County: Mayo Site name: THE DESERTED VILLAGE, Slievemore (Achill Island)

Sites and Monuments Record No.: SMR 42:00802–42:10914 Licence number: 91E0047

Author: Theresa McDonald, Achill Folklife Centre (Ionad Eolais ar Shaol an Pobáil Acla Teoranta), with artefact report by Elizabeth

Site type: Settlement cluster and Souterrain

Period/Dating: Multi-period

ITM: E 468568m, N 803481m

Latitude, Longitude (decimal degrees): 53.963908, -10.003031

The tenth season of excavations took place at the Deserted Village over eight weeks, from 26 June to 21 August 2000. Two sites were opened this year, House #36 and a souterrain, both in the village of Tuar.

House #36 and garden

Reassessment of the existing data was thought desirable to achieve a greater understanding of the sites, e.g. the close association of the house and garden with the drainage system. The modification of the manure pit, the main drain and the garden walls became major features of interest.

Cutting A was not excavated this year. A few finds (pottery sherds and wood fragments) were found in situ during a clean-back of the area. A large piece of hard wood was found protruding out of the soil and has been left for excavation in 2001.

In Cutting B the garden, the layer prior to the building of the house, was reached. This garden is mainly delimited by two walls: a curved north wall and the southern wall, which separates Cuttings B and C. Both were built after the construction of the house.

The southern wall touches the eastern house wall, without having any obvious connection to it. The north wall must have touched the north gable at one stage, but the wall here had been removed at an unknown period, prior to the excavation. The western wall of the field north of the garden is very well constructed with small stones and follows a straight line to within a few metres of the house garden wall, when it suddenly curves towards it, and from that line on, the construction is very rough and consists of medium to large stones, suggesting a later innovation.

Two apparently parallel trenches in Cutting B, one cutting into F37 and the other into F101, are the only remains that are left from the activity of the pre-house period. They may be the remains of lazy-beds. If that hypothesis is correct, they are probably part of a big field that stretched from north to south in the area where the house now stands.

Trench F18, north of the north gable of House #36, has now been designated Cutting D, as it lies at right angles to both Cuttings A and B. F19, a cut in this trench that is not parallel to the north gable of the house, was originally thought to be a drain, but further examination shows that its orientation corresponds with the orientation of the gables of the surrounding houses. As there is no other obvious cut for House #36 nearby, it is possible that this is the original northern cut of the house. If it is, it seems that the builders changed their minds about the orientation of the house between the time they made the cut and the time they built the walls.

The cut of the test-trench, Cutting D, at the north-east corner of the house, revealed that a vertical cut had been made in layer F37, which has a minimum height of 0.34m. The cut leaves a space 0.8–0.14m between the edge of the cut and the wall. The eastern wall of the house cuts layer F37, which indicates that this layer is earlier than the building.

In Cutting C the cleaning back and the analysis of the southern wall of the manure pit revealed an old pathway, constructed before the building of the manure pit. Activity in this area, before the construction of House #36, is now also being revealed.

The platform south of the house is made of a mixed sandy soil. It exhibits a variation of three different layers, probably due to the manner in which the soil was deposited. South of the eastern wall, the deposited soil elevates the wall by 0.1m from the ground surface. Observation of the exterior of the house indicates that the walls appear to be built directly on top of the platform, even following a bump in the middle of this platform.

From the eastern baulk into the doorway of the house, it seems that the ground is higher inside the house than outside. Most of the stones at the bottom of the wall inside are hidden by the soil. It seems that soil was brought into the house from outside in order to make a floor. A metalled surface partially covers the area, south of the channel, where the cattle were kept. Once the channel was dug, roughly square stones were used to line the bottom, and long rectangular stones were used to form the edges and the top. Then a flagstone floor was placed on top of the earthen base, north of the channel. Those stones are quite well imbricated with the stones of the channel. The fireplace stone is at the same level as the flagstone floor and is a flat round stone made of schist, which exhibits evidence of deep burnmarks. All around it and partially underneath it are medium-sized schist stones (c. 0.1m wide), which also exhibit burnmarks; some of these are broken into two or three pieces. It appears that the fireplace stone was placed on top of those medium-sized stones, so as to isolate the fire from the ground surface.

The layers of topsoil inside the house produced sherds of pottery dating to between c. 1750 and the 1940s. It is surprising that nothing earlier has been found on this site, considering that the Slievemore area was inhabited from the Neolithic period onwards.

The manure pit was built at the same time as the house; the two are inextricably linked, as the drainage channel within the house pours its contents into the manure pit via a metalled surface.

The old roadway was in use before the manure pit was dug, so that when the builders dug the cut of the manure pit they left undisturbed a wall structure on their right, reusing it in order to avoid building a wall east of the pit.

East of this wall is a large pit into which a series of five smaller pits has been dug. These smaller pits are also dug into each other and filled by several different layers of stones, organic soil or sand, filled in several times, with some layers covering two pits. No dating element has been found in them, so it is not known whether they were dug during the same period or several years/decades/centuries separate them. It is not even known whether they are contemporaneous with the building of the curved wall F25, the use of the old pathway, the digging of the drain F47 or the usage of the house, which could have been during the pre-Famine period or the booley phase. They may also have no relation with any of those activities. (See Excavations 1998, 158–9, and Excavations 1999, 230–1).

Immediately south of these pits is a shallow drain filled with small stones, which has been dug into a block of yellow clay. Its western extremity ends on the top of the manure pit, so there is no obvious relationship between them. The drain is sited too high to have been used to drain out the contents of the manure pit, and we cannot see what it could have brought into it. It is difficult to say whether it was related to the curved wall on the north-east, as that wall seems to stop at the junction between the drain and the manure pit. Also, the drain seems to continue the curvature of the wall, although it is straighter. But as the cut of the manure pit is so close it cannot yet be determined whether the drain extended further west or whether the drain and the curved wall are related.

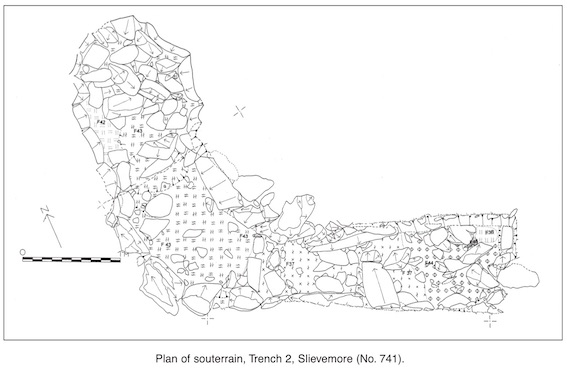

The souterrain

Trench 2/Cutting A: the old roadway

This cutting was excavated in 1998 and extended by 1m in 1999 to reveal the metalled surface of a roadway and a line of medium-sized boulders that appears to delimit its northern edge. Several very large boulders at the eastern end may be the foundation of an earlier structure or may be connected in some way with the partially robbed-out original external west wall of the nearby House #25, which has been extensively remodelled at an unknown period in the past.

Trench 2/Cutting B: the chamber

Approximately 0.6m of fill inside the chamber was removed this season. This soil/fill was deeply stained by manganese. The water still continued to fill the chamber every time it rained.

The fill seems to represent two phases, although it is not certain whether they represent the fill of the 1940s or an earlier fill.

A large number of medium to large stones were removed from the passage. Interestingly, there were very few large stones in the chamber of the souterrain at this level, except for one very large orthostatic stone (0.46m x 0.52m x 0.18m), which lay prostrate, close to the central part of the chamber and south of the ‘chimney’ or ‘air vent’. All of the stones removed from the chamber had burnmarks on them, including the large orthostat.

Trench 2/Cutting C: the passageway

A yellow/orange layer of soil extended from the chamber to the mid-point of the passage, where there is a narrowing of the passage and some slight evidence (fallen stones) that this area may have been partially blocked at some stage. At the probable end of the original passageway the soil changes markedly to a pocket of grey soil and a small lens of red oxidised soil, similar to that found in the chamber of the souterrain. There seems to be a clear demarcation line between this deposit and the soil in the passageway. This area abuts Cutting D, the mound at the southern end of the passage. At this junction, just under the topsoil, a quartz scraper and a fragment of post-medieval pottery were found.

Trench 2/Cutting D: the mound

This mound was originally thought to represent the opening of the souterrain, blocked by local residents in the 1940s. However, the excavation in the passageway indicated that the passageway terminated further to the north, so the purpose of the mound seemed enigmatic. On desodding the mound, a raised area c. 0.75m high was revealed, consisting of fine-grained, brown (Slievemore) soil in which were large to medium-sized stones (c. 0.2m x 0.15m). The soil was heavily compacted and difficult to remove. Approximately midway along the mound was a small recessed area that appeared to be an earlier cut. Because of the difficulty in trowelling the mound, it was decided to section along this cut, F27, for easier investigation. The overlying layer of soil here was quite thick, c. 0.15m deep, and did not extend to the north into the passageway of the souterrain, appearing to be separate from it, although admittedly similar to deposits of soil within the chamber of the souterrain.

After removal of the overlying soil, a pit with a clearly stratified deposit was revealed. This consisted of alternating layers of a dark grey, brown/grey and burnt orange deposit, with charcoal. Several samples of this deposit (F39) were taken and sent to Gronigen for analysis and radiocarbon dating. Preliminary analysis indicates that the burnt deposit consisted of ling (Calluna vulgaris).

Pre-House #36 activity

The village is built along an old road and north of a more recent road. Generally, in linear settlements, when a new house is to be built or an older house extended or restored/renovated, the builder (occupier) has to adjust to the original village layout.

Building between two existing houses would be extremely difficult because the ability to manoeuvre is restricted. This is probably why the thirteen houses built after 1838 were sited west of the existing houses in Tuar. If one applies this philosophy to the village of Tuar, can one also say that House #36, at the extreme eastern end of the village, is later than Houses #14 and #35? The date range of the artefacts from House #36 spans the period from c. 1750 to 1870, with some later artefacts from the booley phase (c. 1880 to 1940).

There is evidence of an old pathway, characterised by a metalled surface, to the west of the house and also to the south-east, under the southern wall of the manure pit. One can still see the emplacement of the old road running between the two houses, north-west of House #36 (Houses #32 and #35), so it is probable that the pathway excavated is a continuation of this old road. In this case the old road would extend from between Houses #32 and #35, continue down the hill between the manure pit of House #35 and the drain P2 and then turn east, following the north gable of House #37.

It is also possible that the original big field extended much closer to House #37, leaving maybe only enough room for the old road to pass between it and House #36, given that the western wall of this (big) field is exactly in line with the western wall of House #37. Even more interesting is that along the west wall of this house is a very deep drain. If the drain of House #37 is the equivalent of the drain P2 of House #36, that drain would be an exact continuation of the original field drain. Also, layer F37/101 in Cutting B represents two trenches, apparently parallel to and following the mountain slope, which may be the remains of lazy-beds that existed before the construction of the house.

It is therefore possible that these are the remains of the bottom end of a large potato field. In addition, the bottom of the western field wall has been destroyed and roughly rebuilt, in order to join the north garden wall to House #36. That joint corresponds with the limit of the excavation and also with the drain P2.

Therefore, until more excavation work takes place, further comment cannot be made on this aspect. However, it does seem that the deep field drain was diverted at the same time as the wall, in order for it to drain into P2.

The last event that took place before the construction of the house was the redeposition of the layer of yellow clay F30 and the wall F25, east of the manure pit. Two things show this to be the sequence of events. The layer of yellow clay corresponds to F29, which lies under the southern wall of the manure pit, and the digging of the manure pit and the walls protecting its edges did not touch wall F25. The function of this feature is unknown. In addition, the possible drain F47, cut into that mass of yellow clay, was obviously there before the manure pit, because, though not related to it, it is cut by it. It might be a transverse drain in the original field, presupposing that this field extended this far to the south.

To summarise, the only real evidence we have at the moment relates to the old pathway under the southern wall of the manure pit, the modification of the bottom of the original field where House #36 now lies and the redeposition of the block of yellow clay F30 and the wall F25.

Conclusion

There are few absolute dates available for the site at present. This will be rectified when the results of the current study of the finds by Elizabeth Davis becomes available, which should provide a precise date for each layer. The site matrix will also be available and will indicate the sequence of events that took place during the construction and occupation of House #36, the period of abandonment and later seasonal reoccupation.

There is already some information on the history of the house, as all the finds in and around it date to the period between c. 1750 and c. 1870, so one can reasonably assume that the house was constructed in around 1750. That means that the old pathway underneath the manure pit pre-dates 1750, as well as the redeposited yellow clay F29/30, the eastern wall of the manure pit F25 and the possible drain F47, and the two dark patches at the bottom of the manure pit F67 and F68. In Cutting B the layers F37/101, cut by the cut of the house, can also be dated to before 1750.

As the house is a classic byre house, it is reasonable to assume that the manure pit is contemporaneous with the house, as well as the drain P2, as these features are directly associated with the occupation and usage of the house. The layers F85, F87 and F77 can probably also be dated to c. 1750, or very soon after, as they sit right on top of F37/101.

The history of the rest of the site depends on whether the garden walls were built at the same time as the house. If that was the case, the modification of the field wall joining the garden to the house dates from around 1750. It also indicates that the field walls on the north and east pre-date 1750.

On the above evidence it seems that House #37 was built before House #36. If this was not the case, there would have been no reason for the old pathway to follow the north gable of House #37. This house seems also to correspond with the original field where House #36 is now sited, so it is this field that is most likely to pre-date the construction of the house in c. 1750.

The finds inside the house date up to the 1940s, which indicates that the house was in use during the booley phase of the village, c. 1880–1940. This was after the abandonment, which occurred between 1851 and 1855. The reoccupation occurred after the redistribution of holdings by the Congested Districts Board and later by the Land Commission.

The artefacts

An interesting range of ceramics has been found during excavations at the Deserted Village of Slievemore. These include creamware, pearware, whiteware, salt-glazed stoneware, mochaware, black-glazed red earthenware, spongeware and English porcelain. The types of ceramic fragments found are generally from tableware, such as cups, plates, bowls etc., and utilitarian objects, such as black-glazed redware jugs and salt-glazed honey/preserve jars. Although our research is incomplete, there seems to be an interesting pattern emerging in the use of crude utilitarian redwares with whitewares. The ceramics from House #36 date to between 1750 and 1868, giving a good indication of when the house was permanently occupied.

A complete analysis of the artefacts from the Deserted Village will be added in May 2000 to the Field School website at: www.achill-fieldschool.com.

Dooagh, Achill, Co. Mayo