2003:1943 - WATERFORD HARBOUR: Duncannon Bar, Waterford

County: Waterford

Site name: WATERFORD HARBOUR: Duncannon Bar

Sites and Monuments Record No.: N/A

Licence number: 03E0827

Author: Connie Kelleher, Underwater Archaeology Unit

Author/Organisation Address: Department of the Environment, Heritage & Local Government, Dún Scéine, Harcourt Lane, Dublin

Site type: Wreck

Period/Dating: Post Medieval (AD 1600-AD 1750)

ITM: E 659453m, N 612019m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.256667, -7.129167

The Underwater Archaeology Unit (UAU) of the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government (DEHLG) undertook a detailed survey and discrete investigation of the shipwreck site in the summer of 2003 both before and after dredging of the navigation channel by Waterford Port. The dual aim of the project was to gain further information as to the nature, extent and potential identity of the shipwreck and to assist in the formulation of a definitive long-term management strategy for the site.

The possibility that a shipwreck on Duncannon Bar had been impacted upon was first recognised in 1999 during the harbour dredgings, when ships’ timbers were recovered from the western slope of the navigation channel. An exclusion zone was imposed and, over the following years, the DEHLG requested monitoring of dredging activity in Waterford Harbour (Niall Brady, Excavations 2000, No. 1009, 00E0949, and Excavations 2001, No. 1259, 01E0363).

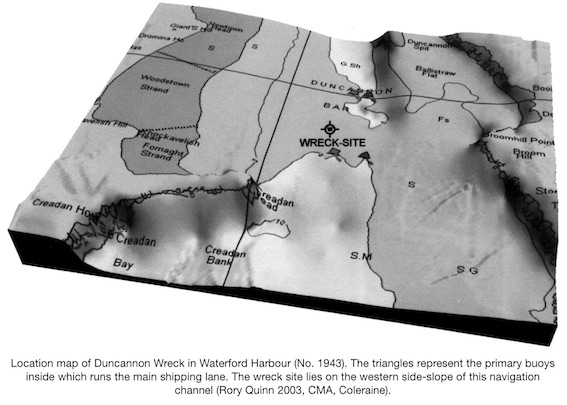

As presently known, the site extends for some 35m and is orientated north-north-west/south-south-east. It lies on the side-slope of the main navigation channel, within the dredge channel proper, at a depth of 8m at high water. The site is exposed then covers over again with sand and silt during the course of the year, due to the combined influences of the weather, tides, shipping and dredging activity. The site can be divided into two main areas: the main line of guns that run north-south and an area of exposed timbers and lead objects to the north-west of the line of guns.

Geophysical survey of the site was undertaken by the UAU and a sub-bottom profile survey was undertaken by Dr Rory Quinn of the Geophysics Department in the Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the University of Ulster, Coleraine. Both produced exciting data, with the sub-bottom survey results showing extensive buried remains, suggesting that a substantial part of the hull structure survives largely intact. The survey results further suggest that the preservation potential for archaeological remains in the non-disturbed levels is extremely high and this is borne out by the superb quality of the timbers and artefacts that have already been retrieved.

A detailed survey of the cannons was undertaken. All six recorded were iron and had their muzzles buried, which prevented exact calculation of their size. However, details from the buttons and cascabels, breech, first reinforcement rings and trunnions pointed decidedly to them dating to post-1636 and pre-1670 and belonging to the Brown Family Foundry of Britain (Robin Leigh and Charles Trollop, pers. comm.). All bar one stand in a vertical position with their breech ends facing upwards. They are of differing sizes, with three of the guns being similar and large in size. A smaller gun lies horizontally and partially buried on the seabed. Lead, in the form of both concretion and stripping, was also evident around a number of the cannon, with one gun being more or less encased by it.

The area of exposed planking to the north-west proved to be very interesting, as the timbers appear to be either outer planking or inner decking with subcircular lead objects set into them. The timber is oak with two substantial cross-timbers, not unlike structural beam timbers, at right angles to the area of planking. Some of the silt overburden was excavated to reveal one of the four lead objects and expose it further. This resulted in determining that the planking was finely cut to shape around the lead objects, which were tightly fitted into the wood. The lead object itself proved to be far more intriguing when excavated. It has a lip on the top that measures 0.6mm in width and this has a series of evenly spaced rivet holes, where it overlapped to make a seal. There is an obvious crease in the lead where it had been joined together to take circular form. As excavation progressed, it became clear that the lead object was not a bowl but continued into the seabed and was excavated internally to a depth of 0.5m, with no end in sight.

Inspection at the southern end of the line of cannon provided worrying evidence of the power of dredgers, with both the exposed hull timbers and upright cannon showing extensive impact damage. The timbers were literally chewed, with the dredge impact tearing through the substantial oak ribs and outer planking. The gun has lost its button from the cascabel and the teeth marks from the dredge head are clearly visible. The seabed here is also markedly different from the rest of the site, being much softer, looser and more unstable.

The 40m exclusion zone was adhered to during the 2003 dredgings by Waterford Port. This was monitored by the writer and subsequent survey of the wreck by the UAU showed that a significant amount of fine, loose silt had been deposited over the wreck site, but this was easily removed. In situ wood samples were taken for dendrochronological dating, but these did not produce enough rings for a positive date to be ascertained (N. Nayling, pers. comm.). An interesting date was obtained, however, from one of the timbers recovered during monitoring of the dredgings in 2003. Several ship timbers were recovered which are not believed to come from the Duncannon wreck. One of these timbers provided a dendro date of AD 1546, leaving the question open as to whether we are looking at another wreck site in that area from the Tudor period.

From the findings to date, a number of possible conclusions can be drawn and scenarios put forward to explain the nature and wrecking process of the site. The linear nature of the guns suggests that they may be in situ, possibly within their gun ports but having been pushed upwards as the wreck became more firmly embedded in the seabed. This theory gains further support from the possible outer hull planking being visible and the cannon there located vertically beside it. The smaller cannon, which is the only gun recorded to date lying in a horizontal position, may have originally stood on the deck above and collapsed downwards over time. To the north-west, the position of the lead objects also suggests that we are viewing in situ wreckage, with their length and shape possibly indicating that they may be part of the main pump system or may be scuppers (drainage holes). However, the grouping of four together, and their diameter, would militate against this theory. Another possible scenario is that they are pissdales or ‘seats of ease’ (toilets). The latter theory is supported by the extensive planking that is cut neatly to house the lead objects and the fact that there is more than one together. Pissdales were located at the ‘head’ of the ship and overhung the bow section, with the pissdale penetrating through the head and opening to the sea below. This would provide us with an orientation for the wreck, with the bow at the north-north-west and the impact area to the south-east being towards the stern. This would also suggest that this is part of the upper deck level and would tie in with the results of the sub-bottom profile survey, which shows a substantial amount of hull structure still remaining buried.

The Shipwreck Inventory of Ireland being compiled by the UAU lists over 100 wrecks for the general harbour area, with half a dozen of these dating to the 17th century. A prime candidate for the identity of the wreck is that of HMS Great Lewis, wrecked in 1645. This was a flagship of the Parliamentary navy that arrived in Waterford from Milford with three other ships to provision and relieve the Parliamentary forces in Duncannon Fort in Co. Wexford. The night before, however, the fort had been besieged by Irish Confederate forces loyal to the Royalist cause. Records recount that the Great Lewis moored below the fort, out of range of gunfire, and a number of sailors and supplies were landed. At first light, the Irish Confederates fired at the ships and three managed to cut their cables and get away. The Great Lewis, however, was caught in an unfavourable tide and wind and was prevented from moving off. It was caught under heavy mortar fire, the masts broke and the ship drifted out of range but was so seriously damaged that it sank. Most of the crew were lost. The location of the shipwreck in Waterford Harbour, about a mile south-west of Duncannon Fort, would be a likely location for the Great Lewis to have ended up. If the ship had drifted out of range but sank shortly afterwards, as sources record, there is a good chance that, without masts or cables to provide direction or control, she would have grounded on Duncannon Bar. The positive dating of the guns to the mid-17th century also adds weight to this possibility. However, the potential also exists for the site being that of a previously unrecorded ship that was wrecked in the area.

The historical and archaeological value of this site cannot be overestimated. Little archaeological evidence has been obtained to date from 17th-century shipwreck remains in general and little is known of ship technology from the period, this being the first shipwreck from that time to be discovered and investigated in Irish waters. However, further investigation is obviously needed to determine the nature, extent and, if possible, the true identity of this wreck.