County: Wicklow Site name: KINDLESTOWN CASTLE, Delgany

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR 8:17 Licence number: 0E00844

Author: Linzi Simpson, Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd.

Site type: House - fortified house

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 727551m, N 711841m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.141805, -6.093448

Introduction

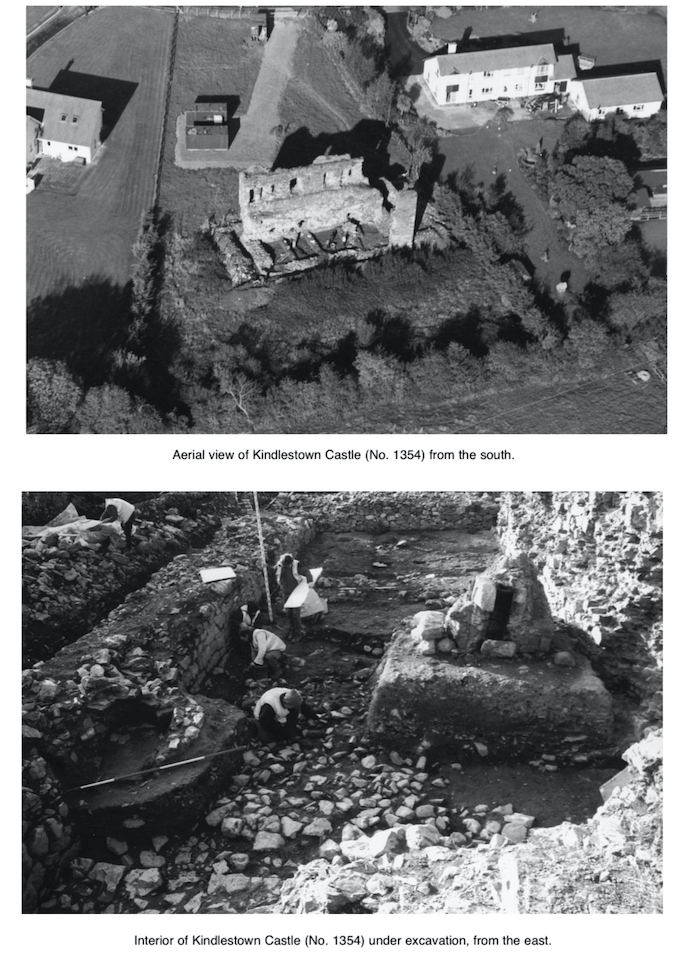

Excavations have now been completed in the interior of Kindlestown Castle, Delgany, on behalf of Dúchas The Heritage Service. The medieval castle consists of a rectangular hall-house-type structure, which measures externally 21m east–west by 9.8m by c. 8m in height (internally 18m east–west by 6.6m). Although the northern wall and part of the eastern wall survive generally intact to parapet level, the southern and western walls were comprehensively demolished in the post-medieval period. The surviving castle, two storeys high, is built of rough limestone, and the main features consist of a small projecting tower in the north-west corner, an original barrel vault at ground-floor level, and an entrance (at ground-floor level) and mural staircase in the eastern wall. The windows are small defensive loops in the exterior, widening into segmental-arched embrasures in the interior. Window-seats survive at first-floor level. The remains of a slated parapet and stone string-course are also visible in the front façade.

There are four antiquarian depictions by Du Noyer from the early 1840s (three pencil sketches and one water-colour) and these show the eastern side of the castle still intact. This appears to have been a narrow service tower, which extended well beyond the roof line. The flashing of the pitched roof was visible in the west face of the tower, which was still relatively intact in 1913 (when Canon Scott photographed it). The Du Noyer depictions also suggest that there was a watercourse on the northern side (possibly a moat, see below) and earthworks to the west.

In summary, the excavations revealed the remains of habitation in the medieval period in the form of metalled surfaces, post-holes and a hearth. Although no datable finds were made at the earliest level, the succeeding levels could be dated from the 14th century onwards. The castle appears to have been continually occupied and in use from this time into the 18th century, when at least two brick ovens were constructed. The excavation also established that the south and west walls, as revealed during excavation, represented a replacement wall rebuilt in the 19th century. These walls, while following faithfully the line of the original wall (and, in the case of the southern wall, built on top of the original medieval foundations), were drystone walls, incorporating fragments of the collapsed barrel vault, some with traces of wicker centring. The castle was probably repaired in response to the fact that it had been extensively plundered and large sections of the facing stones had been removed.

An enclosure

The castle may originally have stood in a large rectangular ditched enclosure, which measured 52m east–west by 18m and which was still visible in 1991. Only traces of the northern section of the moat are now visible, located 6.5m from the castle. This moat, marked by a shallow depression and nettles, measures 6m wide by at least 1m in depth. There was no excavation in this area.

The history of the castle

Historically, the castle was ascribed by Liam Price to Walter de Beneville but takes its name from the de Kenley family, prominent in the region in the 14th century: Albert de Kenley was sheriff of Kildare in the early 14th century and he probably received the castle after marrying into the Mac Giollamocholmog family, the dominant Irish dynasty in the region. The Meic Giollamocholmog controlled all the land in the area and their caput was at Rathdown, in Greystones, a short distance from Kindlestown.

The Wicklow area (then south county of Dublin) had been settled very peaceably after the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, for the most part because Domhnall Mac Giollamocholmog, the reigning Gaelic chief, sided with the new invaders and they became allies, safeguarding his land and tenants. Thus the first hundred years in Wicklow was very settled. By the late 13th century, however, the O’Byrnes and O’Tooles, forcibly moved to the Wicklow mountains, began to rebel, attacking and destroying the Anglo-Norman settlements. The construction of Kindlestown Castle, clearly a highly defensive building, was a direct response to the changing political climate.

By the mid-14th century, south County Dublin had been all but cleared of settlers, creating an opportunity for ‘frontier colonists’ to expand in the area. By the late 14th century the castle was in the hands of the Archbold family, one of the main staunch colonist families in the area, who gradually expanded their power base to include lands at Bray and Kilruddery. The castle remained in a frontier position throughout the medieval period, being taken by the rebel O’Byrnes in 1377, although retaken soon afterwards. The south and west wall was probably destroyed during the Cromwellian period, as were other castles in the area. Shortly after, the castle passed into the hands of the earl of Meath, who held lands at Kilruddery, Co. Wicklow.

Phase 1

Two phases can be identified in the construction, visible as a change in the type of stone used, a break in the render line in the front façade, and the use in the lower level of putlog holes, which are absent from the upper level. This combination probably suggests that the castle was constructed to first-floor level (including the barrel vault), after which construction was halted, although it is not known for how long. The Phase 1 castle was built of roughly cut/uncut grey limestone bonded with a distinctive crude mortar, which contained heavy grit and shell inclusions. The walls were over 2m wide and the quoins were of cut granite (local stone). The southern wall had a basal batter, while the foundations of the northern wall were composed of a series of projecting offsets. The barrel vault was clearly original to the Phase 1 building as the northern haunch forms part of the core of the standing northern wall. The excavation also revealed that the castle was originally roofed in purple slate, complete examples of which were found throughout the deposits. The remains of a deposit of small chips of slate at the south-east corner of the castle is probably related to the construction level of the roof.

Phase 2

The second phase followed the plan of the first and the north-west tower was completed, with garderobes feeding into the already existing chutes of Phase 1. A third garderobe was added at parapet level, but this was clearly not in the original plan as the chute only extends through the Phase 2 portion of the wall, screened by a squinch arch.

The entrance at ground-floor level in the east wall is difficult to date. The excavation revealed that the eastern wall continued across the line of the doorway, suggesting that it was originally a solid wall. However, this was only 0.25m in height, comprised of two courses, and there was no indication of the doorway in the west face. Two granite jambs, however, were located on the eastern side and were positioned 1.45m apart. These appear to have been inserted, disturbing the face of the wall, although this could not be firmly established. The level of the jambs, less than 0.2m from the boulder clay, is also relatively unusual as it suggests that the doorway entrance was very high. The doorway may have been inserted in Phase 2, replacing an original door at first-floor level, the remains of which may be shown as a broken ope on one of the 19th-century depictions.

The Phase 2 castle was constructed from a different type of stone, consisting of rough limestone with an orange/red hue, clearly from a different source. The walls were also thinner and possibly not as defensive (the thinness of the walls eventually led to the partial collapse of the eastern wall). What is of note, however, is the fact that the mortar used is very similar in type to that used in the lower course, suggesting that the same source of lime was used. The remains of an external render are clearly visible in the front façade of the Phase 2 section, indicating that the castle was completely rendered in Phase 2, the render probably adhering better to the upper levels because the mortar of this section of the wall was still fresh, unlike the lower portion (Ben Murtagh, pers. comm.). The use of regularly spaced putlog holes in the lower Phase 1 section was notable in view of their absence in the upper levels. Although putlogs may have been used and subsequently neatly infilled, the barrel vault was in position by this date, which would have facilitated the construction of the upper levels.

The deposits

The excavation revealed little stratigraphy that could be dated to the medieval period, although a large quantity of medieval pottery was recovered, along with two coins probably dating from the 14th century. It did establish, however, that the castle does not have deep foundations and sits directly on boulder clay. The western end of the castle had the remains of a metalled surface, presumably the original surface, and this was set on boulder clay. It was probably originally quite extensive but had been cut away by later 17th- and 18th-century activity in the central and eastern parts. This surface contained the remains of a large hearth, the burnt ash and charcoal of which extended throughout the western end of the castle. Numerous lumps of fire-reddened clay were also recovered from this deposit. The remains of some sort of stone drain, orientated north–south, were revealed in the central area, although badly truncated by later activity.

The boulder clay and redeposited boulder clay were also cut by numerous post-holes, some in linear arrangement, extending through the length of the castle (east–west). However, these could not be related to any known feature although several post-dated the castle walls. They may represent some sort of internal divisions within the barrel vault, which were replaced continually over time. Also of note were the remains of three massive post-holes, centrally placed in a linear arrangement, orientated east–west. These measured, on average, 0.3m in diameter by 0.35m in depth and were cut through the metalled surface. They appear to suggest the presence of some sort of internal support system, centrally placed at this end of the barrel vault.

A large channel was excavated through the western end of the castle in the late 17th century, orientated east–west, and this removed the medieval stratigraphy in this area. The cut may have acted as some sort of large soak-away as it was filled with loose boulders. The deposits over this feature, while post-medieval in date, also contained a large amount of medieval pottery, indicating that they represented disturbed medieval horizons.

Two ovens were located at the eastern end of the castle, both made of hand-made brick, which can probably be dated to the late 17th/early 18th century. One of the ovens was set within the window embrasure, removing the lower sill but obviously taking advantage of the position of the window to act as a flue. Only the lower three courses of the oven survived intact. The second oven was set into the southern wall at the eastern end and the facing was removed in this location. This oven (possibly part of a pair) survived relatively intact. It was suboval in shape with a flue on the western end and a stone slab floor. The interior was completely filled with layers of charcoal and ash and a large number of broken pantiles. A series of new clay floors were laid at the eastern end of the castle which could be associated with the ovens. A small rough stone wall was also constructed which separated the ovens from the remainder of the castle.

The upper deposits of clay, sealing the channel and extending throughout the castle, were substantial in depth and contained numerous lumps and mortared fragments of the collapsed barrel vault, including many with traces of wicker centring (the window embrasures show sections of well-preserved plank centring). The depth of the deposit may suggest that the area on either side of the roof of the barrel vault was infilled with clay to create a level floor (Ben Murtagh, pers. comm.).

2 Killiney View, Albert Road Lower, Glenageary, Co. Dublin