County: Limerick Site name: ANNAGH, CO. LIMERICK

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR LI006-079 Licence number: 92E047

Author: RAGHNALL Ó FLOINN

Site type: Neolithic graves

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 569126m, N 658237m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.674421, -8.456519

Introduction

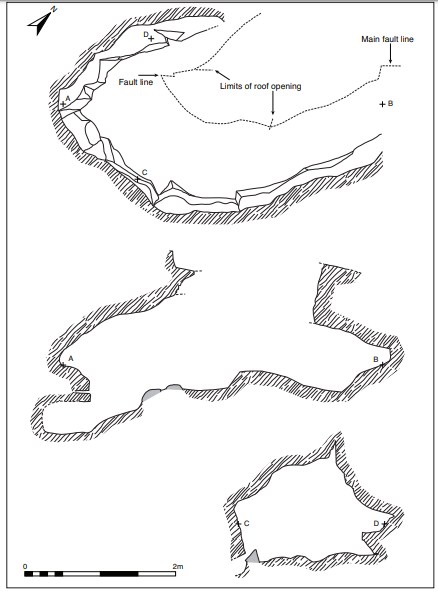

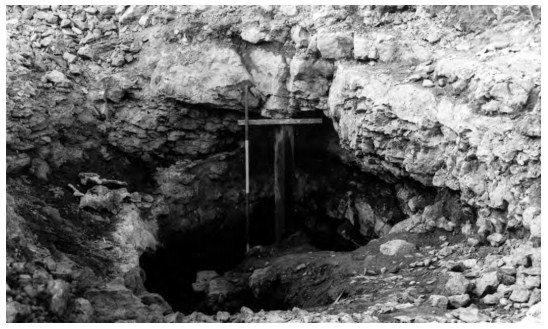

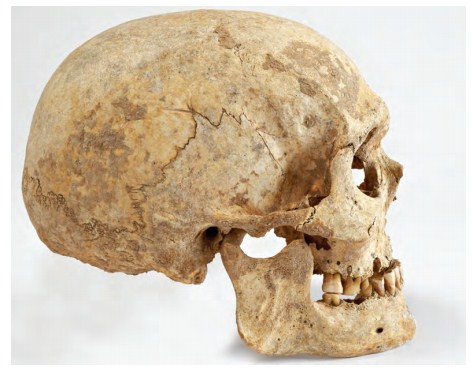

During quarrying operations on 27 February 1992, human remains were discovered in a cave near Limerick City when a digger was stripping topsoil from the limestone quarry in advance of blasting. The digger dislodged a large, pillar-like slab, revealing an opening 0.9m by 0.9m and exposing a cavern in which two skulls were visible. The site was reported to the Museum by the Garda Síochána at Killaloe. An initial inspection of the site was carried out by Ms Celie O’Rahilly, archaeologist with Limerick City Corporation. This revealed that the site consisted of a natural cavern 3–4m long and 2.5m wide containing two human burials, one crouched and one apparently extended. Two pottery vessels of Linkardstown/Drimnagh type were also noticed, fixed firmly to a ledge in the south-western end of the cavern. Excavations were carried out in March and May of 1992 by Raghnall Ó Floinn assisted by Stella Cherry, Siobhán Geraghty and Celie O’Rahilly. The human remains were examined by Barra Ó Donnabháin.

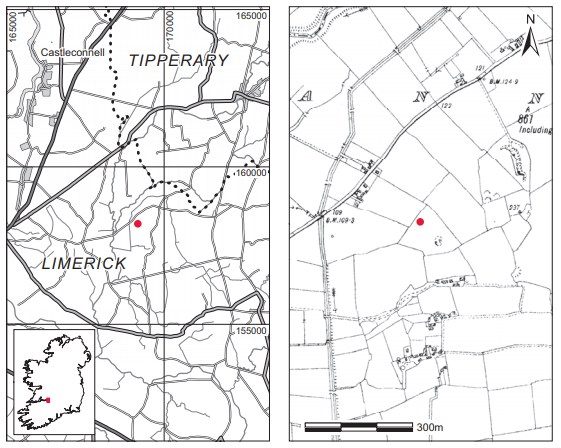

Location (Fig. 2.3)

The site was in the townland of Annagh in north County Limerick, approximately 15km north-east of Limerick City, close to the Tipperary border 5. It was situated between 50m and 60m above sea level on the north-west slope of a hill with views to the north and east. The plain to the west is drained by the Annagh and Newport rivers.

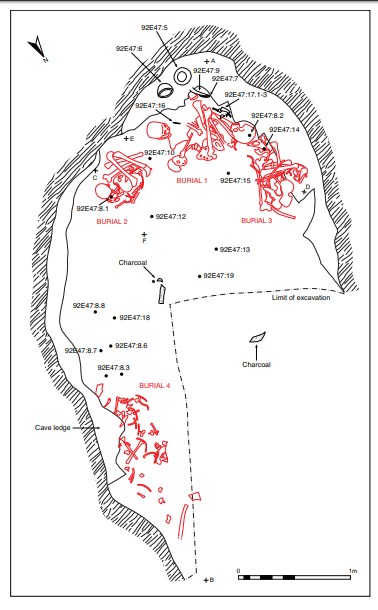

Description of site

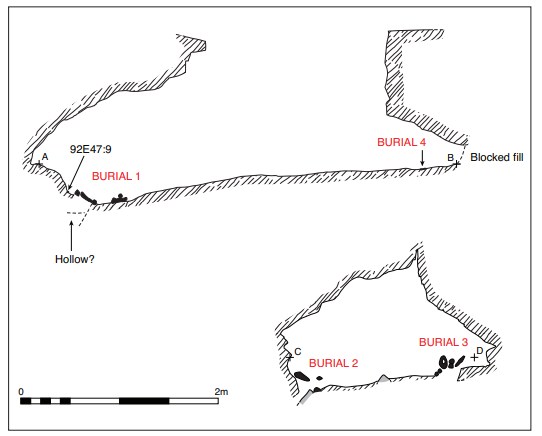

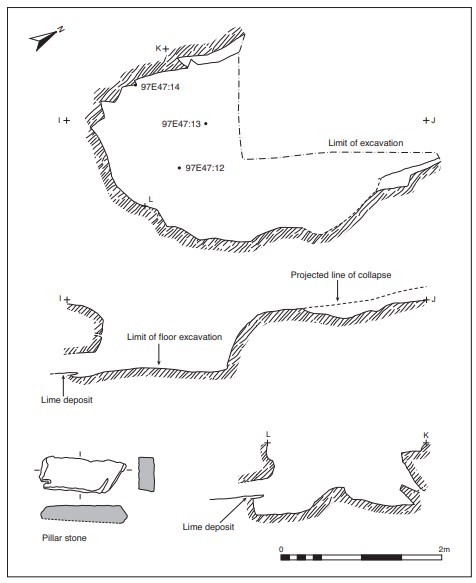

The site consisted of an oval chamber, 4.5m long by 2.5m wide (Fig. 2.4). The cavern had developed along a natural fault line that could be seen in the roof. The entrance had been blocked by a pillar-like slab, 1.02m long by 0.38m wide by 0.22m in maximum width (Fig. 2.9).

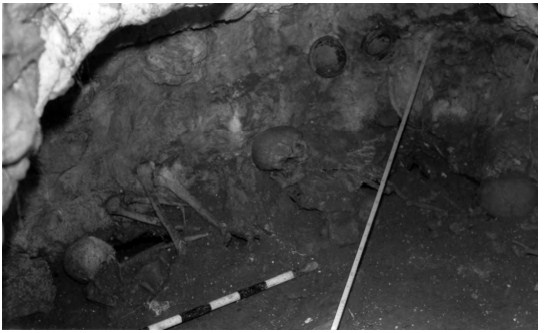

The floor of the chamber sloped from east to west so that the eastern end was obscured (Figs 2.8–2.10). It became apparent that this slope was already present in antiquity because limewash from the roof extended over the sloping fill of the cavern floor and over loose human bone scattered on the surface of the fill along the south side of the cavern, which sloped from east to west. The deepest part of the chamber was at its western end, measuring 1m in height, and it was here that the principal burials occurred. Excavation concentrated on the cave fill immediately below the area where the human bone was found. This consisted of an L-shaped area along the south and west sides of the cavern. During the course of the excavation it was necessary to remove part of the east end of the cavern to gain safe access to the chamber. The fill of the cave was a uniform dark brown loamy clay with stones of varying size up to 0.7m in length.6 Animal bone7 was also noted resting on loose stones, which were covered in limewash. In all, three human burials were recovered and portions of at least two others. All of the remains identified were male. Associated with these burials were two complete vessels, substantial portions of a third vessel and small fragments of a fourth undecorated vessel. Small amounts of cremated bone, some of it human, also occurred in two separate locations. The western side of the cave was excavated to a depth of some 0.7m below the ledge, and on the south side to a depth of 0.7–0.8m below it. Apart from the artefacts associated with the burials, flint artefacts were found below the level of the burials; a flint blade was found in the centre of the cave c. 0.8m east of burial 1 and 0.52m southeast of burial 3, and a flint arrowhead was found c. 0.2m north-east of burial 2, 0.2m below the level of the burials. Some sherds, probably of the same carinated undecorated vessel found with the burials, were also recovered from the central area of the cave.

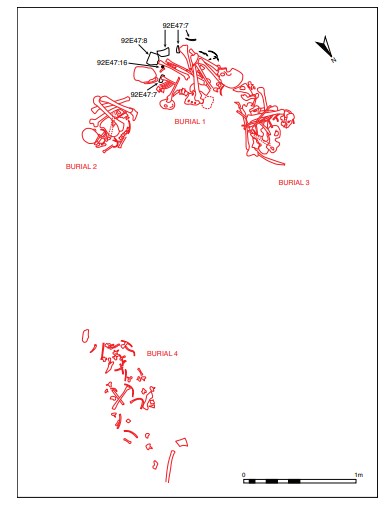

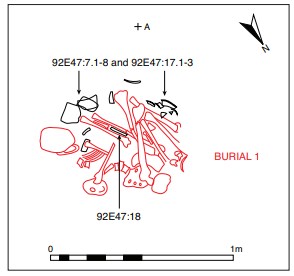

Burial 1, 92E47:1

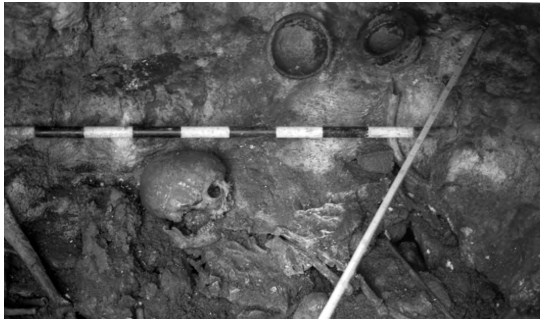

This skeleton was located at the west end of the chamber between burials 2 and 3 (Figs 2.4–6). The remains were those of an adult male, aged 55+ years at the time of death. The burial consisted of a crouched inhumation lying on its left side, the upper portion supine and the knees tightly flexed. The head was located to the south and the feet to the north, close to the skull of burial 3. The arms were flexed and drawn up close to the face. A bone point (possibly sheep bone, 92E47:16) encased in limewash was found underneath the left arm (Fig. 2.13). Incorporated into the limewash, which extended over the whole area of the torso and underneath the body, were substantial sherds of a decorated bowl (vessel 3, 92E47:7; Fig. 2.12), apparently dislodged from its original position, perhaps on the ledge above.

Further sherds, probably of the same vessel, were found at the northern end of the burial underneath the torso and knees.8 These also appear to have fallen from the ledge above, and sherds of the same vessel were found lodged in a crevice in the rock above the knees of the burial. A number of rim sherds of a plain carinated vessel (vessel 4, 92E47:18) were also associated with the burial.9 Two pottery vessels had been placed on the ledge above burial 1, and some burnt sheep bone and a cow’s tooth were found between them. One (vessel 1, 92E47:5) was a decorated necked bowl of Drimnagh type. The second vessel was a decorated globular bowl (vessel 2, 92E47:6) which had been placed to the south. Fused to the vertical face of the ledge between these was a perforated antler tine (92E47:9). Some fragments of sheep bone were identified among the remains.

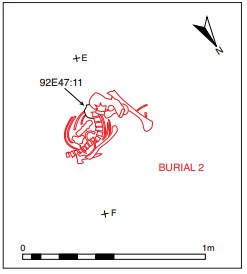

Burial 2, 92E47:2

This was located c. 0.15m south of burial 1 (Figs 2.4–5 and 2.7). The articulated body was tightly crouched and oriented with the head to the south-east. The head was placed face down, with the mandible articulated against the west wall; the knees were flexed and resting against the wall of the chamber. The leg bones were at a significantly higher level in relation to the rest of the body, indicating a degree of settling of the bones. The remains were those of an adult male, who was also aged 55+ years at the time of death. According to Ó Donnabháin (see report below), degenerative changes noted in the upper spine are suggestive of frequent use of the head for carrying loads. A number of fractures were also noted on the skull and ribs. At the base of the spine, underneath the lumbar vertebrae, a discoidal flint knife (92E47:11; Fig. 2.13) was found, and the head of a bone toggle (92E47:10; Fig. 2.13) was recovered ex situ from a ledge immediately north of the burial (Fig. 2.4).10 A large sherd of a plain carinated vessel (92E47:8) rested with the outer surface downwards at the base of the skull between the scapula and the mandible, and another sherd of the same vessel 11 was found in the area of the torso. Some of the animal bone found in association with the burial was identified as pig and hare.

Burial 3, 92E47:3

This was located to the north of burial 1. It consisted of the disarticulated skeletal remains of an adult male, aged at least 30 years at the time of death. The long bones had been placed parallel to one another with the two pelvic bones placed over them at the eastern end. The skull and lower mandible were located at the western end, placed against the ledge on the north side of the cavern, facing south. The ribs were placed over the long bones, in no apparent order. The distal end of the left humerus appears to have been burned as opposed to cremated, but no trace of a hearth was found in the cave. Although the burial was a secondary interment, Ó Donnabháin suggests that the remains may have been positioned in such a way as to mimic the position of the articulated skeleton. A flint flake was found c. 0.25m below the northern end of the skull, and a stone pebble was recovered c. 0.26m east of the skull and 0.14m south of the ledge. Animal remains found with the burial include pig, sheep, cow, bear and possibly wolf.

Burial 4, 92E47:4

This consisted of a scatter of the disarticulated remains of at least two individuals, both probably male, together with a small number of animal bones mixed in with them (see Ó Donnabháin, p. 44) (Figs 2.4–6 and 2.8). The deposit covered an area 0.6m long by 2.5m wide along the south-eastern side of the chamber, almost 2m from burials 1–3, lying on the sloping fill of the floor. The bones consisted largely of vertebrae, ribs, scapulae and other small joint bones, along with two or three small long bones and a mandible. Neither long bones nor a skull were found. In and around these bones were small, thumbnail-sized sherds of a coarse undecorated pottery vessel (Fig. 2.4) similar to sherds associated with burial 2. The edge of the cavern in this area consists of a vertical face on top of which was limewash mixed with bones. This extended over the fill, suggesting that the bones were placed on the fill and were later incorporated into the limewash, which extends over the fill. The remains of pig, hare,

bear (radius) and sheep were identified within the deposit, some having been placed on a rock ledge adjacent to the human bone.

Cremated bone

Two pieces of burnt bone, possibly human, were recovered from a point about midway along the south wall of the cavern beside the bones of burial 4. In addition, some blackened human bone was uncovered on the ledge at the western end of the chamber between vessels 1 and 2, associated with a number of unburnt animal teeth.

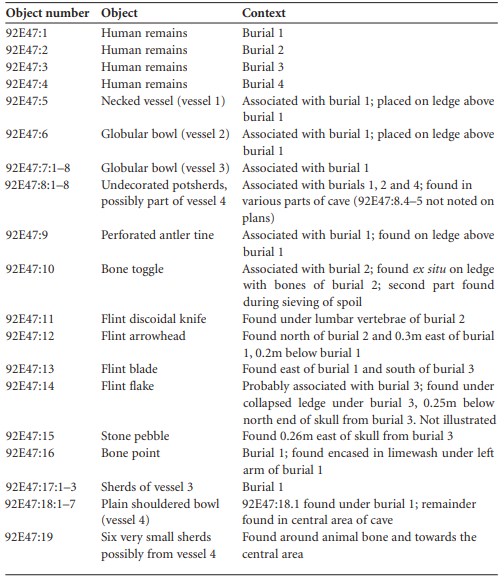

The finds (Figs 2.11–13; Table 2:2)

Ceramics

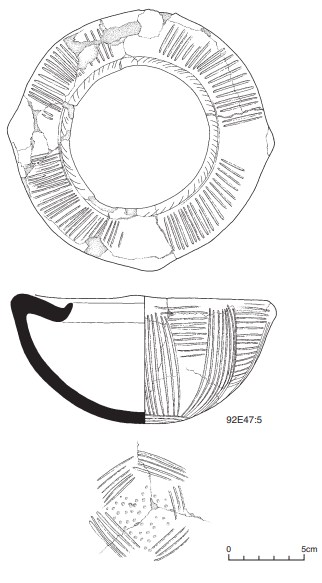

Two complete vessels and fragments of two others were found in the course of the excavation. 92E47:5 (Fig. 2.11) is an almost complete (conserved and restored) vessel of classic Style 1 Necked Vessel A type, according to the typology developed for decorated Neolithic pottery by Herity (1982, 268–9). It has a slanted rim, wide neck and rounded body.

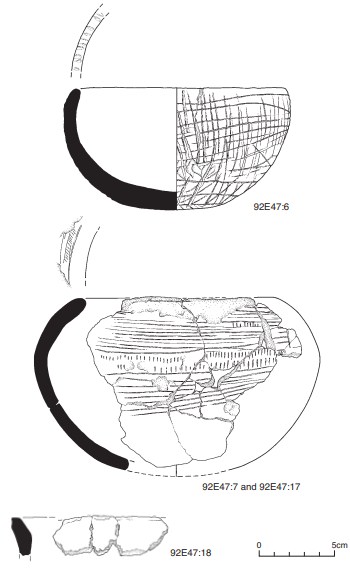

Three of four imperforate lugs survive. The rim is slanted slightly inwards and is decorated with irregularly spaced short incised grooves. The neck is decorated with four panels of shallow grooves, varying from straight to slanted lines, which are grouped together between the lugs—the areas corresponding to the width of the lugs being left undecorated. The decoration on the body comprises sixteen panels of lines alternating in bands of horizontal and vertical grooves. The horizontal panels cover about one third of the upper body. The vertical lines follow the outline of the body towards the base. The basal area is outlined by five panels of horizontal grooves forming an approximately lozenge-shaped outline to the base. The ‘base’ is decorated with an irregular pattern of circular impressions. This surface is very worn. Dimensions: H 8.5cm; max. ext. D incl. lugs 17.4cm; int. D of rim 9.4cm; W of neck 2.5–3cm. The vessel is of Drimnagh bowl type and is closest in style to the bowl from Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow (Herity 1982, 315). 92E47:6 (Fig. 2.12) is a complete globular bowl of the type referred to as Goodland bowls (Herity 1982, 275). The rim is rounded. The vessel is very dark in colour with very large grits. Both the internal and external surfaces are burnished. The decoration consists of an all-over lattice pattern that is quite irregular in places. Some of the vertical lines start on the rim of the vessel but this is not continuous. Dimensions: H 8.4cm; int. max. D 15cm; D of rim 12.8cm; ext. D of rim 14.3cm. 92E47:7.1–8 and 92E47:17.1–3 (Fig. 2.12) consist of a number of sherds which originate from a globular bowl. The sherds are decorated with a pattern of horizontal grooves occasionally interspersed with rows of short vertical strokes. The rim is slightly rounded. Approx. dimensions: H 12cm; max. ext. rim D 13cm. This bowl is similar to one of the Rockbarton (Cahirguillamore), Co. Limerick, vessels (Herity 1982, 311, fig. 25, 3). 92E47:18 (Fig. 2.12): a number of small sherds from a plain shouldered bowl.

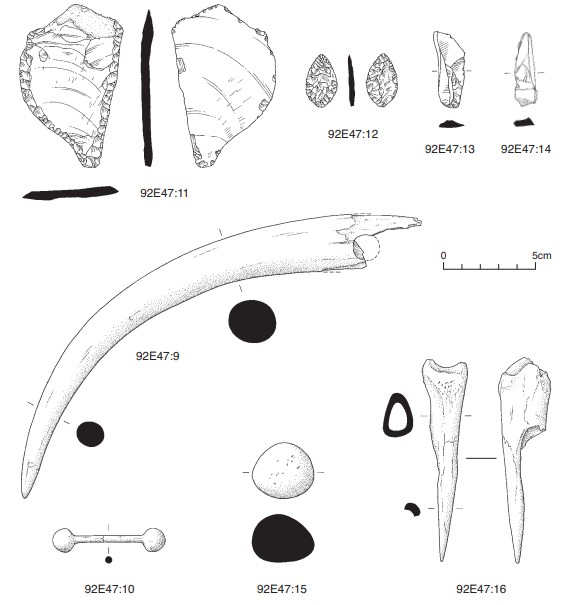

Bone (Fig. 2.13)

92E47:9 is a length of perforated antler tine found on the ledge above burial 1. It has a very smooth, polished appearance. It is damaged at the wider end and has fractured across the perforation that was present on one face. Dimensions: L of outer curve 30cm; L of inner curve 24cm; max. D 2.9cm by 2.5cm (undamaged surface); D of perforation c. 1.4cm. 92E47:10 is a bone barbell toggle in two fragments. The pin is circular in section. The heads of the toggle are of poppy-head form. This is a variant amongst the types of heads known for these pins, which include also conical and mushroom-headed forms. Dimensions: L (both fragments) 6cm; max. D of poppy head 1.28cm by 1cm; H of head 1.3cm; av. D of pin 0.34cm. 92E47:16 is a bone point made from a fragment of a long bone worked to a point (tip lost). Dimensions: L 10.85cm; max. dimensions at top 2.76cm by 2.55cm. Similar bone points have been found at Rockbarton (Cahirguillamore), Co. Limerick, and Baunogenasraid, Co. Carlow (Herity 1982, 256, fig. 17, 3; 312, fig. 26, 9).

Lithics (Fig. 2.13)

92E47:11 is an unusual heavily patinated flint12 artefact of approximately semicircular form. It has been retouched along the straight edge and along the major portion of the curved edge. There is a slight tang-like extension on one side where the two sides meet. The function of this object is not clear. The extended end is worked but not pointed. It may be a form of discoidal knife. Dimensions: 8.5cm by 5.2cm by 0.5cm. 92E47:12 is a leaf-shaped, heavily patinated flint arrowhead with a very slight tang. Dimensions: L 2.8cm; W 1.7cm; T 0.35cm. 92E47:13 is an unretouched, heavily patinated flint blade. Dimensions: L 4.2cm; max. W 1.5cm; T 0.4cm. 92E47:14 is a narrow, pointed flint flake. There is no evidence of retouch and some accretions are visible on the surface. The stone appears to be laminated on the ventral surface on one side and flake scars are visible on its dorsal surface. Dimensions: L 3.99cm; W 1.19cm; T 0.49cm.

Comment

The pottery vessels from the site are closely comparable to those found in fourth-millennium Linkardstown-type cists. In particular, the necked bowl can be compared with the bowls from Drimnagh, Co. Dublin, Lisduggan North, Co. Cork, and Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow. It combines elements of the typology of the bowls related to Drimnagh but decoratively is closer to Ballintruer More. The globular bowls find their closest comparisons both stylistically and geographically in the bowls from Rockbarton (Cahirguillamore), Co. Limerick. There are also close analogies between the grave-goods as a whole, as the bone point and the barbell toggle are also paralleled at Rockbarton. The placement of objects—sherds of Beaker pottery and a flint scraper—on a ledge above the burial deposits was also noted at Rockbarton. Although there are very few details recorded about the disposition of the burials at Lisduggan North, the site was also a natural cavern or rock fissure. At Ashleypark, Co. Tipperary, a natural limestone feature was modified to produce a pseudo-megalithic structure, as mentioned above. It is notable that at these four sites in north Tipperary, east Limerick and north Cork people did not construct burial cists proper but, in various ways, used naturally occurring features. This is partly due to the local topography, in which caves, caverns and fissures are available, but there is almost certainly an element of special selection of these dark, closed-off spaces in which to bury the dead. The discovery of human and animal remains in a cave system at Killuragh, Co. Limerick, that has also been dated to this period of the Neolithic (Woodman, forthcoming) is a further indication of the attractiveness of these places. Although Lisduggan North is the most southerly, together the sites noted here form a special group united by their particular settings.

In his osteoarchaeology report below, Barra Ó Donnabháin has identified the remains of at least five individuals, all mature males, two of whom would be regarded as elderly for the period. Their skeletons exhibited evidence of hard physical work, including the carrying of heavy loads. While the skeletons comprising burials 1 and 2 were intact, the skeletons of burials 3 and 4 were disarticulated. This means that these bodies had been allowed to decay to the stage where the bones were disconnected. Where this process took place is not known, nor is it known why the bodies of some individuals were treated in this way while others were buried in what appears to be a single act. Ó Donnabháin also suggests that there is sufficient evidence of similarity between these individuals to indicate that they were related to one another, perhaps members of the same family or kin group. Deposited with the skeletons were four pottery vessels, bone and flint artefacts, together with animal bone. The bowls must have represented a considerable part of the wealth of this community. It is also clear that the female and younger members of these families were not ‘admitted’ to the cave for burial purposes. Many possible explanations might be put forward for this practice of exclusion, but they would be entirely speculative in the present state of knowledge about how Neolithic communities interacted with one another and with their environment.

Dating

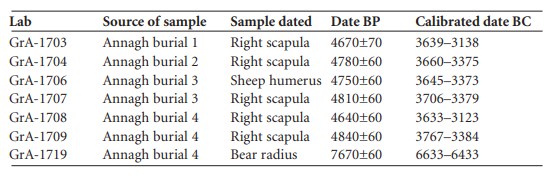

Seven radiocarbon dates from human (five samples) and animal bone (two samples) are available for this site, as detailed in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1—Radiocarbon dates, Annagh, Co. Limerick.

With the exception of the sample from the bear, which is clearly of much earlier date than the burials, the dates from Annagh show a reasonably tight group, which suggests that the cave was used for burial either on a single occasion or over a short period. The necked bowl from Annagh is very similar to the pottery from a number of other Linkardstown-type sites, whether cists or natural features. Brindley and Lanting (1990, 5, fig. 2) show that this type of bowl dates from the intermediary period in the development of the typology of these vessels, which they date to about 3520–3450 cal. BC. As just two samples of animal bone were dated, it is not possible to say whether the other species identified in the cave are all contemporary with the burials. It is possible that some, like the bear, are older or, indeed, much younger. Nevertheless, it does seem likely that the boar and sheep may represent food waste while the presence of hare may be fortuitous.

Conclusion

As is so often the case for burials of this type, this site was discovered accidentally during quarrying work. The excavation was conducted in extremely difficult circumstances owing to the confined nature of the cavern. The retrieval of the artefacts, especially the vessels, required special recovery techniques because the pottery had become fixed in situ over the millennia by the lime-rich water that was present in the cave. Its importance is underlined by the nature of the burials and the accompanying material. Annagh is one of a group of burials of early Neolithic date closely related in terms of date, burial rite and accompanying grave-goods, known generally as ‘Linkardstown cists’, which occur in the southern half of Ireland from the northern parts of County Cork across country to counties Meath and Dublin. Lisduggan North is the most southerly and westerly site identified to date, while the most easterly and northerly locations are at Chapelizod and Drimnagh, Co. Dublin. Annagh and the related sites mentioned above in counties Cork, Limerick and Tipperary differ in that they are located in natural subterranean or enclosed settings rather than in constructed cists covered by mounds. In this way the essence of entombment was achieved using natural elements of the regional geomorphology as a substitute for the built structures of the east.

List of finds

Table 2.2—List of finds, Annagh, Co. Limerick.

HUMAN REMAINS

BARRA Ó DONNABHÁIN

Introduction

The cave contained three mostly complete skeletons and a scatter of loose bones. The latter contained the remains of at least three individuals. It is possible that some of the elements in the loose scatter originally came from the three adjacent skeletons. A minimum number of individuals count per bone was carried out for the entire collection. Four discrete skeletal elements occurred five times (right scapula, left second metacarpal, right calcaneus and lumbar vertebrae), indicating that the deposit in the cave represents the remains of at least five individuals. All were adults and all appear to have been males. Some fragments of animal bone were found with each of the four groups of human bones. Two pieces of burnt bone were recovered from a point about midway along the natural rock ledge along the south wall of the cavern, adjacent to the loose jumble of bones (burial 4). These were fragments of animal bone.

Burial 1 (92E47:1) x

This skeleton was found against the west wall of the cave in a tightly flexed position. The body had been placed lying on its left side with the head to the south and had eventually been covered in lime deposits derived from the walls of the cave. Parts of the skull and the upper portion of the thorax were embedded in the solidified lime deposits and have yet to be extracted from this. Apart from this embedded material, all major skeletal elements were recovered. Some small bones from the feet of another individual were found with this skeleton. These bones may have come from burial 3. A few small fragments of animal bone were also found with the skeleton.

Age and sex

The secondary sexual characteristics of the pelvis, cranium and mandible indicate that this was a male. The morphology of the pubic symphysis suggests that this was an older adult who was probably aged 55+ years at the time of death.

Stature

Application of the regression equations developed by Trotter and Gleser (1952; 1958) for the estimation of maximum living stature from skeletal remains suggested that this individual would have been about 170cm tall.

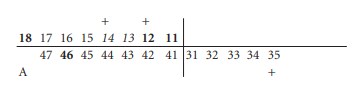

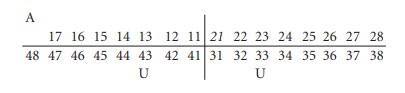

Teeth

The state of the dentition is summarised in the chart below. In the dental charts in this report, tooth positions that are blank indicate that the particular portion of alveolar bone was not available for inspection; teeth in italics were missing post-mortem, while teeth in bold were lost ante-mortem. A plus (+) sign over (maxillary) or under (mandibular) a tooth position indicates the presence of a chronic dental abscess, while the letter A indicates that the tooth was probably congenitally absent. The upper left and the distal portion of the lower left quadrants were not available for inspection, as they remain embedded in the cave deposits.

Moderate amounts of calculus are present on the surviving anterior teeth, while the distal teeth have small deposits or none at all. A chronic dental abscess occurs at the right maxillary first molar, while periapical cysts are present at the roots of the upper right lateral incisor and the lower left second premolar. It seems likely that the evidence for chronic abscess, periapical cysts and ante-mortem tooth loss is related to very heavy dental attrition. Secondary dentine has been exposed on all occlusal surfaces but this wear is quite uneven. This irregular wear was caused by the loss of the upper anterior teeth. Once these teeth had been shed, attrition was heaviest on the buccal sides of the occlusal surfaces of the lower premolars and the molars, while in the maxilla wear was concentrated on the lingual sides of the occlusal surfaces of the corresponding teeth. Both the upper and lower right second premolars are worn to uneven root stumps, while the lower right second molar is also worn to a root stump (Pl. 5).

Most of the enamel of the upper right first molar has been worn away and secondary dentine has been exposed over the entire occlusal surface of the tooth. There is a shallow, Vsectioned groove on the buccal side of the tooth. The shape and polished nature of this groove suggest that it was produced by a habitual activity such as regularly pulling a small hard object along the buccal edge of the tooth.

Pathology

This individual suffered from a mild degree of degenerative joint disease—osteoarthritis—in the right shoulder, right elbow, right thumb and both knees. Degenerative joint disease was also found in the vertebrae. This was more severe in the posterior joints of the neck and upper back, especially on the right side.

Burial 2 (92E47:2)

This skeleton also lay against the west wall of the cave, immediately south of burial 1. The position of the body was similar to that of burial 1; the skeleton was tightly flexed, with the knees resting against the wall of the chamber. This cadaver had also been placed on the cave floor, lying on its left side with the head to the south. The skull had become covered with a lime deposit. This was removed where possible. As was the case with burial 1, some commingling of remains had occurred. The few extra bones may have come from any of the other complete skeletons. A few small fragments of animal bone were also found with this burial.

Age and sex

This was clearly the skeleton of a male. The morphology of the pubic symphysis and the presence of an ossified thyroid cartilage indicate that this individual was also an older adult at the time of death, i.e. 55+ years old.

Stature

Using the Trotter and Gleser (1952; 1958) formulae, a maximum living stature of about 166.5cm was obtained for this individual.

Teeth

The entire permanent dentition was present in the jaws at the time of death. The four central incisors were lost post-mortem, however, and were not subsequently recovered. None of the teeth had caries and there were no chronic dental abscesses. Bone defects due to periodontal disease were noted around the lower left first molar. When the cave deposit was being removed from the teeth, many of the calculus deposits remained attached to the limestone. Nevertheless, it was still possible to see where the calculus deposits had been: moderate amounts of calculus occurred on all teeth except for the anterior, maxillary dentition, where there was none. The latter teeth had suffered from a severe degree of dental attrition and this may have prevented calculus build-up. Attrition was heavy and the uneven distribution of wear was very similar to the pattern seen in burial 1. Attrition was heaviest on the maxillary anterior teeth in the area between the first premolars. These later teeth had the most uneven attrition, while the more mesial teeth were worn to flattened stumps that were almost flush with the alveolar bone (Pl. 6).

Pathology

This individual suffered from degenerative joint disease in both shoulders and in the right elbow. The arthritic changes in each of these joints were mild. Arthritic degenerative lesions were also encountered in many of the vertebrae and in many of the costo-vertebral joints. The vertebral lesions were mostly confined to the posterior joints, almost all of which were affected. The lesions were mild in the lumbar and thoracic regions of the spine but were severe in the neck. The second and third cervical elements were fused by these degenerative changes. The distribution and severity of the lesions are suggestive of the habitual use of the head for carrying loads (Pl. 7).

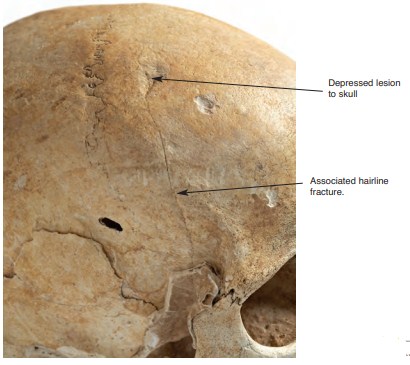

This skeleton had a number of healed fractures. The most severe and potentially dangerous of these lesions was a depressed fracture on the lateral side of the right frontal, located just 10mm anterior to the coronal suture (Pl. 8). The depressed area is ovoid, measuring 16mm by 10.5mm, with its long axis along the coronal plane. Secondary cracking—also healed—extends caudally from the most inferior point of the depressed lesion. This hairline fracture extends for at least 60mm in a straight line parallel to the coronal suture. Unfortunately, in the region of pterion, the fracture is obscured by the adhering limestone. The inner table bone was not affected by either of these wounds. The depressed fracture was probably caused by a blow from a small, blunt object such as a stone. This blow must have been delivered with considerable force to produce the associated hairline fracture. These wounds probably resulted in some degree of loss of consciousness and perhaps concussion, but the degree of healing observed indicates that they were not fatal.

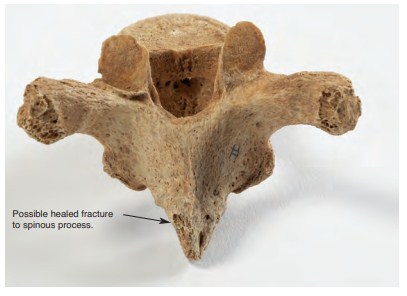

This individual had at least three other fractured bones. One unsided rib fragment had a healed fracture in the body of the bone (Pl. 9). Most accidental rib fractures—resulting from mishaps such as a heavy fall on the chest—tend to occur at the angle or in the posterior portion of the bone (Crawford Adams 1983). Wells (1982) remarked that a fracture occurring in the body of the rib, as in this case, tends to be the result of a direct blow to the chest. The other two healed fractures occur on the spinous processes of the fourth or fifth thoracic vertebra (Pl. 10). These injuries may be related to the carrying of heavy loads on the upper back.

Burial 3 (92E47:3)

This disarticulated, secondary interment was found immediately north of burial 1. The skull lay adjacent to the feet of the latter individual and the two extra metatarsals recovered

probably came from that skeleton. The remains are those of one individual. All major skeletal elements were present. The skull lay at the southern end of the disarticulated spread. The two hip bones lay at the opposite end of the collection of bones. Both femora and the left tibia lay in a parallel row between the skull and hip bones. The right tibia, right humerus and the proximal end of the left humerus lay perpendicular to the other three long bones. This pattern may be an attempt to mimic the flexed position of the articulated skeletons.

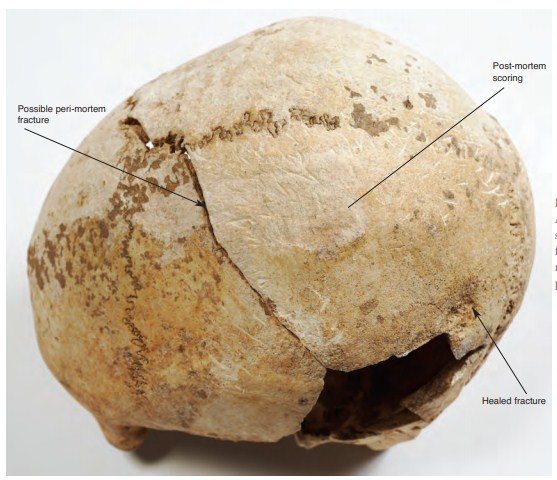

Only a portion of the proximal end of the left humerus was found. The distal end of this fragment was burned. This was not cremated per se but had been burned at some time after the body had already become skeletonised (Pl. 11). There were no traces of a hearth or any other evidence that burning had taken place inside the cavern. The cranium was broken in two halves across the coronal plane, immediately posterior to and along the coronal suture (Pl. 12). From the position of the skull it would appear that this break occurred in antiquity, as a coating of lime had developed on the broken surfaces of the bone.

Some fragments of animal bone were also found with this collection of bones.

Age and sex

This skeleton was also clearly that of a male. The morphology of the pubic symphysis suggests at least a middle-aged adult and maybe an older adult. It seems likely that he was at least 30 years of age at the time of death and may have been older.

Stature

Application of the Trotter and Gleser (1952; 1958) equations produced an estimate of 175cm for the living stature of this individual.

Teeth

The state of the dentition is summarised in the chart below. The letter U above (maxillary) or below (mandibular) the tooth indicates that the tooth was present but unerupted, while the letter A in such a position indicates that the tooth was congenitally absent.

The upper right third molar appears to have been congenitally absent, while both of the lower canines were present in the mandible but had not erupted. These are both relatively common dental anomalies.

None of the teeth had caries and there were no chronic dental abscesses. There was a moderate amount of calculus on the premolars and molars, whereas the deposits on the anterior teeth were small. Bone defects produced by periodontal disease were noted around the lower left third molar.

The degree of dental attrition was heavy in comparison with modern western populations but was not as severe as that found in burials 1 and 2. The pattern of wear also differed from that encountered in the other two skulls. Secondary dentine was exposed on the occlusal surfaces of all the incisors and maxillary canines (the mandibular canines had not erupted). Pockets of secondary dentine were exposed on the premolars and all of the molars, except for the upper right third. The wear on the latter was confined to the enamel. In the jaws of this individual, tooth wear was much more evenly distributed throughout the dental arcade than was the case with burials 1 and 2. The anterior teeth had not suffered the excessive attrition seen in the latter individuals and the crowns remained relatively intact (Pl. 13).

Pathology and anomalies

This individual suffered from degenerative arthritis in a number of joints. Both shoulders, both elbows, the left hip, the right wrist and the right ankle all had evidence of mild degenerative changes. The acromio-clavicular joints of both shoulders had moderately severe lesions. Many of the vertebrae also had evidence of degenerative joint disease. This was quite severe in the joints of the lower neck.

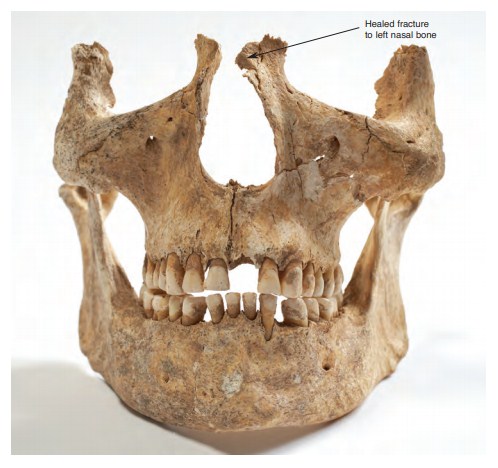

This person also had a number of healed fractures. The lower portion of the left nasal bone had been broken (Pl. 13). The adjacent portion of the right nasal was not recovered. The fracture had healed but probably resulted in some deformation of the nose.

A potentially more serious wound was found on the left parietal, 20mm anterior to the lambdoid suture. This is a circular depressed fracture on the outer table bone alone (Pl. 12). The depressed area has a diameter of 23.5mm. There is a 35mm-wide band of osteitis superior to the wound. This was presumably the result of a soft tissue infection that set in after the initial lesion was incurred. Unfortunately, the area of the skull immediately anterior to the fracture was broken post-mortem (or possibly peri-mortem) and was not recovered. The depressed fracture and soft tissue infection had healed before death occurred. This wound was caused by a small blunt object, probably similar to the one that caused a comparable injury to the frontal of burial 2.

This skull lay on the cave floor on its left side. It was not covered by soil and was not damaged in any way during its recovery. A thin layer of lime had built up on the exposed portion of the cranium. When it was washed, the lime deposit came away in large plaques. The underlying surface of the skull was found to have about 150 small scratches or scores (Pl. 12), apparently confined to the surface that lay exposed in the cave and concentrated on the right parietal. These marks also occur on the occipital in the region of lambda, on the left parietal between the saggital suture and the temporal line and on the right portion of the frontal, extending as far as the frontal boss (Pl. 14). Some of these marks are deeper than others and look very fresh, even though they could not be so. They are not the result of rodent gnawing but rather seem to have been inflicted with a sharp cutting instrument. There is no discernible patterning in the scoring, though many of the scratches form groups of roughly parallel lines. The latter detail might be suggestive of the activity of a clawed animal, but the marks are not equidistant, they are not of equal length and they do not occur in groups of four or five. On the left parietal there is a group of ten roughly parallel lines perpendicular to the edge of the post-mortem (or peri-mortem) breakage of the skull. These cuts do not continue on the bone at the other side of the breakage and may therefore post-date this cracking of the bone. One other mark similar to those found on the skull was found on the posterior portion of the left condyle of the mandible.

This skull is from the disarticulated skeleton of one individual. The bones of the rest of the skeleton had none of the cut marks characteristic of deliberate defleshing. Similarly, the marks on the skull do not appear to be the result of an activity such as scalping. Only a few straight cuts are necessary for the latter process, as the scalp can easily be reflected off the bone once the initial incision has been made. Moreover, the scoring seems to have been done after the skull lay in its final burial position.

Burial 4 (92E47:4)

This consisted of a jumble of disarticulated bone scattered over a 60cm-wide area along the southern side of the chamber. The remains were mostly human, though a small number of animal bones were mixed with these. The human bones were all from the skeletons of adults and included 29 vertebrae from at least two individuals, both probably male. These could not have belonged to the other three burials in the cavern. The cranial remains in the disarticulated scatter consisted of a complete mandible, which was also probably that of a male. The larger post-cranial bones in the loose jumble included three scapulae (one left, two right), two clavicles (one left, one right), the distal end of a left humerus, a left radius, a right ulna, three patellae (two left, one right) and portions of at least twenty ribs (ten left, ten right). Many of the smaller bones of the hands and feet were also present. The minimum number of individuals in this jumble of bones was three.

Teeth

In the one mandible recovered, all but one of the teeth were present in the occlusion at the time of death. The lower right central incisor had been lost a considerable time before death. The lower right canine was lost post-mortem. All of the teeth had small deposits of calculus except for the third molars, which had larger deposits on their lingual surfaces. None of the teeth had caries, but there were areas of bone loss indicative of periodontal disease around the lower left first premolar and lower right second molar. The distribution and severity of dental attrition were reminiscent of the patterns seen in burials 1 and 2 rather than those seen in burial 3. Wear was heaviest on the anterior teeth, concentrated on the right side. The right lateral incisor had been worn to a root stump, while a 2mm depth of enamel survived on the left central incisor. The wear on the premolars and molars was concentrated on the buccal aspects of the occlusal surfaces of those teeth. Similar patterns in burials 1 and 2 seemed to be related to the loss or extreme attrition of the upper anterior teeth. The root stump of the lower right lateral incisor was rounded in a way that could not have been the result of tooth-on-tooth contact. The tooth had been abraded by regular contact with some relatively soft material that was pulled through the teeth. Similarly, grooves on both the mesial and distal sides of the buccal surface of the lower left first premolar were not the result of tooth-on-tooth wear but were suggestive of the habitual use of the tooth as a cutting instrument for some fine, thread-like material.

Pathology

Of the three scapulae recovered from this disarticulated spread, two (one left, one right) were mildly arthritic. Differences in size indicated that these came from the shoulders of two different individuals. Many of the 29 vertebrae recovered from the disarticulated spread had degenerative changes. One second lumbar vertebra was slightly compressed and the margins of the centrum had severe osteophytosis. The same individual had very large Schmorl’s nodes in the bodies of the first and second lumbar vertebrae. These latter defects are caused by the herniation of the gelatinous core of the intervertebral disc, and these lesions and the compression of the centrum probably relate to a single traumatic incident that occurred in adolescence or early adulthood, as the core of the disc solidifies later in life. The osteophytosis may have been part of the degenerative sequelae of this injury.

Discussion

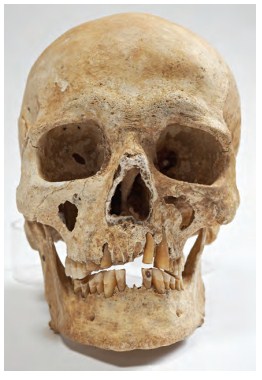

The cavern at Annagh contained the mostly complete skeletons of three adult males and small portions of at least two other individuals, who were probably also adult males. A few fragments of animal bones were found with each of the four discrete groups of human remains.

Of the three more complete skeletons, two were primary interments whereas the third was a secondary deposit. The two primary burials (1 and 2) had been placed adjacent to one another in a similar body position, i.e. lying tightly flexed on their left sides, with the skull to the south and the knees to the west. The third mostly complete skeleton was not in correct anatomical position and had clearly been allowed to decay elsewhere before being placed in the location in which it was found. The bones had been laid in an arrangement that may reflect an attempt to recreate or mimic the body position of the crouched primary burials. The skull lay at the southern end of the bone spread, while the hip bones lay at the opposite end. In between lay three long bones, and three other long bones had been laid perpendicular to these.

Even though burial 3 was clearly a secondary deposit, all major body parts were present, except for one vertebra as well as the left clavicle and radius and the right fibula and patella. Most of the bones of both feet were present, though the hands were represented by only two left carpals. This was a comprehensive and relatively efficient gathering of the remains of this person, as the skeleton is as complete as those of the individuals whose bones still lay in articulation. It implies that a considerable degree of care was taken with the original deposition of the cadaver, as well as with the subsequent retrieval of remains. Indeed, the degree of completeness of the skeleton might even suggest that the cadaver was allowed to decay within this cave and that the bones were later carefully collected and rearranged into the position in which they were found.

All of the remains appear to belong to adult males. Two of the more complete skeletons had probably reached their sixth decade at least by the time of death. The third was at least in his fourth decade. These three individuals had a mean stature of 170.5cm. This is similar to the average stature of 38 sixteenth-century males from Tintern Abbey, Co. Wexford (Ó Donnabháin 2010), and very close to the mean stature of a very large sample of modern Irish males measured in the 1930s (Hooton and Dupertuis 1955).

Considering that at least two of these individuals survived to quite an advanced age, the dental health of the group could be described as being generally good. Tooth decay was not found, there was little ante-mortem loss of teeth and calculus was not a major problem. The absence of caries is not surprising. The Neolithic population at Poulnabrone, Co. Clare, had a caries rate of just 0.2% of the permanent teeth recovered (Lynch and Ó Donnabháin 1994). Dental attrition and abrasion, however, were the major dental problems and were probably the cause of all ante-mortem tooth loss in this sample. Excessive wear was also related to each of the cases of chronic abscess and periapical cyst and to some of the incidents of periodontal bone defects. Some of this wear was probably related to diet: a relatively coarse diet would have a cleaning effect that would have helped reduce calculus deposition. Nevertheless, the excessive wear patterns seen in the anterior maxillary teeth in two of the three maxillae recovered are suggestive of abrasion caused by the habitual use of the teeth as a tool rather than the attrition produced by tooth-on-tooth contact during the chewing of food. The difference in the wear patterns between burial 3 and burials 1 and 2 may be a function of age. Burial 3 may have been considerably younger than burials 1 and 2. Of course, this disparity might also reflect different activity patterns during life. Many societies have divisions of labour that reflect factors such as gender, age, physical prowess and other determinants of perceived social status.

Degenerative joint disease is essentially an age-related condition. It reflects the cumulative effects of the minor biomechanical stresses and strains incurred in the pursuit of everyday activities. As such, the distribution and severity of the disease can reflect not only the hazards of longevity but also the pattern of mundane activities that an individual engaged in during life. The distribution of arthritic changes in the non-vertebral joints suggests that these men led vigorous, physically active lives. This is hardly surprising given our knowledge of Neolithic subsistence patterns, wherein the majority of groups are envisaged as having had a mixed economy of crop husbandry and stock-rearing augmented by activities such as hunting, fishing and food-gathering. If this was the lifestyle of these people, their degenerative changes are not particularly severe given that the sample includes at least two individuals who survived to fairly advanced ages.

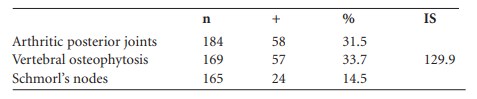

Table 2.3—Frequencies and severity of vertebral pathology.

n = number of hemivertebrae available for inspection.

+ = number of hemivertebrae with lesions.

% = percentage of hemivertebrae with lesions.

IS = index of severity of vertebral osteophytosis.13

The pattern of vertebral pathology is more enlightening. These data are summarised in Table 2.3. In general these rates are not particularly high, considering that the sample is skewed towards the upper end of the age range, and are less severe than those encountered among the late medieval/early post-medieval group buried at Tintern Abbey (Ó Donnabháin 2010). This might suggest that the everyday activities of the Neolithic men buried at Annagh were less strenuous and, in particular, involved less lifting and carrying of heavy weights than did the everyday activities of their medieval descendants. The rates from Annagh are more interesting when broken down according to different spinal regions, as seen in Tables 2.4 and 2.5. The most remarkable features of these data are the degrees of involvement and severity of lesions seen in the neck and upper back. These are highly suggestive of pathology related to a specific activity pattern, such as the transporting of heavy loads using the head, neck and upper back. The distribution of degenerative changes is suggestive of activities such as the direct placing of loads on the head and the carrying of weights on the upper back supported by a strap that was worn around the forehead, such as was done in Ireland with creels into the early twentieth century. These activities would require that the neck be held rigid. Force would be transmitted through the cervical vertebrae and would be maximal at C7 and T1. The regular portage of loads on the upper back with a forehead strap would also account for the costo-vertebral involvement seen in these skeletons, and perhaps for the possible fractured spinous processes of the fourth and fifth thoracic vertebrae of burial 2. All of the other fractures observed—the head wounds of burials 2 and 3, the broken nose of burial 3 and the fractured rib of burial 2—seem likely to have been the result of interpersonal violence. Both head wounds could have been caused by small projectiles such as a stone. In the case of burial 2, this was delivered with considerable force and caused significant though not lethal secondary cracking of the skull. The form of the projectile and the force with which it was delivered might suggest that it was fired from a weapon such as a slingshot.

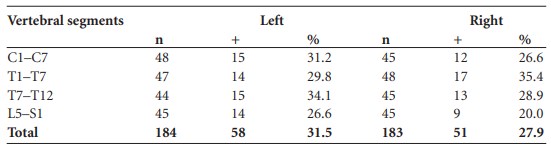

Table 2.4—Frequencies of arthritis on left and right posterior vertebral joints.

n= number of hemivertebrae available for inspection.

+ = number of hemivertebrae with arthrosis.

% = percentage of hemivertebrae with arthritis.

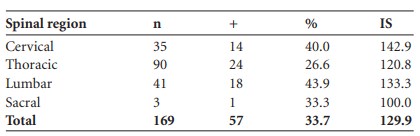

Table 2.5—Indices of severity of vertebral osteophytic lipping.

n = number of hemivertebrae available for inspection.

+ = number of hemivertebrae with lesions.

% = percentage of hemivertebrae with lesions.

IS = index of severity of vertebral osteophytosis.

Two individuals, burials 1 and 3, had congenitally absent third molars. The incidence for this anomaly among modern groups is between 0 and 20%. While the sample from Annagh is obviously too small for a conclusive study of biological distance, the group shared many less than common epigenetic traits. The latter are normal variations in bone architecture that are both genetic and environmental in origin. Burials 1 and 4, for example, shared very similar expressions of complete mylohyoid bridging, a relatively uncommon trait. Burials 1, 2 and 3 had similar acetabular creases, while two of the individuals represented in burial 4 and burial 3 had double anterior calcaneal facets. The similarity in the distribution of these traits may simply reflect responses to virtually identical environmental stimuli during ontogeny and development, but they could also reflect a higher than usual degree of consanguinity among the individuals recovered from the cave. This is perhaps not surprising in a society where a relatively low population and dispersed rural settlement would militate against major gene flow. The possible presence of somewhat fractious neighbours as suggested by the distribution of healed fractures may also have favoured the maintenance of a more restricted gene pool!

The skull and mandible of burial 3 exhibit many shallow incisions. A natural process such as rock exfoliating from the cave roof would not have left a myriad of incised lines, many of them roughly parallel. Such a process would also have left its imprint more generally in the remains. Animal activity seems equally unlikely. The scorings are not teeth marks but, at a glance, do resemble claw marks. They do not, however, occur in the regular numbers at the regular intervals that would be expected if this had been the case. Moreover, there is no evidence that the cave was the lair of some animal after its use during the Neolithic: the primary burials were relatively undisturbed when the site was found, and there was none of the characteristic food debris of a clawed carnivore. While these markings do not seem to relate to behaviour such as scalping or defleshing, they do seem to be an artefact of human activity. The motivation for this remains obscure but may relate to the fact that this skull came from a secondary deposit. This implies that the cranium and other bones were curated and perhaps processed in some way before their final deposition.

The cave at Annagh was clearly not intended as a burial place for an entire community. All of the remains belonged to adult males. At least two of these were old men. In most traditional communities, an individual’s status in society increases with advanced age, as he or she becomes a repository of the accumulated knowledge and experiences of the group. It seems not unreasonable to expect that battle-scarred old men such as these may have been highly regarded in life and may have merited exceptional treatment in death. If this was the case, the cave at Annagh may have been a specialised locus in the treatment of the dead, perhaps the resting place of a community’s heroes, or maybe just a space reserved for old men.

5. Parish of Abington, barony of Owneybeg. OS 6in. sheet 006. SMR LI006-079——. IGR 169169 158194.

6. Almost all of these could be accounted for as blocks of limestone that had fallen onto the floor of the cave. Large quantities of snail shells were found throughout the cave fill.

7. The animal bone was identified to species and listed by Mary Corkery, Dept of Archaeology, University College Cork, but there is no detailed report available. The list includes bear, boar, dog, hare and sheep, together with unidentifiable large and small mammal remains.

8. NMI 92E47:7:1–7 and 92E47:17.1–3 (sherds); 92E47:17:1 was found beneath burial 1, 92E47:17:2 was found on the ledge above the burial, and 92E47:17:3 was found underneath burial 1 in loose soil.

9. Sherds of this bowl were found in various parts of the cave, in the vicinity of burials 2 and 4. NMI 92E47:18.

10. The second part of the toggle was recovered during post-excavation sieving of samples.

11. NMI 92E47:8.1 and 92E47:8.8 respectively.

12. The flint artefacts have all developed a white chalky patination from the lime-rich environment in the cave.

13. Index of severity of vertebral osteophytic lipping as defined by Wells (1982), which is expressed as D x 100/V where D is the total number of degrees of osteophytosis scored by the vertebral column on a scale of 0–3 and V is the number of hemivertebrae affected by the condition.