County: Waterford Site name: BALLYNAMUCK CAVES (1 AND 2)

Sites and Monuments Record No.: N/A Licence number: 04E0573

Author: Cóilín Ó Drisceoil and Richard Jennings

Site type: Cave

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 624948m, N 594404m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.100987, -7.635842

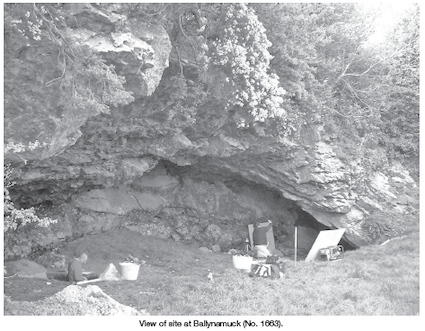

In April 2004 test-excavations were carried out at two caves near Dungarvan, Co. Waterford. The excavations formed part of research for the Dungarvan Valley Caves Project, whose primary aim is to contribute to the issue of the absence of humans from Ireland in the Late Pleistocene period. The Dungarvan valley is an area that is of great significance for the understanding of Ice Age Ireland, not least because it has produced Late Pleistocene faunal remains from four caves: Ballynameelagh, Ballynamintra and Kilgreany and a major assemblage from Shandon cave (Woodman et al. 1997). Regrettably, all of these sites have been heavily disturbed and are now unlikely to contain intact quaternary deposits. Accordingly, the project set about locating potential Late Pleistocene cave deposits at sites not previously investigated. Following fieldwork, two new caves in Ballynamuck townland, some 500m west of Shandon cave, were discovered and test excavated.

Ballynamuck 1: 'Badhbh's Hole'

This cave was first recorded by Adams et al. (1881) as 'Shandon [No. 5]—opened in the cutting for the Dungarvan and Lismore railway. Have still to be explored.' It is not clear how much of the cave has been removed by quarrying and the early maps of the area are unhelpful in this regard. What survives is an exposed quarried rock face with a large undercut feature that was once the interior wall of a large phreatic chamber (at least 15m long and 5m high). It is clear, however, that the vast majority of the chamber survives intact. Within it, two avens descend from the upper rear wall. To the right is a crawl that leads into a short series of phreatic passages measuring 45m in length. These contain, in places, sediment to within 0.3m of the roof. There is no recorded evidence that the cave was explored until 1988, when a speleologist from the University of Wales (Newport) visited and described it (Ryder 1989, 37–8). Local tradition holds that the cave is called the 'Badhbh's Hole', badhbh being the local expression for the 'banshee'. Two test-trenches were excavated at Ballynamuck 1, both within the partially quarried chamber of the cave.

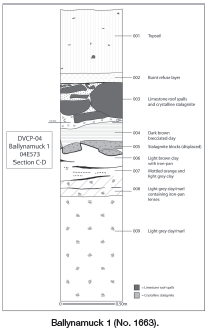

In Trench 2 three distinct sedimentary facies were recognised. Sterile laminated clay totalling 1.46m in depth (not bottomed) underlay a thick (0.7m) sterile crystalline stalagmite and roof-spall floor, which in turn underlay modern quarry debris and dumped material to a depth of 0.69m.

Deep laminated clay deposits such as those recorded at Badhbh's Hole are a relatively common occurrence in Irish caves and it is likely that the majority of these began to be emplaced after the LGM (Last Glacial Maximum, 22000–18000 BP) through low energy shallow surface wash, rill flow and transportation through fissures in the cave roof. What are somewhat less common are thick stalagmitic floors sealing deep clays. Only two sites—Shandon Cave and Foley Cave—have produced dated sequences like this and both stalagmite-sealed clays pre-date the LGM.

Trench 1 succeeded in locating the uppermost stalagmitic floor recorded in Trench 2. This is of some significance, as it indicates that, when the quarrying opened the chamber of the cave, the floor was of stalagmite (there is no good reason why deposits that may have been overlying the stalagmite would have been removed). Also, the floor is believed to be equivalent to the stalagmitic floor that sealed the deep clay deposits of potential Pleistocene age in Trench 2. It is probable therefore that there is at least some 12m by 10m of (horizontal) sediment within the chamber of Ballynamuck 1.

Ballynamuck 2

This cave was first noted by Adams et al. (1881) and listed as 'No. 6 Ballynamuck—unexplored'. The speleologist, Ryder, also investigated it in 1988 (Ryder 1989, 37). The cave has an entrance in an old quarry face that faces the Colligan estuary. It is unclear how much of the original cave was quarried.

The cave is of phreatic origin and is now fossil, development only occurring through seepages. At present a 1.5m-high by 2m-wide entrance passage angles right into a crawl 0.5m high and opens into a small chamber. The passage then continues to the right towards the quarry face before returning to the left to end in another small chamber with impenetrable tubes. The total length is c. 15m. Sediment fills the cave to within 0.2m of the roof in places.

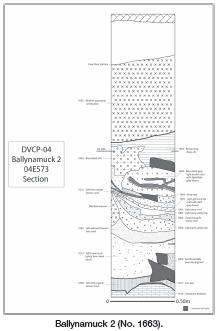

At Ballynamuck 2 three distinct sedimentary facies were noted. There was a 0.16m-deep organic silt at the base of the cave underneath 1.13m of fine sands, clays and silts, which overlay 0.6m of quarry debris intermixed with clay silt, including a shattered stalagmitic floor. A small quantity of as yet unidentified fauna was recovered from throughout the sequence.

The stratigraphy recorded at Ballynamuck 2 differed markedly from that of Ballynamuck 1. This is surprising, given the fact that sediments within the two caves are not far apart and are roughly at the same height above sea level (c. 6–7.5m OD). It appears that the Ballynamuck 2 stratigraphy is more consistent with low-energy glaciofluvial sedimentation that was emplaced by meltwater at either the end of the LGM or the Nahangan stadial. The organic-rich silt at the base of the sequence is thus likely to be either Middle Midlandian or Late Glacial in age, though the possibility that it was emplaced during a warm episode at the LGM should not be dismissed. Given the relatively low height above sea level (c. 7m OD) of the cave and the inclusion of sands within the middle facies, a glaciomarine or loess element within the sediments is feasible.

Preliminary analysis of the sediments indicates that they comprise a high percentage of allogenic material and therefore the deposits and water that emplaced them originated outside the cave. The trending of the deposits from south to north would imply that their input point was from the south (interior) of the cave and perhaps an original entrance was to be found in this direction rather than where the current quarried entrance is situated. These suppositions will require lithostratigraphical analysis and dating before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

Remarks

The Dungarvan Valley Caves Project set out to discover new Late Pleistocene cave sites that could aid in contributing to the key questions of the project. Preliminary investigations at Ballynamuck 1 and 2 have succeeded in revealing stratigraphic sequences that are potentially of late Pleistocene age. Before any further excavations at the Ballynamuck caves are carried out it is important that the exposed lithostratigraphy be fully understood and dated. Funding for this has been granted by the Heritage Council Archaeology grants scheme 2005.

References

Adams, A.L., Kinihan, G.H. and Ussher, R.J. 1881 Explorations in the bone cave of Ballynamintra, near Cappagh, Co. Waterford. Scientific Transactions of the Royal Dublin Society 1, 177–226.

Ryder, P.F. 1989 Caves in County Waterford Easter 1988. Irish Speleology 13, 37–43.

Woodman, P.C., McCarthy, M. and Monaghan, N. 1997 The Irish quaternary fauna project. Quaternary Science Reviews 16, 129–59.

Threecastles, Kilkenny