2004:1930 - LISNAKILL, CO. WATERFORD, Waterford

County: Waterford

Site name: LISNAKILL, CO. WATERFORD

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR WA017-122

Licence number: 04E829

Author: MARY CAHILL AND MAEVE SIKORA

Author/Organisation Address: —

Site type: Early Bronze Age graves

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 654134m, N 607946m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.220608, -7.207712

Introduction

In May 2004 a short cist containing a cremation and a vessel was discovered in the garden of a dwelling house at Lisnakill, Co. Waterford. The capstone was discovered at a depth of c. 0.2m by the owner, Mr Billy O’Keefe, when he was gardening. Thinking it was a natural rock, Mr O’Keefe tried to break up the stone with a sledgehammer. After breaking a small portion of the rock, the cist containing the bone and vessel became visible underneath. The discovery was reported to the NMI and an initial site visit was carried out by Mary Cahill. The site was excavated on 14 and 15 June 2004 by Mary Cahill and Maeve Sikora.

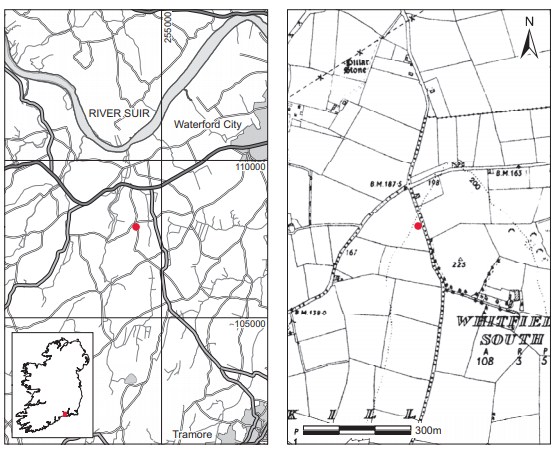

Location (Fig. 3.168)

The site was in the townland of Lisnakill, east Co. Waterford.308 It was approximately 5km south-west of Waterford city off the main Waterford to Cork road. The cist was at an altitude of 50–60m above sea level on a west-facing slope affording extensive views to the west and north. An eighteenth-century account records the discovery of a cist containing a pottery vessel and a gold armlet in the vicinity of Lisnakill (Herity 1969, 10–11; Needham 2000, 38–9).

Description of site

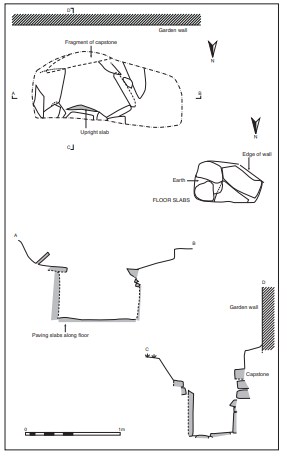

The cist was polygonal in plan, with the longer axis aligned east/west. Internally it measured 0.83m long by 0.42m wide by c. 0.49m high (Fig. 3.169). It was five-sided and formed of both upright slabs and some stone coursing. The northern side and the western and eastern ends were formed of flat slabs set upright, while the southern side was formed of a number of low uprights at the cist floor, over which were at least four courses of smaller stones. The floor of the cist was paved with five slabs, with a number of smaller slabs filling the interstices. The slabs were lifted to reveal a compacted earthen base. The cist was covered with a single slab, which was of very rotten shale. It measured approximately 0.96m long by 0.74m wide by 0.12m thick and had to be removed in fragments owing to its size. A small portion was left in situ where it ran towards the garden wall and under heavy garden shrubbery.

The cist contained the cremated remains of two adults (04E829:2), one of whom was identifiable as male, and an anomalous vase. The vessel was removed by Mr O’Keefe but had been found upright in the eastern end of the cist. The cremation deposit had been left in situ. Apart from a small amount of earth that had fallen into the cist upon discovery, the cremation was not covered by a layer of earth in antiquity.

It had been spread over the entire floor of the cist, apparently directly on the paving slabs. A small amount of bone had fallen though the paving slabs.

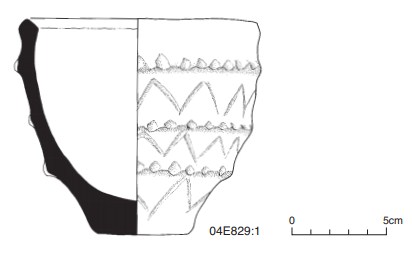

Anomalous vase, 04E829:1 (Fig. 3.170)

This small vessel is complete but has lost some of its outer surface through erosion. It has a slightly rounded external rim. There are three raised ribs on the body, dividing the vessel into four zones. The profile resembles bucket-shaped vessels but with a sharp angle in the lowest zone, resulting in a very small base. The ribs are quite prominent. Each has been divided into small sections by shallow depressions that follow the circumference of the pot. The panels between the ribs are decorated by very lightly incised slanted lines forming running V-shapes. The base is plain.

Dimensions: H 11cm; ext. D rim 12.67cm; int. D rim 10.67; D base 5.3cm.

Comment

A sample of bone from the main deposit was submitted for radiocarbon dating and yielded a result of 3660±40 BP, which calibrates to 2190–1920 BC.309 The vessel from this cist is difficult to place, as it has elements of a ribbed bowl with an unusual decorative pattern which is similar in some respects to a bipartite vase from Blanchfieldsbog, Co. Kilkenny (Ó Ríordáin and Waddell 1993, 267, no. 534). Alison Sheridan (pers. comm.) has suggested that this vessel is similar to some ridged vases from the British series.

Also recorded from Lisnakill is an important, but now lost, eighteenth-century discovery of another early Bronze Age burial. This produced an urn which contained bones, ashes and an embossed gold armlet of a type that belongs to a specialised group of gold armlets. The type is otherwise confined to Britain and, within Britain, has not been recorded north of a line that runs approximately from Flintshire in Wales to Lincolnshire on the east coast of England. It may be regarded as an exotic import into Ireland (Needham 2000, 37–8). This burial is one of the richest early Bronze Age burials ever recorded from Ireland. As its precise location within the townland is not known, it cannot be linked to the recent discovery at Lisnakill, but there remains the possibility that both sites are connected.

HUMAN REMAINS

LAUREEN BUCKLEY

Description of cremation

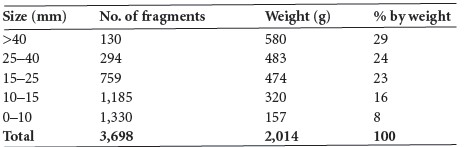

The bone was creamy brown in colour, probably owing to the surrounding soil. It appears to have been efficiently cremated, with only a few of the very small fragments being blue in colour, indicating less efficient cremation. Most of the larger fragments had a chalky texture. The bone was warped and there were numerous horizontal fissures. A total of 3,698 fragments of bone were collected, weighing 2,014g. The weight of a full adult cremation can vary from 1,600g to 3,600g (McKinley 1989), although in practice it is rare to find more than 1,500g in a single cremation.

The size and fragmentation of the bone is shown in Table 3.102, with the largest fragment being 120mm in length.

Table 3.102—Fragmentation of bone, 04E829:2.

It can be seen that there was a low proportion of small fragments less than 10mm in length, and a high proportion, more than 50% of the sample, of larger fragments more than 25mm in length. This strongly suggests that the bone was not deliberately crushed and that efforts were made to keep the bones intact when they were being collected from the pyre and deposited in the cist.

Identifiable bone

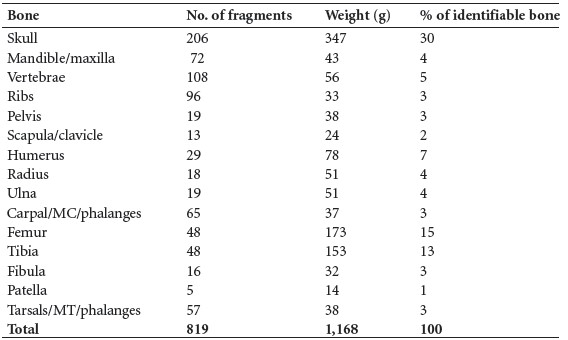

It was possible to identify 1,168g (58%) of the sample. This high percentage is due to the larger bone fragments, but it is normal to get a similar or higher percentage of identifiable bone in Bronze Age cremations of this nature. The quantity of the various bones identified is shown in Table 3.103.

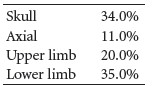

Table 3.104 summarises the percentage of various body parts identified. The proportion of skull recovered was 34%, which was almost twice what was expected. Although in theory the proportion of identifiable bone for the various parts of the skeleton should remain the same no matter how many individuals are present, in practice, since the skull is the most easily identifiable bone, if more than one individual is present the proportion of recovered skull can be considerably higher than expected. Since the proportion of skull was double what it should be, it was not surprising to discover that two individuals were present in this cremation.

The proportion of axial skeleton at 11% was half what should be expected. Since the proportion of skull was double that expected, this has the effect of decreasing the proportions of the other skeletal elements slightly. It seems that skull was collected at the expense of the axial skeleton. In addition, the vertebrae and ribs are very fragile, especially when burnt, and are not always fully recovered from the pyre. The proportions of upper and lower limb bones were very close to what would be expected from a normal cremation.

Table 3.103—Proportion of identified bone, 04E829:2.

Table 3.104—Summary of identified bone, 04E829:2.

Description of skeletal elements

Skull

A large fragment of the occipital bone, with most of the right lambdoid suture, lambda and the medial half of the right lambdoid suture visible, was present. The nuchal crest and external occipital protuberance were also present and they were strongly of the male type. There were large fragments of parietal and squamous frontal bone. Some of the bone was split through the diploe but most of the larger fragments were not.

Two left and two right orbital rims were present. One of the right and one of the left orbital rims were obviously of the male type, and there was at least one supraorbital ridge that was also of the male type. The other right and the left orbital rim were smaller, but it is not certain that they were from a female as they could have been from a smaller male. Also present from the frontal bone were two fragments with the frontal crest and part of the frontal sinuses visible. There were two left and two right petrous portions of the temporal bones. The mastoid areas of a left and right temporal bone were also present and they were also from a large male. One other right mastoid area was present, and there were two left and two right temporal fossae and two zygomatic arches. Two greater wings of sphenoid were present, and part of two right and one left zygomatic bones also survived.

A large section of the right side of the mandible and two mandibular condyles were present. There was also the anterior part and some smaller fragments of a second mandible.

Most of the left side of a maxilla was present, as well as the orbital part of the right side and some small fragments.

Dentition

Sockets for the following teeth were observed:

There were nineteen tooth roots present from a minimum of fourteen teeth and there were a few shattered tooth crowns. Most of the teeth seemed to be upper and lower molars and premolars.

Vertebrae

Fragments from at least seven lower cervical vertebrae, including the vertebral bodies and some of the articular surfaces, were present. Some of the vertebral bodies appeared to be larger than others, and the larger bodies had evidence of degenerative joint disease, with osteophytosis and porosity of the articular surfaces of the vertebral bodies evident. The right side of an axis vertebra was also present. Most of the bodies of thoracic vertebrae were present and there were at least three lumbar bodies. There were also several fragmented arches and a number of disarticulated posterior articular surfaces. At least one sacral vertebra remained.

Ribs

Several fragments of shaft, including some from near the neck area, remained. There were at least nine ribs from the left side and eight from the right side. There were also several smaller fragments of shaft that had split through the bone.

Pelvis

The pelvis was very fragmented, but there was a large fragment of left ilium from around the sciatic notch area. Unfortunately the sciatic notch was not complete. There was also a fragment of acetabulum and of the auricular surface. Fragments of iliac crest and a part of one ischium were present.

Clavicles

The lateral end of a clavicle was present, as well as a few other fragments of shaft.

Scapulae

Part of the body of a right scapula, including the lateral border and part of the glenoid fossa, was present. There were also two left and one right acromial spines.

Humerus

There were several fragments of shaft from the proximal and distal halves, as well as two fragments of proximal joint surfaces and a left virtually complete distal joint surface.

Radius

There were large fragments of shaft and a number of smaller fragments. There was a fragment of distal joint surface and two proximal joint surfaces.

Ulnae

The fragments were mainly from the proximal and distal halves of the shafts, representing at least four bones. There were two distal joint ends and two fragments of proximal joint surface, including one from a right bone.

Carpals/metacarpals/phalanges

Several carpal bones were present, including a right scaphoid, a right lunate, right hamate, right capitate, left triquetral and a trapezium. There were also eighteen metacarpal shafts, including two first metacarpals. There were eleven proximal, six middle and eleven distal hand phalanges.

Femur

The fragments were mostly all fragments of shaft, including fragments from the proximal and distal ends. There was a proximal joint surface and at least two distal joint surfaces. The shaft fragments were thick, from an adult bone with a well-defined linea aspera.

Tibiae

Several large fragments of shaft were present, including three fragments from the proximal posterior surface with the nutrient foramen present. This indicates that there were at least three tibiae present. The anterior tubercles from a left and a right bone were present. A distal joint surface and fragments of proximal joint surface also remained.

Fibulae

There were several fragments of shaft and three fragments of distal joint surfaces, including a complete right distal joint surface.

Patellae

An almost complete left patella was present. There was part of another left patella and a few other fragments of joint surface.

Tarsals/metatarsals/phalanges

Fragments of two tali, one calcaneum, a navicular and a cuneiform all survived from the tarsal bones. Two first metatarsals, a left fifth metatarsal and nine other metatarsals were present, and there were ten proximal foot phalanges and one sesamoid bone.

Minimum number of individuals

As there was duplication of many of the skeletal features of the skull and more than two tibiae and ulnae present, as well as more than the number of metacarpals, metatarsals and hand and foot phalanges necessary for one individual, it is apparent that two individuals are represented here. The amount of bone recovered was also much higher than is normally found in a single adult cremation. Both of the individuals were adult and one was a male, but it was not possible to determine the sex of the other individual.

Summary and conclusions

The cremated bone from this cist represents the remains of two adults, at least one of whom was male. Cremation had been efficiently carried out and the remains carefully collected from the funeral pyre, as all skeletal elements were present. There was slightly less bone than expected from the axial skeleton, however, and this may be due to poor collection of the ribs and vertebrae from the pyre, or it may be because they are so fragile that they did not survive in large enough fragments to be identified. Most of the fragments recovered were very large, suggesting that no ritual crushing of the bones was carried out at the time of interment.

308. Parish of Lisnakill, barony of Middlethird. SMR WA017-122——. IGR 254196 107892.

309. GrA-27919.