County: Dublin Site name: DUBLIN: Tram Street/Phoenix Street

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR 6:20 Licence number: 01E0229

Author: Franc Myles, Margaret Gowen & Co. Ltd.

Site type: Historic town

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 714674m, N 734372m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.347129, -6.277717

This summary describes the results of two adjacent excavations undertaken along Line A of the proposed LUAS, the light rail transport system for Dublin. The brief in both areas involved ground reduction to a level where there would be no disturbance of archaeological deposits during the construction phase. This necessitated an average reduction of 1m, with 0.6m for the track formation and a buffer zone of 0.4m between the concrete foundation and the underlying deposits. It was found necessary on the Phoenix Street site to excavate to a lower level owing to a rise in the surface caused by 18th-century dumping.

The excavated areas were located along two strips of ground on either side of Bow Lane. The area to the east, between Bow Lane and Church Street (Tram Street), was excavated to the required level over a period of six weeks. The area to the west of Bow Lane ran parallel to Phoenix Street North and was separated from it by a late 19th-century concrete wall. This smaller area was excavated to the required level over a period of four weeks. The work was undertaken between 2 April and 15 June 2001.

The cartographic evidence suggested that the area had been heavily industrialised in the 19th century. Two iron foundries occupied the area of the Tram Street site, the Eagle Foundry fronting onto Church Street and the Hammond Lane Foundry, which had encroached over the whole site by the turn of the 20th century. Earlier maps indicated the presence of a laneway across the site, linking Bow Lane and Church Street. This may have developed over the late 17th century to provide access to industrial spaces to the rear of Hammond Lane as depicted by John Rocque (1756).

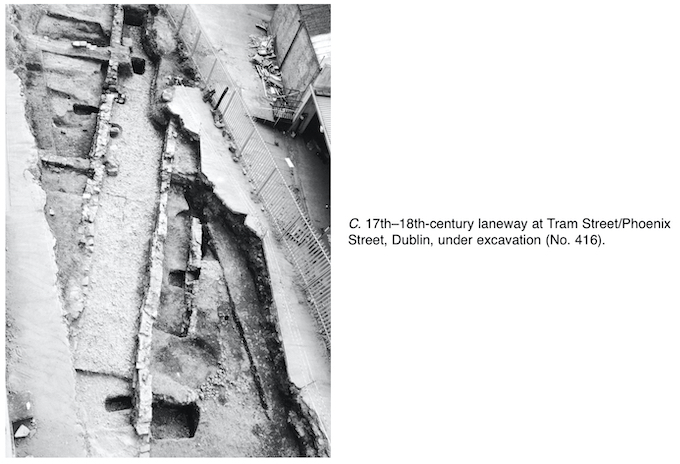

The excavation identified five phases of activity over the Tram Street site. Phase I related to post-medieval reclamation work and was characterised by the presence of large dumps of river gravels and garden soils. Phase II related to the late 17th- and early 18th-century domestic occupation of the site, with walled gardens backing on to the metalled laneway transecting the site. It was under one of these gardens on the north side of the lane that a skeleton was recovered. Phase III included the further consolidation of the laneway and the early industrialisation of the area. Phase IV was characterised by the upper levels of solidified foundry waste, which covered most of the site. Phase V was mostly associated with 20th-century disturbance, which took the form of massive concrete foundations. Natural subsoil was not located on the site, although John Ó Néill’s initial assessment located compact clays and river gravels at depths below the limits of the excavation.

Successive layers of post-medieval dumping were recorded on the Phoenix Street site, with a considerable area of the site still open on the 1756 depiction of the area. The whole area had been built upon by the 1840s and the foundations of these and earlier buildings were recorded. Two stone-lined well shafts were recorded, one with its capillary pump surviving.

The Phase I levels on Tram Street would appear, on the basis of the finds recovered, to date from the period after the construction of Arran Quay. While there was undoubtedly medieval occupation in the area, as evidenced in Alan Hayden’s 1990 excavation (Excavations 1990, No. 40) and the various references to Hangman’s Lane (Hammond Lane), the gravels recorded in section and the garden soils sealing them were introduced in quick succession, probably to create gardens for the new plots. While there has been no evidence recovered for a medieval building line along the northern side of Hammond Lane, it is likely that it was formally built upon during this period, with associated garden plots extending northwards to the rear. Speed’s map of c. 1610 depicts several houses here extending as far west as the corner of Bow Lane.

It is unlikely that the deposits of garden soils recorded in Phase I date from the 16th-century occupation of the site; the lower of the two deposits, F70, seals the deposit of river gravels, which is too substantial to have been deposited naturally. An accumulation of garden soil over natural gravel would also be unlikely without the formation of a clay sealant over the gravel. Although Ó Néill recorded the presence of medieval pottery within F70, this material is presumably intrusive to the context, which itself was brought onto the site after the ground was consolidated.

In any case, the earliest documentary evidence for building here pre-dates the reclamation work, when in 1637 the lord chief justice, Gerard Lowther, was granted a plot of ground beside a stable which was already in his possession (Gilbert 1889–1944, III, 331). The same year, Charles I was granted a large plot beside Lowther’s holding to build a mint house. By 1674 the royal site had not been developed and the plot was granted to a John Greene, who had not developed it by 1682. In that year a William Ellis was granted the whole shoreline from the old bridge westwards to the gates of the Phoenix Park. He was to construct a quay 11m wide, leaving in position ‘the present highway where coaches and carriages now pass fourty feet wide’ (ibid., V, 237). This is a reference to the Hammond Lane–Benburb Street thoroughfare.

By the time of the publication of Brooking’s map of 1728, the whole area had been built up to the quays and the laneway had developed to service the rear of the Hammond Lane plots, though it did not extend as far as Church Street. While it is likely that the buildings and gardens of the 1680s development took the form of those illustrated by Rocque thirty years later, the area as a whole had taken on a different social complexion, becoming more industrial.

The evidence for the laneway at this early level is strong. It is likely to have developed immediately after the plots were established to provide access to the back gardens and would appear to have been delineated from the gardens by timber divisions. The masonry walls were constructed later as the gardens were converted to the warehouses or stables depicted by Rocque.

The limited area excavated north of the laneway produced a sequence of garden deposits, which were later cut into by pits filled with evidence of demolition debris. This activity pre-dates the warehouse/stable structure depicted by Rocque.

A cellar return excavated in Phase II is undoubtedly part of the large building depicted by Rocque on the southern corner of Bow Lane and the unnamed laneway running across the site. No. 3 Bow Lane and its neighbour, No. 2, appear to have been rebuilt at some stage before the first edition of the Ordnance Survey map and the demolition material recorded in the laneway and within the space itself may derive from this. The cellar space was in the very south-western corner of the excavated area and it was not possible to establish its relationship to structures to the south and west. There was, however, no evidence of access at the excavated level, suggesting that a ladder originally accessed the space or that it was under a now-truncated floor level.

A decorated plate recovered from the cellar fill, dating from 1748, may commemorate a turbulent year in Dublin, when political tensions were exacerbated by a dispute within the city assembly concerning the aldermen’s almost exclusive control over office-holding and patronage. Charles Lucas, an apothecary and controversialist of some ability, highlighted the cause of the freemen and city guilds with a series of pamphlets, the contents of which were eventually to open him to charges of sedition. The political vacuum caused by the deaths of the two sitting MPs in 1748 led to renewed agitation in the city and saw Lucas begin to attack the government itself. The resulting election campaign was the first in the country to politicise the local press (Lucas himself was later to help found the Freeman’s Journal) and to give the city’s 4000-odd electorate an idea of the power that they could wield under the right circumstances. Lucas himself was charged with sedition and forced into exile, where he remained until his election to parliament in 1761.

The well in the yard to the rear is typical of similar structures recorded elsewhere in the city. Two similar examples were recorded in Phoenix Street to the west. It is likely that the well went out of use as piped water was introduced to the area towards the middle of the 18th century. In 1741 the Piped Water Committee of the City Assembly (later to be known as the Committee for Better Supplying the City of Dublin with Piped Water) recommended that the Liffey be tapped at Islandbridge, to relieve pressure from the city basin at James Street (Gilbert 1889–1944, IX, 32–3). In 1746 a consignment of timber consisting of 800 to 900 yards of ‘good round fir … 10 feet to 14 feet long, 15" to 18" diameter exclusive at the butt end’ was awaited from Norway (ibid., IX, 198). The main ran along the north quays into the city, and the Smithfield area would have been one of the first beneficiaries of the new water supply.

The close corroboration between the dating of the material recovered from the backfill of the cellar and the introduction of piped water to the area, as evidenced by the well’s going out of use, would indicate that the building occupying the Bow Lane plot may have been demolished as early as the 1750s or 1760s.

An adolescent male skeleton was recovered from an area depicted by Rocque as a garden (or yard) between two warehouses or stables just to the north of the laneway. The location of the burial is approximately 22m south of the present precinct wall of St Michan’s Church and graveyard, which has remained stable since at least 1756, and possibly since Bernard de Gomme’s depiction of 1673. The earliest representation of the church precinct is on John Speed’s map of c. 1610, which appears to depict the southern extent of the church precinct extending further to the south. Beth Cassidy’s 1993 excavation in this area (Excavations 1993, No. 61, 93E0026) did not record the presence of human skeletal material, which would suggest that the southern precinct boundary has remained stable since the 14th century. All the evidence therefore suggests that the Tram Street burial is an isolated one, dating from the middle of the 18th century.

The structures and deposits associated with the Phase III occupation of the site date from the period just before the area became industrialised. The activity recorded to the rear of the Bow Lane property, the backfilling of the well and the demolition of the early 18th-century building point to the future shape of the area, which was to become increasingly less residential and more industrial.

There was little evidence to suggest that the walls defining the laneway were rebuilt along the lines of earlier masonry walls. Their relatively late construction may have been a function of the necessity to have load-bearing walls at least on the southern side of the laneway. In this area Rocque has depicted stabling or warehouse activity running off from the F3 wall, which presumably covered the gardens that must have existed to the rear of the Hammond Lane plots (the evidence for which has been outlined in Phases I and II above). While the laneway may have evolved to service these plots, there was no evidence within the trench that the 1756 structures were accessed from the laneway. Nor was any evidence found for internal divisions or occupation surfaces in this area.

On the whole it is likely that the process that reduced the walls adjoining the laneway to their excavated heights also removed the occupation evidence for this period south of the laneway.

One of the walls recorded north of the laneway can be located on Rocque’s map and would appear to be part of one of the structures referred to above. The wall, F9, was relatively narrow and did not appear to be of sufficient structural quality to be any more than a garden wall.

The rebuilding activity suggested by the construction of the F19 brick wall along the southern side of the laneway may have been necessitated by the failure of an earlier stretch of the wall. The disturbance, additionally indicated by the slumping of the F10 cobbled surface, may be due to the presence of a large linear medieval trench recorded by Alan Hayden in 2000 (Excavations 2000, No. 250), which extends in this direction from the south-east.

Phase IV activity related to a general level of solidified foundry waste, which extended over much of the centre of the site. This material was up to 0.4m thick in places and consisted of a heavy iron deposit which had percolated through the cobbled surfaces in the laneway to the levels below. Phase V consisted of disturbance caused by the insertion of massive concrete foundations for foundry equipment. This had truncated much of the archaeological evidence in the eastern end of the site and was in places up to 0.8m thick.

The deposits recorded on Phoenix Street suggested that the area had been an open dumping ground until the mid-18th century. Up to 1.5m of dumped material was recorded underneath the foundations of the 18th-century houses depicted by Rocque. The finds recorded from the earliest levels excavated suggest a mid-17th-century date and include imported pottery and fragments of clay pipe and fine glassware. As has been indicated elsewhere in this volume, in the excavation summary for the monitoring associated with the LUAS project (No. 359, Excavations 2001), this particular location has been used for dumping since at least 1468, when this end of Hammond Lane was officially designated for this purpose by the city assembly (Gilbert 1889–1944, I, 329).

Reference

Gilbert, J.T. 1889–1944 Calendar of ancient records of Dublin, in the possession of the municipal corporation of that city. Dublin.

2 Killiney View, Albert Road Lower, Glenageary, Co. Dublin