County: Galway Site name: CARROWNTOBER EAST, CO. GALWAY

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR GA084-045 Licence number: E1071

Author: ADOLF MAHR

Site type: Early Bronze Age graves

Period/Dating: —

ITM: E 552361m, N 730427m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.321967, -8.715039

Introduction

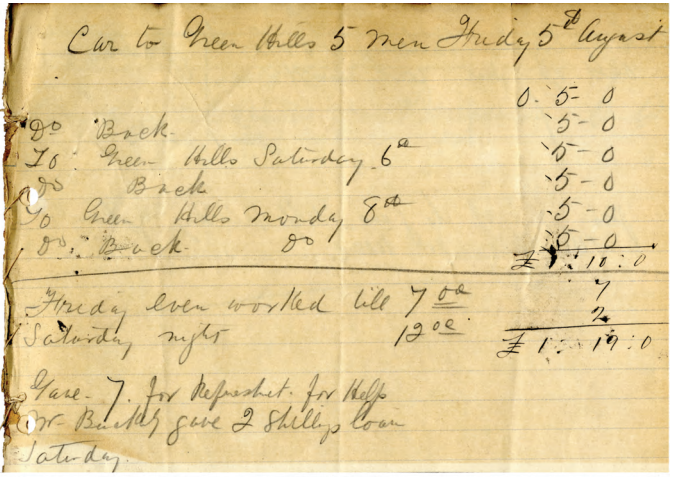

In April 1931 a short cist containing an inhumation and a vase was discovered during digging in a sandpit near Athenry, Co. Galway. The find was immediately reported to the Garda Síochána at Athenry, who visited the site and sealed the cist. The site was also visited by Dr T.B. Costello, local antiquarian and collector, who removed the vase and gave it to the Gardaí for safekeeping. The Gardaí then informed the NMI by telegraph (Pl. 29). The site, on the land of Mr J. Bourke, was investigated on the following day, 16 April 1931, by Adolf Mahr. This report is based on Mahr’s notes, sketches and photographs.

Location(Fig. 3.72)

The site was in the townland of Carrowntober East, 3km north-east of Athenry, Co. Galway.110 The burial was at the top of an esker ridge close to the 50m contour (Pl. 30).

Description of site

The burial was found at a depth of 0.9m below ground level (Pl. 31). The cist was rectangular in plan, with its long axis aligned north-east/south-west. Externally it measured 1.08m long by 0.6m wide by 0.48m high.111 It was composed of five limestone slabs set on edge, with one each forming the northern, eastern and southern walls and two thin slabs placed parallel at the western wall. These slabs were regular in form, the maximum thickness being 0.15m. The eastern slab was shorter than the rest and two stones measuring 0.1m in height had been

placed on it to compensate for the height difference. There is no evidence in Mahr’s sketches for packing stones around the cist. The cist was sealed by a ‘very carefully dressed’ capstone measuring 1.2m by 0.6m. The floor of the cist was not paved but consisted of undisturbed gravel. It is possible that the pit containing the cist had already been destroyed during the quarrying operations. The cist contained a crouched articulated burial of an adolescent female, and a cremation representing an adult female and an adolescent (1931:167.1–3).112 The burials were accompanied by an inverted vase and two flint scrapers. The inhumation burial lay on its right side with the head to the south-west, facing the southern wall of the cist. The arms and legs appear to have been flexed, with the arms placed in front of the body. Mahr’s report states that there were many bone splinters and some larger bones (possibly animal bones) in the upper fill of the cist. Some of the bones were stained green, according to the excavator, from ‘decomposited [sic] bronze’. Two flint scrapers were found at the centre of the cist, near the long bones. The vase was complete and inverted when found and was placed to the north of the skull, near the north-western corner of the cist. The vessel has been classified as a bipartite vase (Ó Ríordáin and Waddell 1993, 263).

Bipartite vase, 1931:166(Fig. 3.73; Pl. 32)

The vessel has four imperforate lugs or stops and bears an overall decorative pattern of incised lines in horizontal rows arranged in a herringbone pattern. The shoulder groove is also decorated with herringbone incisions. The rim, which is internally bevelled, has a herringbone pattern on the inside, while the top of the rim is decorated with incised lines. The base is plain. Dimensions: H 12.4cm; D ext. rim 12.6cm; D base 5cm.

Two flint scrapers, 1931:168.1–2(Fig. 3.73)

Two flint flake convex end scrapers were found in the cist (Woodman et al. 2006, 156–7). The scraper numbered 1931:168.1 has maximum dimensions as follows: L 3.2cm; W 3.46cm; T 1.73cm. Scraper no. 1931:168.2 has maximum dimensions as follows: L 3.35cm; W 3.64cm; T 1.15cm.

Comment

In 1929, also in the townland of Carrowntober (reported as Curratober), a short rectangular cist was discovered in a sandpit (Waddell 1990, 92; Anon. 1929). It contained the unburnt bones of a child and a fragmentary bipartite vase. There are two townlands, Carrowntober East and Carrowntober West, noted on OS 6in. sheet 84. Sandpits are shown on the 1919 edition on both sides of a road running east/west across the southern portion of the townland but not in any other part of the townland. The site discovered in 1929 is described as being situated ‘at the top of the pit’ and it is stated that the sandpit had been made in a ‘mound . . . [which is] one of a chain of mounds forming an esker’. It seems highly likely that both cists were found in the same area, although no comment is made in the 1931 report on the previous discovery. As however, the finds were taken into the care of University College, Galway, rather than the NMI, the link may not have been made at the time. The vase from the cist burial discovered in 1931 is remarkably similar to a vase (NMI 1913:45; Ó Ríordáin and Waddell 1993, 100, 265, fig. 521) discovered at Gortnahown, Co. Galway (OS 6in. sheet 84; about 1.5km south-west of the site under discussion), in terms of their closely comparable decorative schemes consisting solely of horizontal herringbone patterns, the occurrence of imperforate lugs, the decoration on the internal rim bevel and the form of the vessels. Ó Ríordáin and Waddell (1993, 43) refer to the vase from Carrowntober in discussing the similarity between Yorkshire vases and some Irish vases but, while mentioning the general similarities between vessels from both areas, they ultimately see the similarities as ‘two broadly contemporary pottery traditions . . . both sharing an ultimate common heritage of either late Neolithic or beaker ceramic traditions or both’. Similarities between vessels from the same location or from sites at a considerable distance from one another are not unknown and have been discussed in both the Irish and British contexts (Sheridan 1993, 51–65, fig. 18). The herringbone motif is one of the most popular and its distribution is widespread (ibid., 54, fig. 18). The very close similarity between the two vessels discussed here seems much more than could occur by coincidence, and the idea that both vessels came from the same potter’s hand must be considered. The radiocarbon date obtained from the unburnt bones was 3755±30 BP, which calibrates to 2285–2040 BC113 at 95.4% probability, while the AMS date for carbonate from the cremation was 3670±40 BP, which calibrates to 2195–1939 BC at 95.4% probability114 Brindley (2007, 255–6) interprets these two dates as suggesting that, although the vase from Carrowntober East and a vase from Moyveela, Co. Galway, have produced the earliest dates for vases, i.e. 3755±30 BP, the two dates from Carrowntober East overlap ‘in the decades around 2100 BC’. She regards the younger date as being more likely to be correct in terms of the true date of the burial, as both vessels are similar to a series of vases with dates after 3680±50 BP. The Carrowntober East vase is therefore placed by Brindley (2007, 257) within stage 1 of the development of vases, which is dated to the period 2020/1990–1920 BC.

HUMAN REMAINS

LAUREEN BUCKLEY

Introduction

This short cist was discovered during digging in a sandpit in 1931. The burial was that of a female adolescent and it lay on its right side with the head to the south-west, facing south. The burial was in good condition and was virtually complete. Mahr describes a number of bone splinters and possible animal bones that were present in the upper fill of the cist. He also refers to a portion of child’s skull found near the northern side of the cist. These, in fact, are all cremated bones and are described separately below, under the label 1931:167.3[C].

Inhumation: adolescent female (1931:167.1–2)

The skull had been removed prior to excavation and was labelled 1931:167A; the remainder of the bones were subsequently labelled 1931:167B [both renumbered 1931:167.1–2]. In fact, they all belong to the one individual. The skull was virtually complete, with the frontal, parietal, temporal, sphenoid and occipital bones all complete and in one piece. The facial bones were in poor condition, with only the left zygomatic, right side of the maxilla and part of the left maxilla present. Although the anterior part of the mandible was damaged it was virtually complete.

The vertebral column consisted of all the cervical vertebrae (with the upper three being complete), six thoracic vertebral arches and all of the lumbar vertebrae (with the lower four being complete). There were five ribs from the left side and ten from the right, and the manubrium and part of the body of the sternum were also present. Both scapulae and clavicles were present but incomplete and all the arm bones were present and complete, apart from the proximal third of the left radius and distal third of the right ulna. The scaphoid, capitate and lunate, all the metacarpals and four proximal phalanges were present from the left hand. All the carpals apart from the pisiform, all the metacarpals apart from the fifth and three proximal, three middle and one distal hand phalanges remained from the right hand. The pelvis consisted of a complete left ilium, ischium and pubic bone fully fused at the acetabulum, an almost complete right ilium and right ischium, a complete right pubis and a virtually complete sacrum. All the leg bones were virtually complete, apart from the left patella, which was missing. The original tibiae, however, had been used for radiocarbon dating and replaced with resin replicas. The foot bones consisted of the left and right talus, calcaneum, cuboid, navicular and first cuneiforms. All the metatarsals were present and there were three proximal phalanges from the right foot.

Age and sex

The broad sub-pubic angle, ventral arc and sub-pubic concavity all indicated that this was a female skeleton. Some features of the skull, the external occipital protuberance, the shape of the orbits and supraorbital ridges, were also indicative of a female. These are not as reliable as the pubic bones, however, and as the individual was an adolescent the skull was probably not fully developed. Since the three bones of the innominate had fused fully, the pelvis had probably fully developed the characteristics that enabled it to be sexed. As the pubic bone is generally more reliable than any other bone in determining sex, it is safe to conclude that this was a female individual. Fusion of the three bones of the pelvis occurs between ten and sixteen years in females. The head of the femur was also fused and this occurs between the ages of fourteen and sixteen in females. Some other epiphyses, including a head of a metatarsal and the base of a first metatarsal, were fused, also indicating that the individual was over fourteen years but probably less than eighteen years of age at the time of death. The crown of the third molar was complete and this usually occurs around fourteen years of age. Some of the root was formed but it was not possible to see how well developed it was. As root development is usually complete by eighteen years, however, it can be stated that the individual was aged between fourteen and eighteen years at the time of death.

Dentition

Anomalies: there was a small socket, possibly for the deciduous canine, in the left side of the mandible. As the permanent canine was erupted, this suggests retention of the deciduous canine. The lower left second permanent molar had erupted at an angle in the jaw. It was inclined at a 45° angle towards the lingual side of the mandible.

Attrition: there was no wear visible on any of the teeth that were present.

Calculus: as most of the teeth surfaces were covered with a mineral concretion, it was difficult to assess the degree of calculus deposits. Slight deposits were, however, noted on the lingual surfaces of the upper and lower premolars on the left side of the jaw and on the buccal surface of the upper right second premolar.

Skeletal pathology

No skeletal pathology was noted on the bones. A number of bones, particularly the arm bones and ribs, had a deposit of mineral concretion on them but it was still possible to examine most of the bone surfaces for lesions.

Summary

This was the almost complete skeleton of an adolescent female, aged 14–18 years at the time of death. No pathology was noted on the bones and the teeth were in good condition, with little wear or calculus deposits present. There were some anomalies in the dentition, however, with a deciduous canine being retained in the left side of the mandible and eruption of the left second molar at an angle in the mandible.

Cremation (1931:167.3)

It was difficult to describe the colour of this cremation as many bones were encrusted with mineral deposits, giving them an orangey/brown colour. The underlying colour, however, seems to be white/grey. The bone seems to be efficiently cremated and there is much horizontal fissuring and severe distortion of the bone. A total of 482 fragments weighing 1,045g were present. The fragmentation of the sample is presented in Table 3.32, with the largest fragment measuring 114mm.

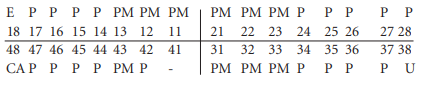

[caption id="attachment_45813" align="aligncenter" width="552"] Table 3.32—Fragmentation of bone, 1931:167.3.[/caption]

Table 3.32—Fragmentation of bone, 1931:167.3.[/caption]

It can be seen that over half the sample consists of very large fragments, and that almost all the sample is made up of large fragments more than 15mm in length. Most of the smaller fragments probably came from post-excavation fragmentation of the bone. It is highly likely, however, that smaller fragments were not collected at the time of excavation. Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to assume that the bone was not deliberately crushed after collection from the funeral pyre.

Identifiable bone

Table 3.41—Proportion of identified bone, 1956:215.

Table 3.34—Summary of identified bone, 1931:167.3.

Table 3.34 summarises the main parts of the skeleton identified from this sample. It can be seen that the proportion of skull bones is twice what would be expected in a normal cremation. This usually happens when there is more than one individual in a cremation, as the skull bones are more easily identified than fragmented long bone. The amount of axial skeleton is much less than it should be. This is because when small fragments are not collected much of the axial skeleton is underrepresented. The quantity of upper and lower limb bones is only slightly less than normally found in a cremation.

Skull

There were large fragments of parietal bone with unfused sagittal suture. The posterior part of the left parietal bone with the lambdoid and squamosal suture visible was also present. There was also a fragment of the posterior part of the right parietal bone. There was a fragment of occipital bone with lambda present. There were three other fragments of occipital bone, with some of the nuchal crest visible. The right side of a frontal bone with the metopic suture and part of the orbit was present. Its maximum thickness was 4mm. The left side of a frontal and the left orbit were also present. The left temporal fossa was present and there was another left temporal fossa with part of the squamous temporal bone and the zygomatic arch present. A right temporal fossa and zygomatic arch was also present. There were two right and one left petrous portions of the temporal bone, as well as the squamous part of a right temporal bone. The right zygomatic bone was present. From the thickness of the parietal bone there seemed to be one adult and one juvenile skull present.

Mandible

There was a large section of the left side of the mandible near the angle with part of the ramus and a socket for the last molar. There was also a portion of the right side from near the internal angle, also with the socket for the last molar. There was an additional fragment from another mandible, also from the left side near the angle with a socket for the last molar. This fragment was smaller than the other mandible. Two fragments of the body and one left condyle were also present but there were no tooth fragments.

Vertebrae

The neural arches of the first and second cervical vertebrae were present and there was one fragment of body and one fragment of arch from the lower cervical vertebrae. One upper thoracic body and one lower thoracic body were present and there were at least three arches. The epiphyses of the bodies had just fused. There was one complete lumbar body and fragments of two others, as well as two lumbar arches.

Ribs

There were at least six left and three right ribs present. Most of the fragments were from the shaft, but some were from near the angles.

Pelvis

There was one large section of left ilium from a female, with the auricular surface present. There were other fragments of ilium with the iliac crest unfused. One ischium and one unfused ischial epiphysis were present. There was only one fragment of acetabulum. The body of the first sacral vertebra was also present.

Clavicle

One almost complete right clavicle and part of the shaft of a left clavicle were present.

Scapulae

The base of an acromion and a coracoid process from a left scapula were present.

Humerus

The proximal half of the shaft of an adult bone was present, as well as the distal third of an adult left humerus. There were several other shaft fragments, one humerus head and fragments of a distal joint surface.

Radius

The proximal half of a shaft, including the proximal joint end, was present. Unfortunately it was so warped that it was not possible to say which side it was from. Another proximal third of radius with the joint end was present. There were fragments of shaft and a distal epiphysis from a right bone.

Ulna

There were fragments of shaft from both the proximal and distal parts of the bone.

Carpals, metacarpals and phalanges

Only one proximal hand phalanx was present.

Femur

There was one very large piece of a right femur, with the neck and a large part of the medial side of the proximal shaft present. This may be from an adolescent as the femur head does not seem to have fused. The proximal shaft and part of the neck from a left femur, probably from the same individual as the right bone, was also present. The left neck and part of the proximal shaft from an adult bone was present, together with a lesser trochanter and large part of the shaft from the same bone. There was also a fragment of greater trochanter. Several large fragments of shaft and some fragments of the proximal joint surfaces were present.

Tibia

All the fragments were of the shaft, including some very large fragments. There were fragments of the posterior surfaces and one fragment of distal joint surface.

Fibula

Fragments of shaft from at least two bones, including a proximal end of shaft. There was also a left distal joint surface.

Patella

One almost complete right patella was present and there was a fragment of one other.

Tarsals/metatarsals

Fragments from one talus and two metatarsal shafts were present.

Minimum number of individuals

There appear to be two individuals present. One seems to be an adult female and one seems to be an adolescent.

Summary and conclusions

This sample represents the efficiently cremated remains of at least two individuals. Over half of the sample consisted of very large fragments, the largest being 114mm in length. The very small proportion of small fragments probably indicates that they were not collected at the time of excavation, as the cremation was not recognised at that time. Nevertheless, the very large fragments suggest that the bone had not been deliberately crushed as part of the cremation ritual. Most skeletal elements were present, although the amount of skull was twice what would be expected from a normal cremation. Although the proportion of skull should be the same no matter how many individuals are present, in practice, because skull is so easy to identify, there is a noticeable increase in the proportion of skull in multiple cremations. In this case two individuals, one an adult female and one an adolescent, were present. There was no pathology observed on the bone.

110. Parish and barony of Athenry, Co. Galway. SMR GA084-045——. IGR 152400 230400.

111. Mahr’s sketch is not to scale and only gives external measurements. It was therefore not possible to obtain the internal measurements of the cist.

112. The cremation was identified in 2002 when examined by osteoarchaeologist Laureen Buckley. The slabs of the cist were also sent to the NMI but do not seem to have been registered.

113. GrN-11354.

114. GrA-24168.