2010:731 - CASTLEQUARTER, Wexford

County: Wexford

Site name: CASTLEQUARTER

Sites and Monuments Record No.: WX009-005

Licence number: 09E0393

Author: James Lyttleton, Department of Archaeology, Memorial University of Newfoundland

Author/Organisation Address: St John’s, NL A1C 5S7, Canada

Site type: Castle - unclassified

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 693253m, N 654570m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.634333, -6.622329

A second season of fieldwork was conducted on the site of a castle and manor house (WX009–005/008) in the townland of Castlequarter, Clohamon, Co. Wexford. This consisted of testing and sample excavation. This work is an important component of an international research project sponsored by the Royal Irish Academy, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Historic St Mary’s City, Maryland and University College Cork. The project is looking at the archaeology of early English colonial expansion in the 17th century across the North Atlantic, with particular reference to Sir George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore, whose family acquired lands in the Plantations of north Wexford and Longford, as well as established colonies in Newfoundland and Maryland through the 1620s and 1630s. In the context of the early origins of empire, the Plantations in Ireland were important as they were the first large-scale enterprises engaged upon by the Crown that could provide the necessary experience in funding, transporting and settling English colonists further afield in North America.

In this season (2010), it was decided to examine the castle site again in order to learn more about the development of Clohamon Castle through the late medieval and post-medieval periods. Trench 4 was opened to more fully examine the castle’s defensive perimeter. Inspection of aerial photography taken in the 1980s, when the site was not covered by dense vegetation, suggests that a significant proportion of the rock outcrop, on which the castle site is located, was not impacted upon by quarrying activities. Accordingly Trenches 6 to 12 were opened to ascertain if further evidence of the castle complex remained on the rock outcrop, outside the areas affected by such quarrying. Due to dense vegetation, as well as the extensive spread of quarry debris in the area, Trenches 6 to 12 were opened by a mechanical digger using a 1.5m-wide toothless bucket.

In the field to the north of the castle site, geophysical survey (magnetometry) in the 2009 season indicated a series of anomalies including a couple of linear boundaries that were marked on the first-edition OS map. Also in the previous season, test-pitting of the ploughsoil in the area recovered ceramics and tobacco-pipe fragments that were typical of the 17th century. For the 2010 season it was decided to open three 2m x 2m cuttings to ground truth the results of these findings—Trenches 14–16. In order to allow for a meaningful record of exposed archaeological features, Trench 15 was expanded to 3m x 4m and Trench 16 was expanded to 3m x 3m.

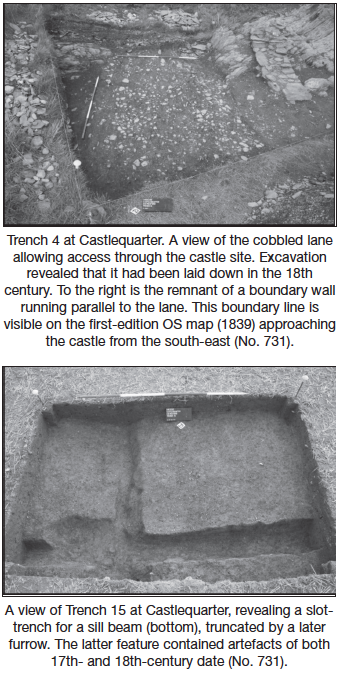

Excavation of Trench 4 unearthed much weathered scree that formed after the collapse or robbing of the castle wall. Removal of this scree uncovered a roughly coursed shale wall, up to three courses in height, bonded with a silty gravelly fine sand. This wall may be the remains of the boundary wall depicted on the first-edition OS map (1839), approaching the castle site from the south-east. A small ditch served as another field boundary, this time orientated in the opposite direction, approaching from the north-east. A stone wall may have followed alongside this ditch, which at some stage collapsed as fill into the ditch itself. A cobbled laneway, orientated north-north-west/south-south-east, was laid down sometime in the 18th century. A large flag-filled drain was placed along its eastern side. Removal of this laneway uncovered medieval deposits of sands and silts, some of which yielded sherds of Leinster cooking ware. These deposits filled a rock-cut ditch, measuring 2.96m in length, 2.2m in width and 0.9m in depth. This ditch, orientated east–west, is a continuation of the shallow external castle fosse uncovered in the 2009 season (Excavations 2009, No. 842). There was no indication whatsoever that a causeway crossed the fosse in this area, as was suggested after last season’s excavation. However, this ditch appears to have turned direction as indicated by the possible traces of another rock-cut ditch extending to the north, measuring in width from 1.9m at base to 3.75m at top and 0.97m in depth. It is noteworthy that the 18th-century cobbled laneway was placed exactly in line over this possible ditch. It is now thought that the castle wall investigated the previous year represents the original tower-house, with the rock-cut ditch defining the easternmost corner of the castle site.

The next cutting, Trench 6, was opened to ascertain if the castle defences extended to the edge of the river terrace on which the castle site is situated. Excavation of this trench only revealed natural subsoils, with no indication of perimeter castle walling or external fosse. Trenches 7–12 were opened to ascertain if further evidence of the castle complex remained on the rock outcrop, on the other side of the quarry, opposite to where castle remains have been uncovered. Excavation of Trenches 7–10 revealed that a significant amount of quarry debris (up to 2.5m in depth) had been deposited over the surface of the rock outcrop. Unfortunately, no features or artefacts of archaeological significance were uncovered in these trenches. Excavation of Trench 11 revealed an expanse of shale bedrock, the undulations of which were filled with natural subsoils, with the exception of one. This appears to have been a deliberately cut cleft in the bedrock that was backfilled. It also contained a post-hole that was burnt in situ. Among a small number of artefacts recovered from the topsoil was a possible sherd of late 17th-century Buckley ware. There appears to have been limited soil development above the bedrock in this particular location, which may preclude the survival or indeed presence of archaeological deposits. No other post-holes or archaeological features were uncovered. Excavation of Trench 12 revealed a series of garden furrows which, on examination, proved to be shallow cuts with slightly rounded bases. No artefactual material was recovered from the fills. According to local information, gardening was carried out in this area in the mid-20th century.

In the field to the north of the castle site, geophysical survey (magnetometry) in the 2009 season indicated a series of anomalies including a couple of linear boundaries that were marked on the first-edition OS map. Test-pitting of the ploughsoil in the area recovered ceramics and tobacco-pipe fragments that were typical of the 17th century. A 2m by 2m cutting, Trench 14, was opened over one of the linear anomalies and a boundary ditch was uncovered. It appears that the ditch quickly filled in with sandy silts and clays as there is no evidence for silting at the base. It also is possible that bank material was pushed across the filled ditch. The only datable artefact recovered from the ditch was a tobacco-pipe stem in one of the upper fills with a bore size typical of the 17th century. In a 1660 lease signed between the second Lord Baltimore and a syndicate of merchants, the enclosure of the surrounding farmland is referred to and it may be the case that many of the field boundaries in the vicinity of Clohamon today were laid out at that time, including the example uncovered in Trench 14.

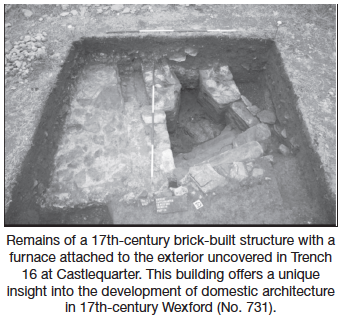

Trench 15 revealed a slot-trench for a sill beam. The lower fill yielded a 17th-century farthing token, issued under royal licence between 1613 and 1644. Interestingly, this structural feature ran parallel to the aforementioned field ditch uncovered in Trench 14, suggesting that the timber structure and boundary may be contemporary. The slot-trench uncovered may represent a rare survival of a timber-framed building. Documentary and cartographic sources for the Ulster Plantation suggest that timber-framed houses were common in areas where woodland was commonplace. As Clohamon was located in an area where there were also extensive oak forests, it is likely that English-style timber-framed buildings were erected by planters in the area. However, there is also a Gaelic-Irish timber building tradition to be cognisant of, as evidenced in a c. 1610 account of an Irish ‘great hall’ in an adjacent parish to the south of Clohamon. The slot-trench was truncated at a later stage by a furrow with a rather irregular profile. The fill of this furrow contained a variety of 17th- and 18th-century artefacts.

Trench 16 uncovered the remains of a brick-built building of 17th-century date with an attached furnace. As exposed in the trench, the brick structure measures 2.25m by 1.23m externally. The brick wall, bonded with a lime-based mortar, survives to two courses in height with the bricks laid in English bond; i.e. a row of headers followed by a row of stretchers. The interior was covered with shale flagstones heavily bonded with a lime-based mortar. This structure probably served as a bake house for the occupants of the manor house and/or village. Many household inventories of the period record the presence of ancillary buildings such as washhouses, dairy houses and brew houses. The same 1660 lease of Clohamon indicates that there were a number of outbuildings associated with the manor house. The bakehouse uncovered this season is a unique survival of such a building, as low status buildings, whether in the grounds of manor houses or elsewhere, rarely survive.

The archaeological fieldwork to date has yielded a valuable insight into the industrial and architectural development of Clohamon under the stewardship of Lord Baltimore and provides the artefactual and architectural evidence necessary for a comparative study of Lord Baltimore’s colonial endeavours in Ireland and North America.