County: Kerry Site name: GORTATLEA

Sites and Monuments Record No.: N/A Licence number: 01E1101

Author: Margaret McCarthy, Archaeological Services Unit, University College Cork

Site type: Souterrain

Period/Dating: Early Medieval (AD 400-AD 1099)

ITM: E 491396m, N 609454m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.226119, -9.589698

A previously unrecorded souterrain was uncovered by a mechanical excavator on 13 March 2001 during road improvement works on the N22 route between Tralee and Killarney. The site is in Gortatlea townland in a landscape dominated by prehistoric and early medieval monuments. The souterrain was located between two curvilinear ditches that were excavated by Aegis Archaeology Ltd as part of previous road improvement works in the area (see Excavations 2001, No. 569).

A cavity in the north wall of the chamber became apparent during the removal of the hedgerow forming the boundary of the old road. The opening was sealed with plywood but the location of the souterrain was accidentally reburied during subsequent road works in the area. The site was tested on 20 September 2001 by Michael Connolly (see Excavations 2001, No. 571) to relocate the souterrain. This work established the exact position and extent of the monument and it was recommended that full excavation be undertaken prior to any further road works in the immediate vicinity of the site as the location of the site was scheduled for incorporation into the new road.

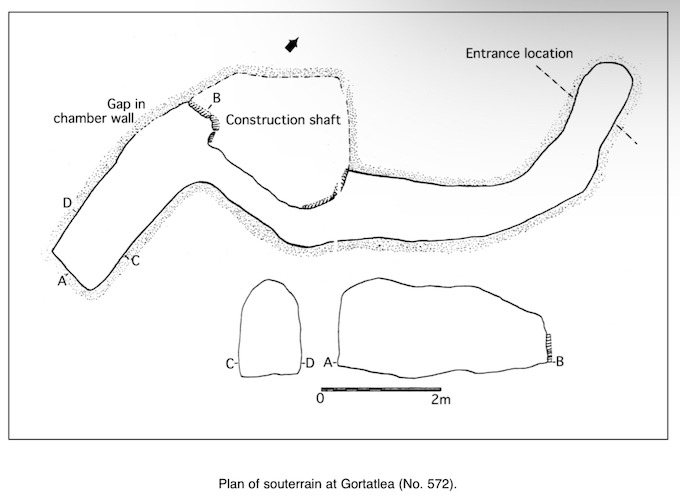

The site was inspected by the writer on 21 October 2001. The trench already excavated was visible, with two blocked-up openings to the souterrain at either end. Access to the chamber was gained through the western opening. A passage exited the chamber to the east and a blocked-up construction shaft was apparent to the north-east. A deposit of burnt soil and charcoal noted on the surface outside the termination of the passage appeared to mark the original entrance into the souterrain.

The earth-cut souterrain is located between two concentric ditches, which were excavated under separate licences by Michael Connolly. The inner enclosure was excavated in May 2000 (Excavations 2000, No. 434, 00E0779) and charcoal from the fills of the ditch indicated that it was early medieval in date. The excavation also revealed earlier features and structures which ranged in date from the Mesolithic/Neolithic transition period to the Middle Bronze Age and the Iron Age. The western and eastern circuits of the outer concentric ditch (see Excavations 2001, No. 569) were exposed on the limits of the road-take and these respected the curvature of the inner enclosure. The northern and southern circuits of the outer ditch lay beyond the limit of the acquired property for the road. The earth-cut souterrain appeared to be located inside the southern extent of the outer ditch but its exact position in relation to the overall monument could not be established until its excavation was complete.

The excavation commenced on 12 November 2001 with the exposure of the two openings in the souterrain which had been sealed with plywood. Entrance was then gained through the cavity in the north wall of the chamber, and a ground-plan and cross-sectional profiles of the chamber with intact roof were drawn. Much of the roof of the passage had collapsed during previous machine-trenching and it was deemed unsafe to spend any more time here than was absolutely necessary. In the interest of site safety, it was agreed, in consultation with Dúchas, that the roof of the chamber and what remained of the passage roof be deliberately collapsed to allow for excavation of the floors. This approach also allowed for sufficient light and room to carry out the excavation.

The souterrain was a simple earth-cut monument with a single chamber and passage. It was oriented east–west with the entrance on the eastern side. The floors of the passage and the chamber were cut into natural shale, but a thin layer (0.15m) of compact redeposited subsoil formed a smooth floor surface in both areas. The layer consisted of a sticky yellow clay with moderate inclusions of charcoal and appeared to have been deliberately introduced into the souterrain to create a level floor surface.

No clearly visible entrance to the souterrain could be defined during the excavation. It would seem that the original construction of the N22 and the recent removal of the road boundary caused its destruction. The entranceway may have been through a vertical shaft, and the burnt spread noted outside the opening to the passage on the east appeared to denote the entrance location. Excavation of this feature revealed an extensive spread of dark charcoal-enriched sandy silt with large quantities of heat-fractured medium-sized stones. It varied in depth from 0.11m at the north-eastern edge to 54mm as it approached the opening to the passage. A small amount of fragmented burnt bone was recovered from the fill, all animal in origin. The charcoal layer was removed to reveal a shallow cut feature of almost pit-like proportions, but it became apparent that this feature represented the base of the entrance shaft into the souterrain. The cut sloped gently towards the opening to the passage which was exposed during test excavations on 20 September 2000. There were just three sides to the cut and these corresponded to the dimensions of the passage. A layer of yellow boulder clay overlay the charcoal layer as it approached the passageway and this represented recent roof collapse. Removal of the redeposited clay indicated that the charcoal deposit extended into the passage for a distance of 0.67m, where it thinned to a depth of just 0.02m. The original floor surface of the souterrain was exposed after removal of the charcoal. It was extremely reddened in places as if burning hearth debris had been dumped into the entrance shaft.

Much of the roof of the passage had collapsed during grading of subsoil before archaeological work began on the site. From the presumed entrance at the east the floor of the passage sloped gradually downwards towards the chamber at the west. It measured 6.8m in length and averaged 0.9m in width. In cross-section it was steeply U-shaped with a relatively flat base. Various height measurements were taken before the remainder of the roof was collapsed, and these averaged 0.95m.

The floor surface along the length of the passage consisted of a heavily trodden yellow clay. This appeared to be natural in origin but it was removed in order to be certain that there were no other deposits on the base. In places there were uneven mounds of boulder clay which appeared to represent episodes of minor roof collapse. A large chunk of charcoal was found embedded into the clay in the central area of the passage against the northern side wall. Other finds from the passage included a cow pelvis and a pig radius which were resting on the surface near the entry to the chamber.

The passage led into a single rectangular chamber with vertical side walls and a slightly vaulted roof. The chamber survived in good condition except for the northern end wall, which was partially destroyed during the removal of the road boundary. The ceiling sloped upwards towards the south, so that the chamber was 0.86m high at its northern end, increasing to 1.52m at the southern end. The width of the chamber at floor level was 1.02m and this narrowed to 0.59m at roof level. It measured 3.5m in length and averaged 0.99mm in width. The roof, side walls and floor of the chamber were all cut into boulder clay and natural shale. A layer of redeposited boulder clay covered the floor of the chamber and this varied in depth from 53mm to 72mm. Four adult cattle teeth were found embedded in this layer. A primary localised deposit of loosely compacted stony silt with a thin lens of charcoal at the base was noted underlying the boulder clay at the east side wall adjacent to the passage exit. Charcoal flecking and staining were noted across the entire surface of the chamber floor but there were notable concentrations at the northern end. The removal of the boulder clay and the localised deposit revealed a loose natural shale surface throughout.

The base of a backfilled construction shaft was noted at the junction of the passageway and the chamber during the original site survey. The clay-cut shaft led to the surface and the base was blocked by drystone walling. The excavation failed to define the full dimensions of the shaft as the northern side was destroyed by machine activity during the removal of the road boundary. The surviving portion measured 0.66m in width and 1.95m in depth. The construction shaft was clearly visible in the section face when the roof of the chamber was deliberately collapsed. Upon completion of the tunnelling work for the chamber and passage, the construction shaft was backfilled with sterile, stony redeposited subsoils. A number of large flat stones were set vertically into the ground at the base to prevent the spoil from working its way into the chamber or passageway.

The souterrain at Gortatlea is of an earth-cut type commonly found in south-west Ireland. Entrance may have been by means of a vertical shaft or pit which was destroyed during the course of the roadworks. A single passage then led into a large rectangular chamber. The primary motive for the construction of this souterrain would seem to have been for storage as access to the chamber was relatively easy and the extremely compact nature of the floor surface suggested that the chamber was regularly used. While there was no complex network of creepways and chambers to indicate that it was originally constructed as a place of refuge, it would have been an obvious place to store valuables or to retreat to during attack.

The excavation indicated that the souterrain was located well within the confines of the outer ditch excavated in 2000. This concentric ditch would appear to be contemporary with the inner enclosure but radiocarbon dates for the outer line of defence were not available at the time of writing. The excavation of the souterrain established that there is no stratigraphic link between it and the projected southern circuit of the outer ditch. The only relationship that can be established at the moment is that the souterrain is located between the inner and outer enclosures. The former existence of a bank between the two ditches is considered by Connolly (2001) but there was no clear evidence for bank material during the excavation. If such a bank ever existed, the souterrain was either sealed by bank material or was incorporated into the defences.

There is, as yet, no definitive evidence that the souterrain is associated with either of the two excavated ditches at Gortatlea, although it probably relates to the final phase of early medieval activity represented by the inner enclosure. The association of ringforts with souterrains is well documented (Warner 1979; Clinton 2001), and of the 450 sites that are known to exist in the Iveragh and Dingle peninsulas alone the majority are associated with ringforts or with unenclosed hut sites of early medieval date (Hayes 1999). The excavators of the inner enclosure at Gortatlea are not entirely convinced that the site represents a ringfort as there is no evidence for an associated bank. The outer ditch is concentric to the inner enclosure, but until the radiocarbon dates are obtained for this feature it has to be considered that the outer enclosure is not contemporary with the inner one. Charcoal from the souterrain has been submitted for radiocarbon dating and the results will be crucial in establishing the relationship of the souterrain to the overall monument at Gortatlea.

References

Clinton, M. 2001 The souterrains of Ireland. Bray.

Connolly, M. 2001 Archaeological test excavations on an earth-cut souterrain at Gortatlea, Co. Kerry. Kerry County Council Archaeological Reports.

Hayes, A. 1999 A study of souterrains and unenclosed settlement on the Iveragh Peninsula, Co. Kerry. Unpublished MA thesis, University College Cork.

Warner, R.B. 1979 The Irish souterrains and their background. In H. Crawford (ed.), Subterranean Britain, 100–44. London.