stones. While the cutting through the outer bank on the downslope edge of the lower terrace did not produce any conclusive dating evidence, it did reveal its internal structure, comprising mainly large and medium-sized stones in a dark soil matrix. The lower bank is therefore tentatively interpreted as a clearance feature relating to an attempt at land improvement on the lower terrace, whose deeper soil and more sheltered position would always have made it more suitable for the growing of crops than the main summit plateau (cf. Brandherm et al. 2018).

In conclusion, the findings from this excavation do not lend support to an interpretation of the site as a Bronze Age hillfort. While a Late Bronze Age date for at least some of the roundhouse occupation of the plateau has been firmly established by previous work (Brandherm et al. 2020), on present evidence that Bronze Age occupation would seem to have been unenclosed. As indicated above, further fieldwork at the site will be needed to corroborate those findings.

References

Brandherm, D.; McSparron, C.; Kahlert, T. and Bonsall, J. 2018. ‘Topographical and geophysical survey at Knocknashee, Co. Sligo: results from the 2016 campaign.’ Emania 24, 81-96.

Brandherm, D.; McSparron, C. and Boutoille, L. 2020. ‘Excavation of Late Bronze Age roundhouses at Knocknashee, Co. Sligo: preliminary results from the 2017 campaign.’ Emania 25, 155–164.

Condit, T; Gibbons, M. and Timoney, M. 1991. ‘Hillforts in Sligo and Leitrim.’ Emania 9, 59-62.

Egan, U.; Byrne, E. and Sleeman, M. 2005 Archaeological Inventory of County Sligo, Vol. 1: South Sligo, comprising the Baronies of Corran, Coolavin, Leyny and Tirerrill. Dublin, Stationery Office.