County: Dublin Site name: DUBLIN: 46–50, 52–57 Great George’s Street South/56–67 Stephen Street Lower

Sites and Monuments Record No.: DU018-132---- Licence number: 99E0414

Author: Linzi Simpson, Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd.

Site type: Burial ground

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 715514m, N 733760m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.341450, -6.265333

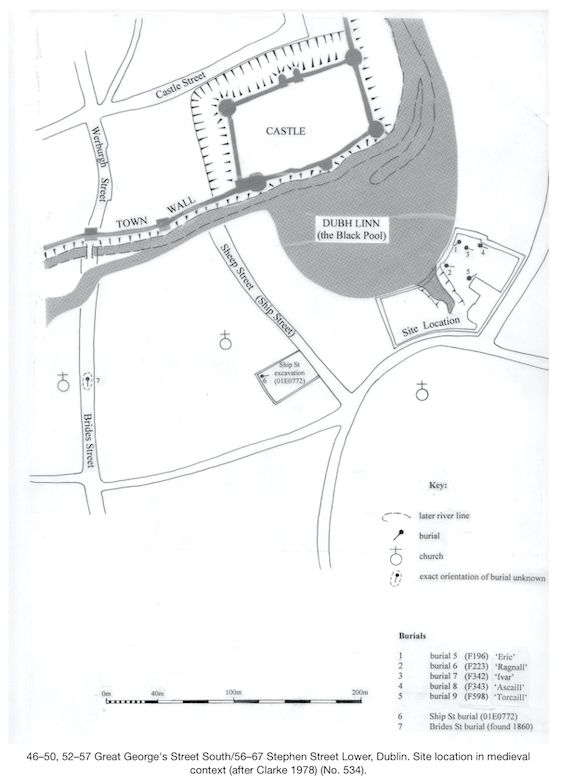

Excavations on a development site at South Great George’s Street/Stephen Street are now almost complete and the post-excavation analysis has begun. This large site, located to the south-east of Dublin Castle and the site of the ‘Black Pool’, has produced evidence of a Viking cemetery and associated settlement, along the southern flank of the pool, which can probably be dated to the 9th century. The post-medieval phases were also well represented by a series of laneways, cellars and latrines, as well as some sort of a metalworking industrial site.

The early levels revealed that the Black Pool originally extended into the site in the central area in the form of an inlet or river, which may have been in use as a landing point, as the coarse gravels produced a number of boat nails and an iron axehead, as well as various other pieces of metal. The eastern edge of the inlet was delineated by a series of gullies and what appears to represent a continuous slot-trench, which followed the line of the water. Evidence of settlement on the high ground to the east was also indicated by a series of large, distinctive post-holes (some with packing stones), metalled surfaces and the outlines of possible buildings, one of which may have been substantial in size. Several hearth sites were also identified, which produced evidence of foodstuffs, indicating that they were domestic in nature.

One of the hearths contained the remains of a human torso laid across it, although it was not burnt in any way. The burial was identified as a male who was under 25 years old (identification by Laureen Buckley), aligned with his head to the north-west. The skeleton had the remains of an iron object on his chest and, although this had corroded badly, it can probably be identified as a shield boss. A second burial lay approximately 15m to the east, but this was also badly damaged, lying in a shallow grave, cut into boulder clay. Preliminary inspection revealed that he was also a young, strong male, aligned with his head to the north-east. More importantly, he was buried with a relatively well-preserved iron shield boss on his chest and a tanged knife dagger beneath his left hip. A short distance away, two additional young male skeletons were located close to the north-eastern boundary of the site, establishing that the burials extended some distance across the site. One of the skeletons was very complete (head to the west), while the other only survived as a pair of legs (head to the west), but neither had any grave goods, although they were both disturbed in the post-medieval period, when any grave goods may have been taken. A fifth and final skeleton (head to the south-east) was found lying in a gully which contained a large amount of butchered animal bone. In keeping with the general pattern, this individual was tall and very strong and was estimated to be under 23 years of age. He was buried with his hands over his face and his legs had been disturbed shortly after he was buried. A very fine decorated bone comb was found positioned on the right side of his chest and this was probably originally within a cloak, as a zoomorphic pin (in the shape of a hare’s head) was found close to the right shoulder, and this was probably originally used to pin the cloak together. This skeleton also had a curious large metal object under his right shoulder, which is currently being investigated. It is possibly made of whalebone and copper alloy and is decorated with a herringbone design. It may form part of a purse, although this had not yet been established (Cathy Daly, pers. comm.).

These male warriors were presumably associated with the fortress, or Longphort, established by the Vikings in AD 841, which represented their first permanent encampment at Dublin. This Longphort was a slaving and trading base and is thought to have been located somewhere close to the Black Pool, accessible via the Poddle watercourse. The number and type of burials suggest that this area must represent some sort of cemetery or burial place, presumably in land under the control of the Dublin Vikings, the dead warriors being the result of the continual warfare that was well documented in the Irish annals. The burial ground may have been informal, as it appears to be very extensive, possibly extending as far west as Bride Street, where a furnished Viking burial was found in the 19th century. In 2002 a badly damaged single male burial was found by the writer at Ship Street Great, approximately 200m to the south-west of the site (Excavations 2002, No. 575, 01E0772). This skeleton had grave goods as well as part of a sword but has been dated by 14C to between AD 665 and AD 865 (two sigma 98%), fixing him firmly within the early phase of the Longphort. The South Great George’s Street burials can probably be dated similarly. The Viking activity on the site appears to have been limited in time span and by the late 12th century this area was under cultivation, demonstrated by the deposits of garden soil which extended across the site. Several hearths and post-holes indicate some settlement activity in this period, but this also appears to have been limited in time.

By the late 17th/early 18th century, the entire site was undergoing major redevelopment, as was the rest of Dublin. The Cromwellian and civil wars of the 1640–50s had wreaked havoc on the city and almost three-quarters of all buildings were destroyed in this period. This was followed, however, in the late 17th century, by a period of rapid expansion, the result of a flood of Dutch and Flemish refugees, followed by Huguenots, fleeing Catholic persecution. They settled extensively in Dublin, bringing with them the use of brick and a specific type of building, known as a ‘Dutch Billy’; these buildings were built in every available space. The site was ringed along the street frontage by a series of these early 18th-century buildings fronting onto Stephen Street and South Great George’s Street, several of which are be retained in the new development. The excavation also exposed the remains of several small Dutch Billies to the rear of the main houses, which were accessed by a series of laneways. Cobbled yards, cellars and latrines made up other features of the post-medieval phase and at least one metalworking industrial site was identified to the rear of the properties, suggested by the partial survival of several brick furnaces.

2 Killiney View, Albert Road Lower, Glenageary, Co. Dublin