1988:089 - BALLYKEEL SOUTH, CO. CLARE, Clare

County: Clare

Site name: BALLYKEEL SOUTH, CO. CLARE

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR CL009-090001

Licence number: E1042

Author: MARY CAHILL

Author/Organisation Address: —

Site type: Iron Age and early medieval graves, c. 300 BCc. AD 1200

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 518011m, N 694481m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 52.994782, -9.221308

Introduction

In June 1988 a burial in a lintel grave was discovered during ground disturbance works at a farm near Kilfenora, Co. Clare. The grave was discovered when a large slab was moved, revealing a long cist containing an inhumation. Mr Fachtna Mellett, the landowner and finder, reported the find to the Garda Síochána at Lisdoonvarna, who informed the NMI. The site was investigated over two days by Mary Cahill, assisted by Paul Mullarkey. The human remains from the site were analysed by Barra Ó Donnabháin.

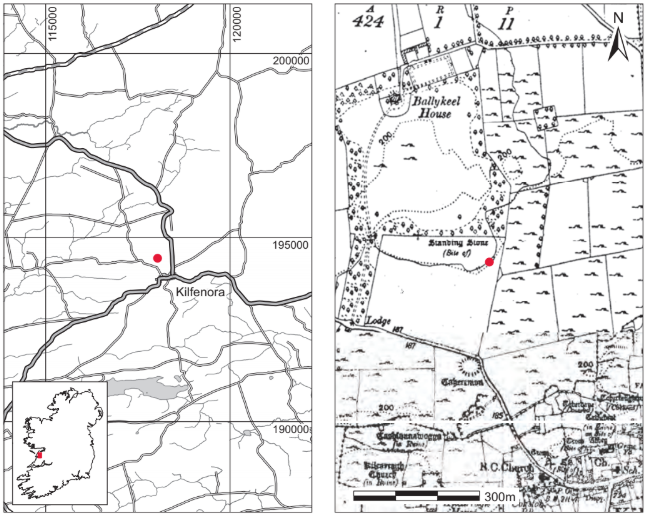

Location (Fig. 4.1)

The site was in the townland of Ballykeel South, north-west Co. Clare.8 It was at an altitude of approximately 60m above sea level, approximately 500m north-west of the village of Kilfenora and less than 1km north-west of the twelfth-century high cross there.

Description of site

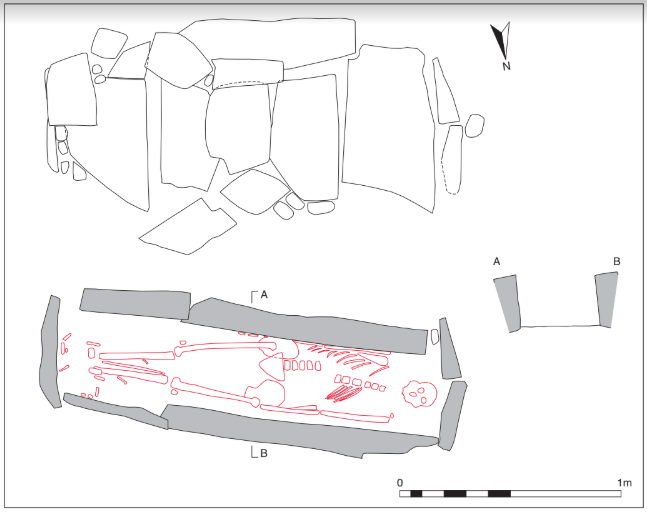

The cist was rectangular in plan, with its long axis aligned roughly west/east. Internally it measured 1.75m long by 0.4m wide by 0.25m high (Fig. 4.2). It was constructed of limestone slabs, two each at the north and south sides, one at the east end and two at the west. Each of the cist sides was formed of one long stone and one short, the maximum length of the longer being 1.25m. The long stones were placed opposite each other, giving the impression of symmetry between the walls. The maximum thickness of the side stones was 0.13m. The cist was covered with six well-fitted lintels, with maximum dimensions of 0.75m by 0.4m.

Two of the slabs overlapped slightly. A number of stones were also placed leaning against the lintels at the north, south and east sides of the cist. These were first thought to be side stones but when removed they were found to be supporting the lintels and not the true side stones of the cist. Two large stones were placed on the north side of the cist and four on the south. A number of smaller packing stones were placed between interstices on both sides. The floor of the cist was not paved.

The cist contained an extended inhumation of an adult male (1988:23) and no accompanying artefacts were found. The skeleton fitted tightly into the cist and was reasonably well preserved. The body lay extended in a supine position with the head to the west and the feet to the east; the arms were extended by the sides. The feet were close together, indicating that the body had probably been wrapped in a winding-sheet or shroud. An unusual pattern of abrasion noticed in the teeth is thought by Ó Donnabháin to be the result of a habitual activity (perhaps industrial) involving passing a narrow object or band of material between the clenched anterior teeth. A sample of the human remains was submitted for radiocarbon dating and yielded a date of 1625 ± 35 BP, which calibrates to 345–539.9

Comment

The grave was interpreted by the excavator as a typical lintel grave and the radiocarbon date for the burial indicates a date between the fourth and sixth centuries, somewhat earlier than the date range normally suggested for lintel graves in Ireland (Fanning 1981, 152; Manning 1986, 166; O’Brien 2003, 67). There is no evidence to suggest that there was more than one grave at this site.

HUMAN REMAINS

BARRA Ó DONNABHÁIN

Introduction

The remains (1988:23) are those of an adult who was probably a young or early middle-aged male. The skeleton was virtually complete and was reasonably well preserved.

Age, sex and stature

Despite the presence of a relatively wide greater sciatic notch, the form of the mastoid processes and the supraorbital ridges, along with the general rugosity of the remains, suggest that this was probably a male. According to the regression formulae developed by Trotter and Gleser (1952; 1958) for the estimation of stature, this individual had a maximum living height of about 169cm (5ft 6in.–5ft 7in.).

The state of fusion of the endocranial sutures suggests that this individual was a middleaged or older adult at the time of death. There is considerable variation in the rates at which the sutures close, so this is stated with considerable diffidence. The estimate of age obtained from the sutures contrasts with the presence of epiphyseal lines, which suggest a younger age. Similarly, the degree of molar wear is not heavy and supports the younger estimate. Considering these factors and both the distribution and severity of age-related degenerative changes, an age at death of between 25 and 35 years seems most likely.

Teeth

All of the permanent teeth had erupted and were in occlusion by the time of death. Mild to moderate deposits of calculus occur on all of the teeth. There was no evidence of caries. Bands of linear enamel hypoplasia occur on each of the canines and are indicative of some systemic disturbance occurring in early childhood (probably between three and five years of age). The alveolar bone indicates the occurrence of periodontitis.

The teeth are worn in a peculiar manner. The anterior dentition has been worn to such a degree that the upper and lower central incisors are mere rounded stumps with little or none of the enamel remaining. This is in stark contrast with the molars, which are only slightly worn with most of this wear confined to the enamel. Secondary dentine has been exposed on all of the first and second molars but all of the molar occlusal surfaces retain some enamel.

Among the anterior teeth, wear is heaviest mesially on the central incisors and is progressively less pronounced on the lateral incisors, canines and premolars. Both upper and lower incisors are worn in an uneven manner, with the wear being greatest on the lingual sides of the teeth. It would not be possible to produce such a pattern of wear through tooth-on-tooth attrition. The marked wear on these anterior teeth must be the product of abrasion. The direction of wear and its concentration on the lingual surfaces are suggestive of an object being repeatedly pulled through the clenched teeth. The uneven distribution of wear and its severity in the region of the central and lateral incisors suggest that a relatively narrow object—maybe 1–3cm wide at most—was involved. The abraded surfaces are smooth and polished. No striations are visible on macroscopic examination of the teeth. It was not possible to examine the dental microwear directly as this would have involved the removal of teeth from the supporting bone. Moulds of the teeth were made and examined under electron microscope in the Department of Zoology at the University of Chicago. This was not successful as the moulding did not yield casts of a sufficiently high resolution to allow clear detection of microwear patterns.

Pathology

This individual suffered from degenerative joint disease (DJD) in the vertebral column and in many of the joints of the left arm and forearm. In the spinal column, the most severe changes were in the neck and lumbar region. The posterior joints of all the cervical vertebrae and the dens of the axis have changes indicative of severe osteoarthritis. DJD in the posterior joints of the second and third cervical elements is so severe that the bones are fused at these joints. The centra of the cervical vertebrae and the posterior joints of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae do not have degenerative changes, although the centra of the sixth to the eleventh thoracics and the second to fifth lumbars have vertebral osteophytosis. This degenerative change is mild (osteophytes projecting <3mm) on T6 to T9, moderate (osteophytes projecting 3–6mm) on T10 and T11, and severe (projecting >6mm) on L2 to L5. The centra of T12, L1 and L4 were not recovered. A single Schmorl’s node—the result of a herniation of the gelatinous core of the invertebral disc—occurs on the superior surface of T9.

In the left arm, mild osteophytic lipping occurs on the distal end of the humerus and also on the proximal end of the ulna. Mild arthritic lipping also occurs on the left trapezium and the articulating proximal end of the first metacarpal. Mild lipping was also evident on six distal hand phalanges.

Of the thirteen costo-vertebral joints available for inspection, ten were arthritic. Only four of the seventeen costo-transverse joints observable had evidence of osteoarthritis.

Discussion

This was probably a younger or early middle-aged male. The distribution of enamel hypoplasia in his teeth may record the occurrence of a systemic childhood illness or it may reflect late weaning. The occurrence of dental calculus and the evidence for periodontal disease suggest poor standards of dental hygiene. This is not unusual among pre-industrial populations. The absence of dental caries reflects a diet low in sugars.

The unusual pattern of abrasion observed in the teeth must have been produced by a habitual activity that involved pulling a narrow object or band of material between the clenched anterior teeth. This may have been part of some industrial activity. Severe degrees of dental abrasion have been observed by ethnographers in Inuit (Eskimo) populations among individuals who used their teeth to soften leather by chewing and biting it (Merbs 1983), but the distribution and nature of abrasion produced by that activity is different from that observed in this individual. The chewing of skins to soften them results in the abrasion of a more extensive area of the dental arcade. It produces flattened occlusal surfaces that are chipped along their margins. In this individual, the wear is unevenly distributed and is concentrated on the central incisors. The margins of the abraded teeth are rounded and worn smooth. This would seem to exclude leather as a causative agent and would suggest that the material involved must have been something softer that was capable of polishing the abraded surfaces.

It is likely that arthritic conditions of the neck, elbow and hand are related to this habitual activity. In the neck, the involvement of the posterior joints and not the centra suggests that rotational rather than compressive forces were at work. The material or object that was pulled through the clenched teeth must have been held in the left hand. The action probably involved a jerking motion of the neck, hand and elbow as the object was pulled out of the mouth. This must have involved some force as it resulted in repeated strains at these joints. The dental abrasion and the degenerative changes indicate that the same action was carried out habitually, probably over a period of years.

The degenerative changes seen in the lower back of this individual are probably not related to the dental abrasion pattern. The vertebral osteophytosis evident in the lower half of the thoracic centra and in all of the observable lumbar centra is probably the result of compressive forces producing degeneration of the intervertebral disc. The paucity of Schmorl’s nodes suggests that these forces were applied in adulthood and not during childhood and adolescence. This type of damage is usually the result of lifting heavy weights and engaging in tough physical labour.

In conclusion, it could be argued that this individual did not belong to an idle élite but rather was perhaps engaged in a specialised trade. He was no stranger to physical labour but spent much of his time in an occupation that regularly involved dragging a narrow band of a relatively soft material between his clenched front teeth. The action was repeated often enough to produce pronounced, localised dental abrasion and recurrent strains in his neck, left elbow and in the left hand. It seems unlikely that this was the result of some leisure pursuit and an as yet unidentified industrial craft activity seems the most plausible explanation.

8. Parish of Kilfenora, barony of Corcomroe. SMR CL009-090001-. IGR 118043 194446.

9. GrN-18567.