County: Cork Site name: LISDUGGAN NORTH, CO. CORK

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR CO023-293 Licence number: 93E175

Author: MARY CAHILL AND ANNA L. BRINDLEY

Site type: Neolithic graves

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 543209m, N 603153m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 46.488181, -15.817314

Introduction

The discovery of two skeletons and two ‘pots’ in a quarry near Kanturk, Co. Cork, was reported to the NMI by Mr M.J. Bowman of Percival Street, Kanturk, Co. Cork, in June 1946. The burial had been uncovered about a month before while a quarry was being prepared for blasting. Mr Bowman wrote to the then Acting Keeper of Irish Antiquities, Dr Joseph Raftery. It is worth quoting from Mr Bowman’s letter, dated 21 June 1946:

During the work they found two skeletons and two ‘pots’. I went this evening to see the site but the skeletons had been removed and the urns broken. Mr Owen Bourke, Assolas, Kanturk, found three pieces of the urns. I enclose a rubbing of two of them. There was no ornamentation on the third piece. I intend to go as soon as possible to see the workmen. I shall send you tomorrow some bones I brought from the site.

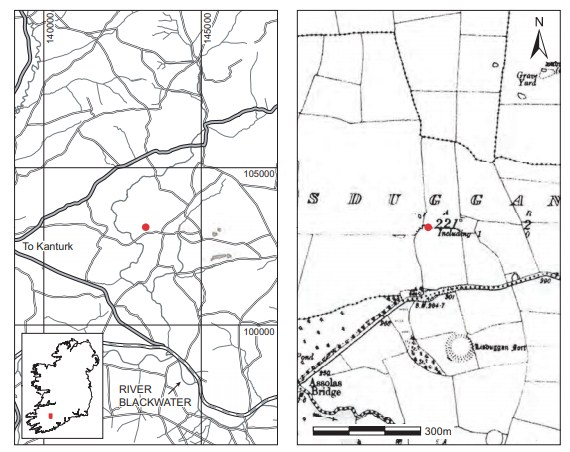

Location (Fig. 2.1)

Unfortunately very little is known of the site. It is located in the townland of Lisduggan North, at approximately 91m OD, overlooking the Awbeg River in an area which has been quarried for limestone for a long time.2 It consists of a limestone cliff, now completely overgrown. Two visits have failed to locate any trace of the original burial site. This may be due to the blasting of the site. In any case, in its present condition, the extent of vegetation cover makes a thorough examination of the cliff face impossible. There is no information available to indicate the depth at which the discovery was made. It is not known how the burial was protected, or the disposition of the two skeletons or of the vessel (or vessels). It is unlikely that a cist could have been constructed in an area where the bedrock lay very close to the surface. It is far more likely that a natural feature such as a cavity in the rock was utilised in the same way as at the County Limerick sites such as Rockbarton (Cahirguillamore; Hunt 1967), Annagh (Ó Floinn 1992a and below) or Killuragh (Woodman, forthcoming). It is unfortunate that details on these points are not available. Whatever the exact circumstances of the burial may have been, it is clear that two inhumations accompanied by a round-based, closed-mouth, shouldered vessel of Neolithic type and closely related to those discussed by Herity (1982, 294–302) were recovered from a site in north Cork, thus extending the known distribution and marking the most southerly extent of this type of pottery.

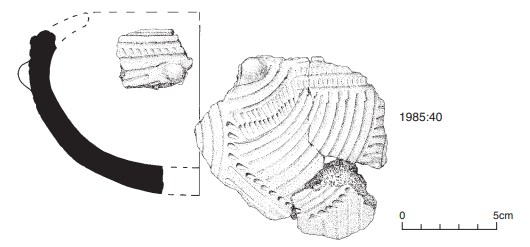

Pottery (Fig. 2.2)

Shouldered vessel 1985:40

Two vessels are reported to have been found with two skeletons. Four sherds, all bearing decoration and from the same vessel, are extant. An undecorated sherd is also mentioned in the correspondence but so far it has not been possible to locate it. It is suggested that this sherd must have come from the second vessel, which may have been plain. Undecorated vessels are sometimes found with the highly decorated pottery which is common to these burials, e.g. Annagh, Co. Limerick (below, pp 17–47). Three of the four remaining sherds can be reassembled and it is possible to give a reasonably detailed description of the vessel and its decorative scheme. The ware is fairly fine, well baked and finished. The exterior is grey-brown in colour, the interior a light brown. Fairly large quartz grits are present and the whole surface is flecked with mica (see report below). The sherds form part of a round-based, closed-mouth, shouldered vessel with all-over decoration. Two rounded bosses are also present. Three sherds form part of the body of the pot below the bosses. The fourth sherd represents a fragment of the pot above, including the bosses, the shoulder and a small portion of the neck. It has been broken off at the point where the neck joined the shoulder. The only element of the decoration of the shoulder that can now be determined is a very slight raised line running circumferentially. The shoulder is marked by a rounded moulding. Four grooves run horizontally; three are interrupted by a rounded boss. The uppermost raised line is scored by oblique strokes. The decoration on the body of the pot consists of panels of curved grooves separated from one another by stabbed lines. The surviving boss is also surrounded by curved grooves. It is separated from the main surviving panel of grooving by a double curved row of irregular stabbed lines. As the grooved area rises towards the upper part of the vessel it is bordered by two horizontal grooves. The two raised lines between the grooves have been lightly scored or milled. Small sections of three other grooved areas survive towards the edges. A very distinct erosion of the surface is visible on the extant lower part of the pot as it curves towards the base. This suggests that the pot may have lain on the ground slightly to one side. The original measurements of the pot have been estimated as follows: max. D c. 18cm; D at shoulder c. 12cm; H c. 9.2cm; max. T of body 1.3cm. The pottery was examined by the late Dr John S. Jackson. Based on the examination of the grits, which consist largely of mica and quartz, the report concludes that the material required to make the vessel could not have been found in the locality and that it must have been sourced in the Leinster Granite area and imported into north Cork.

Comment

The Lisduggan North burial is one of a group distributed in southern Leinster and Munster and for which the term ‘Linkardstown-type burials’ has been proposed (Brindley and Lanting 1990, 1, 6). The salient characteristics are the construction of a sub-megalithic grave and mound or the use or adaptation of a natural cave or feature; the burial of one or several individuals; the deposition of one highly decorated vessel (or occasionally more than one); and the occasional deposition of barbell-shaped bone objects, pins and beads. A series of these graves have been dated, and the development and dating of the associated pottery have also been discussed in some detail (Brindley and Lanting 1990, 5–6 and fig. 2). The typological trend shows a movement from vessels with a shoulder gently rising to the mouth, and with grooved, impressed or stabbed ornament in an asymmetrical arrangement but including zigzag lines and triangular areas either with contrasting fills or left blank (e.g. Ardcrony, Co. Tipperary, and Ballintruer More, Co. Wicklow), to vessels with a flatter shoulder and the increased use of applied or augmented features (lugs, bosses, shoulder tip, mouth opening, such as Drimnagh, Co. Dublin, and Martinstown, Co. Meath), towards vessels with a flat shoulder, reduced use of added or raised features and no use of zigzag/triangle-based motifs (such as Jerpoint West, Co. Kilkenny, and Baunogenasraid, Co. Carlow). Illustrations for all the relevant sites can be seen in the corpus of decorated Neolithic pottery published by Herity (1982). The Lisduggan North bowl can be placed in the second half of this sequence at the overlap of the second and third stages. On these grounds an actual date of c. 3450 BC can be proposed for the grave as a whole. This date is well within the one standard deviation range of the radiocarbon date for Lisduggan North.

HUMAN REMAINS

C.A. ERSKINE

Collection comprises five pieces of skeleton of adult male. One large fragment of body of mandible with well-marked genial tubercles; one lower right canine showing marked wear. One piece of scapula; two pieces of femur and one of tibia show mineralisation. The femoral pieces show an unusually thick cortical structure.

NOTE ON THE GEOLOGY OF THE IMMEDIATE AREA

JOHN S. JACKSON

The site lies on the south flank of Knocknanuss Hill, which is built up of a pile of volcanic ash and fine tuff with subordinate basalt, all of Lower Carboniferous age. In geological literature these rocks are referred to as the Kanturk Volcanics. Recently (about 1960) an eastern extension of these rocks was proved during major quarrying at Ballygiblin (OS 6in. Cork 24), immediately west of ‘High Wood’. The Kanturk Volcanics are overlain by Lower Carboniferous limestone, often with bands of black chert, and on the east flank are underlain by reef limestone (Waulsortian facies) at Subulter, which is almost totally altered to dolomitic limestone. None of these rocks would be rich in mica or quartz, two constituents which are common as ‘grog’4 in the sherds.

Constituents noted in the sherds

The four sherds are referred to as (a) rim fragment, (b) base fragment, (c) large body fragment, (d) small body fragment.

(a) Rim sherd:

Several idiomorphic crystals of felspar occur. They are rectangular in shape, up to 2.5mm in length by about 0.7mm across, and the exposed surface appears to correspond to a cleavage plane. There is one pit, which is a mould from which a felspar crystal has fallen out. Flakes of white mica (muscovite) are common: quartz fragments occur and are water-worn pebbles (about 3mm in diameter).

(b) Base fragment:

Quartz fragments are very common, usually quite small and often less than 1mm in diameter. Some are hypidiomorphic crystals of quartz, exhibiting prism faces and pyramid. One fragment appears to be of fine-grained granite, with quartz and felspar.

(c) Large body fragment:

Possibly the most important ‘grog’ fragment in this sherd is the large fragment beside the major crack. It appears to be of fine-textured granite and contains quartz, felspar and biotite mica (black mica). There is at least one other fragment which also appears to be granite. Quartz fragments are common, usually of the translucent milky variety but some transparent rock-crystal also occurs. Idiomorphic crystals of felspar are present and one is clearly kaolinised.

(d) Small body fragment:

One fragment occurs which is possibly aplite, a rather fine-textured variety of granite. Quartz is common as a constituent, sometimes as hypidiomorphic crystals showing parts of prism faces and pyramids. White mica flakes (muscovite) are common.

Conclusion

Most of the ‘grog’ constituents are water-worn pebbles of small size. Derivation from a granite source is consistent with the variety of materials, i.e. quartz, felspar and mica. The three fragments of aplite or fine-grained granite are also consistent with alluvial material derived from a granite area. Conversely, I have not found fragments which would be local in origin, i.e. fragments of basalt or volcanic ash, chert from the limestone, sandstone (from the local Millstone Grit), etc. Therefore the bulk of the evidence available suggests that the pot was made in, or close to, a granite area and ‘imported’ into north Cork. The closest granites to Kanturk are the Leinster granite on the east and the Galway granite on the north. Erratics of Galway granite are not uncommon in the Mallow–Kanturk area but it is improbable that they would have been sufficiently abundant to produce alluvial gravels from which the ‘grog’ was derived.

2. Parish of Castlemagner, barony of Duhallow. OS 6in. sheet 23. SMR CO023-293——. IGR 143247 103098.

3. OxA-2681.

4. The term ‘grog’ used by Dr Jackson more correctly applies to crushed pottery used as temper. Dr Jackson is referring in his report to natural inclusions in the clay body.