2000:0055 - CARRIGORAN (Area EX1), Clare

County: Clare

Site name: CARRIGORAN (Area EX1)

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR 51:171

Licence number: 98E0338

Author: Fiona Reilly, for Valerie J. Keeley Ltd.

Author/Organisation Address: Wood Road, Cratloekeel, Co. Clare

Site type: Excavation - miscellaneous

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 538907m, N 667233m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.752708, -8.904971

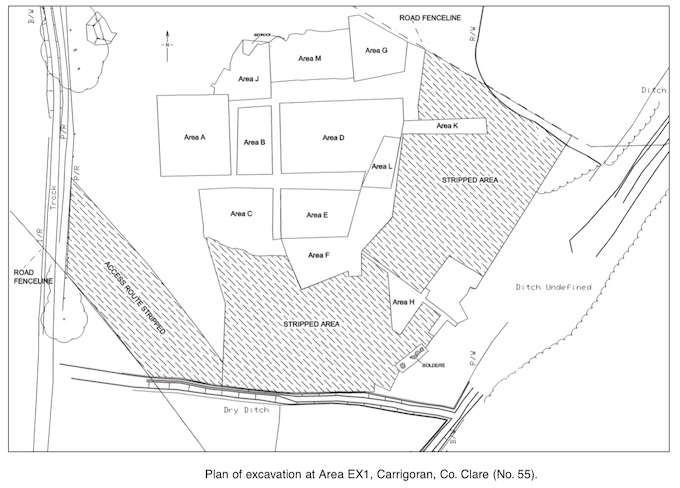

The site at Carrigoran was excavated because it was on the route of part of the N18/19 Ballycasey to Dromoland Road Improvement Scheme. The preliminary report can be found in Excavations 1998, 14–15. It was a large site (110m x 100m) on rough grazing land, on a gentle south-easterly slope, to the west of Newmarket-on-Fergus and north-east of Carrigoran House. A stream flowed through a marshy area to the south and east of the site into Lough Gash to the north-east. There were ten main areas of investigation. Disturbance from agricultural activity had resulted in the truncation of several features and the discovery of finds of varying type and period immediately below the sod. Excavation of the site produced evidence for prehistoric, medieval, post-medieval and modern activity. Artefacts such as polished stone axeheads, flint and chert artefacts, prehistoric pottery, quernstones, copper-alloy stick-pins, blue glass beads, post-medieval pottery sherds and late glass and pottery sherds were found.

Six main phases were identified throughout the majority of the site, as well as a fulacht fiadh (Area H) that was not stratigraphically related to the rest of the site. Phase 1: the earliest phase of post- and stake-holes cut into the mid-orange subsoil; Phase 2: post-Phase 1 build-up of material; Phase 3: field wall and trench activity; Phase 4: post-field system construction; Phase 5: field system destruction; Phase 6: 19th-century ceramic dumps and ditch excavation.

Phase 1

This phase produced evidence of possibly three structures partially enclosed by a post-fence (Area A), a series of pits containing charred remains (Area C) and linear post-hole features (Areas D and G). It was difficult to date because only one artefact was found directly associated with it (a chert end scraper (Brady 2001) was found in the fill of one of the pits containing charred remains in Area C). It could be assumed that the earliest stratigraphic phase dates to the period of the earliest artefacts found on site. This may not be the case, however, as charred oat remains were found in the pit fills in Area C. Oats usually indicate an early medieval or later date.

Three possible structures (A, B and C) were identified in the north-western area of the site. They were aligned roughly north–south and seem to have been at least partly enclosed on the western side by a post-fence, possibly double. The most northern structure (Structure A) was constructed of posts, with a central line of double stakes possibly representing an internal divide. Its internal width was c. 4.2m (roughly north–south). Owing to the absence of C451 (the subsoil through which the posts were inserted) it is not possible to determine the length of the structure. If the double row of central stake-holes is taken as a rough indication of length, it can be suggested that it was at least 5.2m long. The double row of stake-holes may have formed an internal division. The position of three post-holes at the south-western external corner and the two other stake-holes, one (C331) to the north of the group of three and one (C357) to the south of the southern wall, suggest that the roof of the structure was supported externally, perhaps as a hipped roof.

It is possible, however, that the structure was square or sub-square with an entrance at the north-western corner. In that case the pit C371 would have had a central location, and the double row of stake-holes would have formed a screen to the left of the door and partly divided the interior.

The pit (C371), c. 0.7m in diameter and 0.3m deep, was located 1.2m from the centre post-hole (C370) in the southern wall. Burnt soil, stone, bone, charcoal and charred seed remains were found in the pit, but there was no evidence for intensive burning at its base. This implies that it is a waste or storage pit and not a fire-pit. There is therefore no indication of a hearth within the surviving structure. The secondary pit fill (C393) contained the charred seed remains of hulled barley, possible barley, indeterminate cereal and grass seeds, and weeds such as dock, cleaver and plantain. The seeds of dock and cleaver are associated with waste ground or could also be crop weeds (Johnston 2001). It is possible that this pit contains the waste products from crop processing. If this is an internal pit, however, it seems more likely that it was used for storage. The absence of oats in the pit fill may indicate a prehistoric date, unlike some of the pits in Area C, which contained charred oat grains indicative of the early medieval period.

Structure B, also constructed of posts, was located 12m to the south of Structure A. This possible structure was oval with internal dimensions of 4.8m (east–west) by 2.9m. A stake-hole (C300) in the centre suggests that the roof was centrally supported. The diameter of the post-holes and especially that of the central stake-hole suggest that the construction was quite light. No hearth or associated features were found in the structure. Stake-holes to the south of this structure may form settings for features constructed above ground that therefore left no further evidence in the archaeological record.

Tenuous evidence for another structure was found between Structures A and B. Sometimes the only hint to the ground-plan of medieval houses is the survival of curvilinear drainage gullies that would have collected water dripping from the eaves (Edwards 1990, 22). It can be presumed that builders of earlier houses may also have drained roof water in this way; therefore it does not necessarily date Structure C to the medieval period. There was no evidence of an internal hearth found. The three internal stake-holes may have had a structural function.

The lack of associated artefacts and stylistic characteristics means that the dating of these structures cannot be definitely determined.

Eight pits, which did not form any obvious pattern or have a set form, were located in Area C to the south of Area A. They were all dug into C451, the natural subsoil, and ranged in size from 1.47m x 1.33m (C422) to 0.5m x 0.29m (C464). They varied in form from deep bowl-shaped examples like C462 to shallow depressions like C468. Several contained the remains of charred seeds: C455, C457, C462 and C468. Many contained charcoal, and at least two had evidence of scorching (C457 and C462). Analysis of the charred seed remains of four fills was carried out. It was found that hulled barley, indeterminate cereals, oats and hazelnut shells predominated. The high level of abrasion and encrustation on the seeds suggests that they had been disturbed and possibly redeposited (Johnston 2001). It can therefore be suggested that the final function of the pits was as waste pits and not to store cereal grains. An exception to this is the pit C457. The evidence for disturbance on the seeds in one of its fills was less than on grains in the other pits. There was also evidence of in situ burning on the sides of the pit, suggesting that it may have been a storage pit. Evidence of scorching was also found in the large, well-defined pit C462. This suggests that this pit was also once a storage pit that had been sterilised by fire. It therefore seems likely that the pits in this area were once used for grain storage, but their final function was of waste disposal.

The occurrence of oats in the cereal remains indicates that the final use of these pits was probably in the medieval period. The complete chert end scraper found in one of the pits may have been an intrusive find. If these pits are contemporary with the structures in Area A to the north, it implies an early medieval date for them also. The discovery of a fragment of the rim of a rotary quern in a pit (C883) indicates that cereals were processed on site. The other rotary quern fragments found in disturbed contexts may therefore relate to this phase of activity. Rotary quernstones were introduced to Ireland in the 1st or 2nd century AD and are found on many early medieval and medieval sites (Carey 2001). The occurrence of the rotary quern fragment at this level and the possibility of the Class B comb fragment also belonging to this phase reinforce the theory that the pits containing cereal belong to the early medieval period.

This phase in Areas D and G is also represented by pits and post-holes cut into the natural subsoil. The post-holes in Area G do not form any discernible pattern, so they cannot be interpreted as a structure. They are probably related to the post-holes in Area D to the south. Three associated pits, C797, C795 and C794, were interpreted as a hearth feature because there was evidence of intense burning, though there was not a high proportion of charcoal found.

Two extended inhumations, one of a female and one of a male, were found. No evidence for coffins was found, so the bodies may have been shrouded. They were orientated roughly east–west.

Phase 2

In some areas a natural build-up of material occurred over Phase 1 and was preserved under the field walls of Phase 3.

Phase 3

In the early medieval period several small, stone-walled and ditched fields were located on the site. The curvilinear limestone walls were mostly well constructed. The ditches also curved. Evidence for iron-smelting or smithing was found in two areas of the site in the form of furnace pits and much slag. A large pit contained the remains of crop-processing in the form of charred, hulled barley and indeterminate cereal grains.

Only one artefact was found in the fill of one of the field ditches—a well-preserved end-plate of a Class E bone comb. This plate had no staining from iron rivets on its rivet-holes, suggesting that bone pegs were used. Nor was there any sign of polishing or wear from use. These both suggest that the comb was lost during manufacture and, since the end-plate is in good condition, may have been discarded or lost in the ditch soon after. Combs of this type have a pre-9th- to 10th-century date. They had four narrow side plates and were normally decorated with perforated holes down the centre. No complete example survives, but they were longer than 79mm (Dunlevy 1988, 362). It can therefore be suggested that the ditch silted up in the early medieval period.

Phase 4

This consisted of material that built up after the construction of the field system but before the destruction of the field walls.

Phase 5

The field system was destroyed and left as a rubble deposit. The rubble was generally of regular width (3–4m), giving the impression that it once formed a low bank, perhaps acting as a boundary in itself. It may also have acted as a focus for stones during field-clearing. The rubble itself was made up of small to medium stones. It is possible that the larger facing-stones were robbed to build other structures in the area, perhaps the extant 17th-century fortified house to the east (SMR 51:23). Possible evidence for a robber trench (C243) was found to the south of the remains of C8 in Area A. Some of the rubble, especially in Area D, was disturbed and crushed, probably by extensive ploughing.

Phase 6

This phase is represented by deposits that contained 19th-century ceramic sherds and glass sherds, as well as blue glass beads and other artefacts. These deposits were found immediately below the sod. A large ditch was also found at this level. It ran through the eastern part of the site in a northerly direction and may be related to ditches marked on the first edition OS map for the area.

Area H

This fulacht fiadh was found 30m to the south-east of the main area of activity. It consisted of a low oval mound of burnt sandstone and limestone, 16.5m (north–south) by 7m with a maximum height of 0.4m. Three pits were found under the burnt mound and cut into the underlying marl. One has been identified as a possible trough. It was unlined (1.6m x 1m). The mound was later covered by silty flood material probably from the stream to the east.

References

Brady, C. 2001 Appendix 12, Lithic analysis. In ‘Final excavation report for 98E338’. Unpublished, Dúchas.

Carey, A. 2001 Appendix 6, Report on the stone tools from Area 20, Carrigoran, Co. Clare. In ‘Final excavation report for 98E338’. Unpublished, Dúchas.

Dunlevy, M. 1988 A classification of early Irish combs. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 88C (11), 341–422.

Edwards, N 1990 The archaeology of early medieval Ireland. London.

Johnston, P. 2001 Appendix 11, Analysis of charred seed remains. In ‘Final excavation report for 98E338’. Unpublished, Dúchas.